T h e C a u s e I s B o r n

I d e a s

I d e a s

I d e a s

Learning

photo caption

Captain Wingate. To a member of the Jewish community he said, "I believe that the very existence of mankind is justified when it is based on the moral foundations of the Bible."30

Photograph courtesy of

Her Majesty's Stationary

Office, U.K.

W ingate was based in Jerusalem as part of the General Headquarters intelligence staff. As intelligence officer he traveled over Palestine gathering information, studying the situation. Wingate studied the tactics of the Arab guerillas who were striking Jews in Palestine and successfully evading British troops. He ventured across northern Palestine to discover Arab arms smuggling routes, including traveling to border areas. He clandestinely observed the movement of rebels and arms crossing the border without being detected. He visited Jewish communities such as kibbutzim and was struck by the activities and accomplishments of the Yishuv. He became deeply impressed by their energy, by their actions to bring prosperity to the land, intrigued by their establishing of distant settlements in strategic locations. He began to take a strong interest in all things Jewish, from developing friendships to trying to learn Hebrew.

photo caption

Sabotaged railway line. In mid-1938, much of the countryside in the northern half of Palestine was falling under temporary rebel influence. They tried to coordinate & command their efforts through the Higher Arab Committee, but were unsuccessful.

Photo courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London

photo caption

British troops searching Arab village for illegal arms. One British colonial official put it, "Our intelligence was haphazard and patchy, and consequently much of our military effort against the rebels was clumsy & misdirected."31

Photo courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London

Respect in him grew for the spiritual actions of the Zionists who were working to fulfill the prophecies of the return of the Jews to the land of Israel. Being in the Holy Land was bringing a special meaning to him, the history which he had grown up with and studied, real and inspirational. "He saw the Bible not as a prayer book, but as a history of a great people who had lived in Palestine & have now returned to the country again."1 Seeing the Jewish community working to persevere in the face of hostility, he declared, "When I came to Palestine, I found a whole people who had been looked down upon and made to feel unwanted for scores of generations, and yet at the end of it, they were undefeated and building their country anew. I felt I belonged to such a people."2 Orde Wingate fell in love with and grew committed to the Zionist goal. He resolved to help the Jews in Palestine fight to defend themselves and fulfill their Zionist dream.

Soon after his arrival in Palestine he began making contacts with the Jewish leadership. He worked to overcome the distrust directed towards him from the hesitant Jewish leadership. A meeting was arranged with Emanuel Wilenski via a sympathetic British officer. Wilenski was the chief intelligence officer of the Haganah in the north. He listended as Wingate told him the Jewish Agency's policy of self-restraint was wrong and that passive defensive measures were impractical now. He was surprised to hear Wingate declare that the Jews were practically in a war and that it was his ambition to lead a Jewish army in the battles ahead. Wilenski came away feeling Wingate was the most remarkable man he had ever met. He introduced Wingate to David HaCohen, one of the prominent Jews in Haifa. HaCohen approached the meeting in a cautious mood, expecting disappointment from the British officer. Anti-Semitism was common and often openly expressed, and British officers were serving with Arab military units. Instead the two men ended up discussing Zionism, and Wingate asked to be given a chance to prove himself to the Jewish community. Wingate told HaCohen that, "I count it my privilege to help you fight your battle. To that purpose I want to devote my life."5 Wingate soon made friends with the top Jewish leaders. The secretary of the Jewish Agency (future prime minister of Israel) Moshe Sharrett was one with whom he formed a strong friendship. He was introduced to David Ben-Gurion (Zionist leader and future prime minister) and became close to Chaim Weizmann, the Zionist movement's leader (future president).

