H o n o u r T o N o t o r i e t y

T h e A c h i e v e m e n t

T h e A c h i e v e m e n t

T h e A c h i e v e m e n t

The Small Unit War

photo caption

A detachment of SNS setting out near Ein Herod on an exercise. Wingate would lead many patrols himself believing, "One cannot lead people in unortho-

dox directions without showing them how things must be done... Only by personal example."30

Photo courtesy of the

Israel Government

Press Office

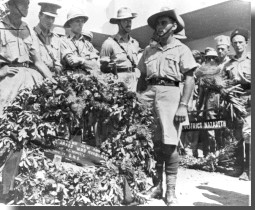

photo caption

From left, King-Clark, Wingate, Grove & Bredin of the SNS at funeral of Chaim Sturmann of Kibbutz Ein Harod.

Photo courtesy of the

Israel Haganah Museum

Operations were also growing in scope and possibilities. Due to the small size of the Special Night Squads Haganah units were also used at times in cooperation, coming under Wingate's control for actions. The SNS also provided cover for operations of the force. When the Haganah wished to carry out a certain operation which it was incapable of carrying out, the task was transferred to the Special Night Squads. Both Haganah and police and the more organized Fo'sh units (such as those of Allon & Dayan) worked with the SNS. They learned to operate as military units at all levels, from small squad and platoon size forces to engaging in company size operations. Haganah field companies were harassing the rebels with the methods of the SNS, ambushing them near their bases, patrolling around the clock, launching retaliatory strikes. They were learning to move at night in rough country, launch quick raids, and then rapidly disengage and withdraw. Together the two forces were confidently engaging larger sized forces.

Through the rest of the summer and into autumn, the effectiveness of the SNS continued against hostile bands. Clashes and raids were undertaken at places throughout the hills of the Galilee and at the borders at the behest of the SNS, much of this due to the good intelligence they were receiving. The remnants of the Arab band from Dabburiya were successfully ambushed at Bira (14 dead)2 by Bredin, and at the Horns of Hittin King-Clark successfully ambushed an enemy group. Engagements favorable for the SNS kept occurring, such as at the wadi ford Umm Mejadda against arms smugglers, and near the villages of Danna & Khaukab el Hauva against assembling rebel groups. The SNS was keeping the guerillas off-balance and thinking defensively, inflicting heavy casualties. The oil pipeline which was being sabotaged about once every night, remained free from attacks for months in a row. Often times several squads would combine for larger patrols and raids. One example was in early September, at the village of Lid el-Awadin (Khirbet Beit Lid), just west of Afula and south of the pipeline.

Intelligence determined a group of guerillas was encamped on the outskirts of Lid el-Awadin, serving as a base for attacks and arms smuggling. Wingate set a trap to get the Arab force to revel themselves in the open and do battle in daylight. A rumor was spread that Wingate's men at Ein Harod were leaving on a routine patrol, in the direction away from the village. At night vehicles secretly picked the men up and dropped them in a ravine, the trucks never stopping as they drove toward Haifa with the men silently leaping off in the dark. In the morning they crossed the fields and took up positions in a semi-circle around Lid el-Awadin. A truck carrying members of the Jewish Police (including Moshe Dayan) dressed as workers drove into the village, the bait. A group of some of the armed Arabs advanced toward what they thought was the easy target of the truck. Then hidden SNS & Haganah onboard revealed their weapons and opened fire. The gunfire alarmed the rest of the Arabs encamped in the village and they headed for safety away from the gunfire, to the northeast. Here they ran into the ambush set by Wingate. Turning to flee to the southeast they hit another ambush party led by Bredin. Enemy casualties numbered 14 dead (including the gang leader) and others captured from a force of close to 40, with no friendly casualties.3 From the dead terrorist leader valuable intelligence was gleaned from papers listing civilian supporters. This and similar actions such at Danna and again at Dabburiya in which several gangs were destroyed were successful in halting attacks. Hostile action in northern Palestine was being reduced to occasional murders, sabotage & mining.

While Wingate treated ordinary Arab citizens with respect & targeted only known guerillas, there was one exception. In the middle of September the leader of the Ein Harod settlement, Chaim Sturmann, was killed by a land mine. Wingate reacted with his emotions upon hearing the death of his close friend. He immediately ordered SNS men to the Arab village of Beit Shean, which was known to harbor guerillas. Wanting to install in the hearts of the inhabitants' fear of the authorities to help prevent any future actions, Wingate in an uncontrolled fury descended upon the village. Several civilians were killed and some buildings destroyed as he attempted to find the perpetrators. Sturmann and Wingate had often argued over the idea of collective punishment. Sturmann had counseled moderation and cooperation with Arabs, and would argue that punishing an entire village for aiding guerillas or harboring them was wrong and counter-productive. Wingate would argue he wanted villagers who assist guerillas to be more frightened of the SNS and British terror than of guerilla terror. The harsh reality of fighting a guerilla war meant at times the SNS was forced to resort to

hard tactics

to punish Arab civilians cooperating with the terrorists, and who lived in the vicinity of the punctured pipeline. One SNS member summing up the guerilla war dilemma faced by Wingate and the SNS said, "On the one hand he, demanded that the innocent not be harmed. On the other hand, he knew that he faced a dilemma: can one observe this rule in a battle against gangs which receive assistance from the residents of the villages?"6 After Beit Shean Wingate did express regret for his actions there.

While Wingate treated ordinary Arab citizens with respect & targeted only known guerillas, there was one exception. In the middle of September the leader of the Ein Harod settlement, Chaim Sturmann, was killed by a land mine. Wingate reacted with his emotions upon hearing the death of his close friend. He immediately ordered SNS men to the Arab village of Beit Shean, which was known to harbor guerillas. Wanting to install in the hearts of the inhabitants' fear of the authorities to help prevent any future actions, Wingate in an uncontrolled fury descended upon the village. Several civilians were killed and some buildings destroyed as he attempted to find the perpetrators. Sturmann and Wingate had often argued over the idea of collective punishment. Sturmann had counseled moderation and cooperation with Arabs, and would argue that punishing an entire village for aiding guerillas or harboring them was wrong and counter-productive. Wingate would argue he wanted villagers who assist guerillas to be more frightened of the SNS and British terror than of guerilla terror. The harsh reality of fighting a guerilla war meant at times the SNS was forced to resort to

hard tactics

to punish Arab civilians cooperating with the terrorists