Military Ideas

In 1938 clashes between marauding Arab guerillas and British forces were being instigated at the guerillas initiative. While numbering no more than 1500-2000 active fighters, they were backed by 4-5 times more in part-time combatants & non-combatants.6 They were disrupting communications and civil administration, and extracting vengeance against Arabs suspected of cooperating with the authorities. Operating freely at night in small groups of no more than 15-30 men (rarely coming together for larger attacks in formations larger than 100), they would strike quickly and then slip away, sometimes with the aid of some of the locals.7 For support, some villagers, town dwellers, herders and even police were acting as their eyes and ears. Other times, they would assault nearby villages for supplies and terrorize for control. Raiders, composed of foreign Arab volunteers, and arms were also infiltrating across the border from neighboring Lebanon and Syria despite British efforts to stop the flow. A professional Syrian officer named Fawzi al-Quawgji infiltrated into Palestine in an attempt to try to organize and coordinate the guerilla bands, which were operating in their local areas without a higher command control.

In 1938 clashes between marauding Arab guerillas and British forces were being instigated at the guerillas initiative. While numbering no more than 1500-2000 active fighters, they were backed by 4-5 times more in part-time combatants & non-combatants.6 They were disrupting communications and civil administration, and extracting vengeance against Arabs suspected of cooperating with the authorities. Operating freely at night in small groups of no more than 15-30 men (rarely coming together for larger attacks in formations larger than 100), they would strike quickly and then slip away, sometimes with the aid of some of the locals.7 For support, some villagers, town dwellers, herders and even police were acting as their eyes and ears. Other times, they would assault nearby villages for supplies and terrorize for control. Raiders, composed of foreign Arab volunteers, and arms were also infiltrating across the border from neighboring Lebanon and Syria despite British efforts to stop the flow. A professional Syrian officer named Fawzi al-Quawgji infiltrated into Palestine in an attempt to try to organize and coordinate the guerilla bands, which were operating in their local areas without a higher command control.

While impressed with the devotion & willingness to sacrifice in the Haganah, Wingate was exasperated by the defensive nature of the Jewish forces. He realized that they could not halt the violence with their defensive tactics of fortified settlements. The policy of restraint meant the Haganah was ceding the initiative and mobility to the Arab guerillas. The British were trying to balance an active defense with mobile sweeps & strikes, with holding important static positions in order to maintain effective government control. Mobile columns & patrols were sent out to deny the rebels any sanctuary and to hunt them down. They became consistent and routine in their movements and their actions. With the enemy often indistinguishable from their civilian base and troops often quartered near Arab civilian areas, "it was very difficult to keep operations conducted in a largely hostile civilian milieu secret, and so the element of surprise was lost; at the same time, reliable information about the enemy was hard to come by."8 Commented one Jewish official on a big sweep by British forces, "They marched over hills and valleys, and in the end emerged with some rusty Turkish pistols and a few empty rounds of ammunition...The Arab gangsters just hid their arms and mingled with the population of the villages. Not only did the huge British army find absolutely nothing, it discredited and ridiculed itself in the eyes of the whole population."9 In 1938 General Archibald Wavell, the temporary acting commander of British military forces in Palestine, was forced to admit these and other actions such as aerial bombing had only "a temporary effect."10 Wingate thought there was a better way to bring an end to violence against the Jewish community and stabilize the British colony.

While impressed with the devotion & willingness to sacrifice in the Haganah, Wingate was exasperated by the defensive nature of the Jewish forces. He realized that they could not halt the violence with their defensive tactics of fortified settlements. The policy of restraint meant the Haganah was ceding the initiative and mobility to the Arab guerillas. The British were trying to balance an active defense with mobile sweeps & strikes, with holding important static positions in order to maintain effective government control. Mobile columns & patrols were sent out to deny the rebels any sanctuary and to hunt them down. They became consistent and routine in their movements and their actions. With the enemy often indistinguishable from their civilian base and troops often quartered near Arab civilian areas, "it was very difficult to keep operations conducted in a largely hostile civilian milieu secret, and so the element of surprise was lost; at the same time, reliable information about the enemy was hard to come by."8 Commented one Jewish official on a big sweep by British forces, "They marched over hills and valleys, and in the end emerged with some rusty Turkish pistols and a few empty rounds of ammunition...The Arab gangsters just hid their arms and mingled with the population of the villages. Not only did the huge British army find absolutely nothing, it discredited and ridiculed itself in the eyes of the whole population."9 In 1938 General Archibald Wavell, the temporary acting commander of British military forces in Palestine, was forced to admit these and other actions such as aerial bombing had only "a temporary effect."10 Wingate thought there was a better way to bring an end to violence against the Jewish community and stabilize the British colony.

photo caption

General Wavell. While with a traditional military background he was an unorthodox thinker, and well respected. He was able to see in Wingate his professional abilities, and his first experience with him made a lasting impression. Wavell was to have a significant role in all military campaigns Wingate fought in.

Photo courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London

Wingate envisioned carefully selected, small and mobile units of volunteers to fight aggressively and unconventionally. In a report (as laid out in a future, prepared report dated June 5th, 1938 and titled: "Secret Appreciation of Possibilities of Night Movements by Armed Forces of the Crown - With Object of Putting an end to Terrorism in Northern Palestine") he spelled out formally the need for a unique military force. "There is only one way to deal with the situation, to persuade the gangs that, in their predatory raids, there is every chance of their running into a government gang which is determined to destroy them, not by exchange of shots at a distance, but by bodily assault with bayonet and bomb."11 This new unit was to carry the war to the enemy, taking away his initiative and keeping him off-balance. And so it was, "to produce in their minds the belief government forces will move at night and can and will surprise them either in villages or across country."12 The force would be a mixed British-Jewish one operating under his command, moving primarily at night in areas of guerilla activity with the allies of the night: deception, surprise, shock.

The Jewish population he saw as an untapped source of intelligence, security and manpower. Instead of being stationed at British police or military bases he saw units based amid Jewish communities in the north. The Jewish police and the Haganah had good contacts and sources among both Jewish and Arab populations, providing consistent and reliable intelligence. They regularly had business interactions with many Arabs, they recruited Arab individuals, they were exploiting inter-Arab clan and political rivalries for information, and they were familiar with the land. By being based at Jewish settlements the force would remain secure in planning and movements, and would avoid having their movements easily monitored. He felt that Jewish volunteers could make excellent soldiers, better than the average British one due to their motivation and education. The strength the regular British forces would bring would be their formal military training and discipline, equipment, and official support. The name of the new unit was to be the Special Night Squads, the SNS.

Earning Trust

Captain Wingate set about getting his ideas implemented against official disapproval of arming Jews (and the belief that Jews were not a martial race). His openly pro-Jewish beliefs, disdain for military hierarchy, and disheveled professional appearance contributed to factors working against him. Several papers were written and distributed within the British Jerusalem headquarters of the potential effectiveness of a mixed British-Jewish force matched with unconventional tactics. Brigadier Evetts in Nazareth, who was the commander of the brigade covering northern Palestine that Wingate was formally attached to, was busy all hours trying to push out mobile columns and block the Syrian border with static forces. Evetts showed an interest in his ideas and encouraged him. Deciding to circumnavigate the headquarters staff that was opposed to his ideas and his personality, he sought a way to directly meet General Wavell, Palestine's military commander. Investigating the route and timing of the general's journey while he was visiting military bases, Wingate made sure he was there to step in front of his car one day and hold up his hand. Not bothered by the ingenuity of Wingate's approach (and lack of proper protocol), he gave permission for Wingate to climb in. The general listened as the Captain articulated his ideas, though his initial reaction was that Wingate was "an odd creature."13 Wavell was not sympathetic to Zionism, but he did recognize the intelligence of the plan to overcome a sense of military defensiveness and break the guerillas. He gave his approval to raise the force.

Wingate next turned to the Jewish leadership and their hesitancy. Both Wilenski and HaCohen found it difficult to convince others that this British soldier was different and could be an ally. Many of the Yishuv leadership were openly skeptical toward them. Mutual distrust between the Jewish and British sides was strong. While Wingate had the support of Wilenski and eventually Weizmann, he had to fight to get active cooperation. Some Jewish leaders were opposed to changing the policy of restraint, suspicious of this British officer who was asking for the best men of the Haganah to take aggressive action. Frustrated, one day Wingate went to the head of the Jewish Agency in Jerusalem and shouted at him "Why do you flirt with your enemies and ignore your friends?"15 Eventually suspicions cooled and Yitzhak Sadeh, one of the Haganah leaders, came to trust in Wingate's sincerity. He was able to persuade the Haganah to cooperate with Wingate.

photo caption

Yitzhak Sadeh, a military chief of the Haganah in the 1930s and 1940s (and former Russian military officer). He stated of Wingate with his active mind always thinking, "If he had not gone in for a military career, he would undoubtedly have been equally successful in any other field."32

Photo courtesy of the

Israeli Ministry of

Defense, Museum Unit

photo caption

Jewish Supernumerary Police arriving at the site where they would begin to help build the settlement of Hanita.

photo courtesy of the

Israel Government

Press Office

Wingate's work would expand upon and greatly improve the work being done by Sadeh. Under Sadeh's direction, the Haganah was beginning to re-organize to improve its military effectiveness. Some Haganah men, the field companies or Plugot Sadeh, were being taught to patrol in small units and in more remote areas. Their patrols moved along dirt paths and at night set up small ambushes and launched pre-emptive strikes. A small training program was being created to help teach basic military field craft and tactics. But this was limited as Sadeh was facing resistance from others about changing the strategy of passive military defense. Said one future Israeli Army chief-of-staff, "The fact was that, up to Wingate's time, those leading the Haganah were neither scientists in warfare nor artists in warfare, but simply amateurs who had to do what they did for lack of alternative."17 Wingate's arrival and subsequent success would help to turn the fortunes for the Haganah. Sadeh put it as, "For some time we did the same things as Wingate, but on a smaller scale and with less skill. We followed parallel paths, until he came to us, and in him we found our leader."18

Wingate's work would expand upon and greatly improve the work being done by Sadeh. Under Sadeh's direction, the Haganah was beginning to re-organize to improve its military effectiveness. Some Haganah men, the field companies or Plugot Sadeh, were being taught to patrol in small units and in more remote areas. Their patrols moved along dirt paths and at night set up small ambushes and launched pre-emptive strikes. A small training program was being created to help teach basic military field craft and tactics. But this was limited as Sadeh was facing resistance from others about changing the strategy of passive military defense. Said one future Israeli Army chief-of-staff, "The fact was that, up to Wingate's time, those leading the Haganah were neither scientists in warfare nor artists in warfare, but simply amateurs who had to do what they did for lack of alternative."17 Wingate's arrival and subsequent success would help to turn the fortunes for the Haganah. Sadeh put it as, "For some time we did the same things as Wingate, but on a smaller scale and with less skill. We followed parallel paths, until he came to us, and in him we found our leader."18

In March of 1938 the Jewish Agency decided to build a fortified settlement at Hanita in the north next to the Lebanese border. It was picked because it would help fortify the Jewish presence in the Galilee and close a gap in the frontier to Arab infiltration from Lebanon. Hundreds feverishly worked on the "stockade and watchtower" project during the daylight hours of March 21st. During the first night they were attacked.

The attacks went on for several days, the raiders striking & retreating at will. The Jewish force was unable to entrap them before they reached the border. Eventually two young Haganah leaders Yigal Allon & Moshe Dayan did strike at the marauders. Into this situation in April Wingate arrived with rifles and a dictionary, and a letter from Haganah headquarters stating he was to be shown around.

The attacks went on for several days, the raiders striking & retreating at will. The Jewish force was unable to entrap them before they reached the border. Eventually two young Haganah leaders Yigal Allon & Moshe Dayan did strike at the marauders. Into this situation in April Wingate arrived with rifles and a dictionary, and a letter from Haganah headquarters stating he was to be shown around.

Wingate brought an energy and direction into the Jewish force. His trip through dangerous northern territory alone was a first. His arrival at Hanita produced a sensation, Haganah soldier Zvi Brenner remembering, "We gazed at him in amazement. His daring at coming up to Hanita alone at night astonished us and made a tremendous impression."20 Brenner was assigned to watch him closely. He remembered how, "I slept in a tent with him so as to watch his steps...In those days no-one was allowed to leave the settlement without the express permission of the commander, but Wingate used to disappear and return after a couple of hours. We had meanwhile searched [for] him in vain while he had thoroughly explored the vicinity."22 With the authority given to him by the British and Haganah authorities, Wingate would finally able to get the Haganah forces to undertake the aggressive action Sadeh had been trying to push through unsuccessfully.

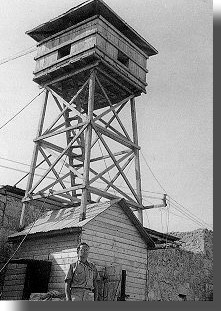

photo caption

A stockade and watchtower settlement similar to the one at Hanita. Hundreds would secretly prepare the groundwork for a settlement. Then working non-stop, in 24 hours the bases of a settlement would be constructed. The first priorities were preparing fortifications (barracks, watchtower, wooden walls) against expected Arab attacks.

photo courtesy of the

Israel Government

Press Office

Meeting with Haganah commanders, he spoke to them about the need for forward mobile, defense. "Instead of defending the colony from inside, we should go out and meet the enemy in the open, near his villages. The Haganah were thinking defense of the settlement meant being near the settlement, not at an ambush near the exit from an Arab village, a new concept. This was something entirely new for us, and we had still no experience in that kind of warfare," wrote Brenner.23 One day he spoke to the gathered force of the success of his efforts in the Sudan. He spoke initially in Hebrew, but was forced to switch to English, as his audience could not understand his accent. They did recognize the biblical quotations interlaced in his speech. He said they would go out that night and set an ambush near an Arab village to catch the attackers as they were moving, to strike first. One listening and watching Wingate intensely was Dayan. "When he spoke, he looked you straight in the eye as someone who seeks to imbue you with his own faith and strength," Dayan remembered.24 That night the force marched along hill ridges instead of the paths, Wingate insisting upon walking ahead of the force to scout. Nearing the targeted village, he split the force into two groups so as to create a crossfire, but no armed raiders appeared. Next targeted was the village of Jordiah on the border, being used a base for attacks against Hanita. Wingate led a small nighttime raiding force with his excellent navigation skills through the rough terrain using the stars, a map, and compass. Remarked Sadeh, "I still do not know how Wingate found his direction, but I think he possessed a certain instinct."25 Forced to fight its way into the village, they inflicted casualties while suffering none. Such actions began creating lessons and ideas.

Meeting with Haganah commanders, he spoke to them about the need for forward mobile, defense. "Instead of defending the colony from inside, we should go out and meet the enemy in the open, near his villages. The Haganah were thinking defense of the settlement meant being near the settlement, not at an ambush near the exit from an Arab village, a new concept. This was something entirely new for us, and we had still no experience in that kind of warfare," wrote Brenner.23 One day he spoke to the gathered force of the success of his efforts in the Sudan. He spoke initially in Hebrew, but was forced to switch to English, as his audience could not understand his accent. They did recognize the biblical quotations interlaced in his speech. He said they would go out that night and set an ambush near an Arab village to catch the attackers as they were moving, to strike first. One listening and watching Wingate intensely was Dayan. "When he spoke, he looked you straight in the eye as someone who seeks to imbue you with his own faith and strength," Dayan remembered.24 That night the force marched along hill ridges instead of the paths, Wingate insisting upon walking ahead of the force to scout. Nearing the targeted village, he split the force into two groups so as to create a crossfire, but no armed raiders appeared. Next targeted was the village of Jordiah on the border, being used a base for attacks against Hanita. Wingate led a small nighttime raiding force with his excellent navigation skills through the rough terrain using the stars, a map, and compass. Remarked Sadeh, "I still do not know how Wingate found his direction, but I think he possessed a certain instinct."25 Forced to fight its way into the village, they inflicted casualties while suffering none. Such actions began creating lessons and ideas.

Decision

Through the spring of 1938 the guerilla war continued, concentrated in the northern and central regions of Galilee, Samaria and Jerusalem. The rebels had failed to establish a central command structure for strategic coordination, due to political rivalries and personal hatreds. They were avoiding direct attacks against military units, realizing their inferiority in conventional actions. And their weapons were of poor quality. But they were enjoying success in launching hit-and-run raids, ambushes, sniping. They were obtaining some support from across the spectrum of the Arab population, either from sympathy or intimidation. Cross-border smuggling and criminal activities were ensuring a supply of weapons and volunteers. Bombings and murder were continuing to put civilians at risk as much as soldiers, with colonial officials targeted for assassination. Each month from the end of 1937 through the spring of 1938, there were hundreds of terrorist acts, dozens of murders & attempted assassinations.27 The Yishuv was beginning to suffer heavy casualties from guerilla attacks in rural areas and terrorist actions in the cities, averaging 50 deaths per month.28 Government stations were being raided, and now saboteurs were striking at the strategic British Iraqi Petroleum Company's oil pipeline. Running through the Galilee to the port of Haifa, attacks were concentrated in the eastern region & against nearby communications. With no reinforcements on the way due to the threat of war in Europe, army forces were limited to 8 infantry and 1 armored car battalions (two brigades), backed by some air force squadrons.29 With these factors in mind, in May the new British commander in Palestine, General Haining, gave approval to continue the forming of the SNS to put a stop to the attacks against the pipeline and other acts of terrorism.

1. General Yigal Yadin in Israel Defense Force, Haganah Museum documents 143-12.

2. Christopher Sykes, Orde Wingate (New York: World Publising Company, 1959), p.110.

3. Derek Tulloch, Wingate in War and Peace (London: History Book Club, 1972), 46.

4. Yosef Eshkol, A Common Soldier (Tel Aviv: Israeli Ministry of Defense, 1993), p.112-13.

5. Sykes, 112.

6. Michael Cohen and Martin Kolinsky (eds), Britain and the Middle East In The 1930s (New York: St. Martins Press, 1992), 182 & 189.

7. Cohen and Kolinsky, 182.

8. Ibid, 150.

9. Trevor Royle, Orde Wingate, Irregular Soldier (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1995), 118.

10. Cohen and Kolinsky, 155.

11. Israel Defense Force, Haganah Museum documents 80-69-26.

12. Haganah Museum documents 80-69-26.

13. John Connell, Wavell: Scholar & Soldier (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1964), 196.

14. Connell, 189.

15. Sykes, 144.

16. Haganah Museum documents 80-69-26.

17. General Yigal Yadin in Israel Defense Force, Haganah Museum documents 143-12.

18. Yigal Allon, The Making of Israel's Army (New York: Universe Books, 1970), 10.

19. Eshkol, 128.

20. Dov Jirmiyahu in Israel Defense Force, Haganah Museum documents 12-0014.

21. Eshkol, p.87.

22. Israel Defense Force, Haganah Museum documents 11-16.

23. Haganah Museum documents 11-16.

24. Moshe Dayan, Moshe Dayan: Story of My Life (New York: William Morrow & Co., 1976), 45.

25. Israel Defense Force, Haganah Museum documents 80-137-3.

26. Sir Hugh Foot, A Start In Freedom (New York: Harper & Row, 1966), 48-9.

27. Cohen and Kolinsky, 155-56.

28. Shabtai Teveth, Moshe Dayan: The Soldier, The Man, The Legend

(Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1973), 97.

29. Cohen and Kolinsky, 149.

30. Howard Sachar, A History of Israel

(New York: Alfred Knopf, 1976), 215.

31. Foot, 52.

32. Haganah Museum documents 80-137-3.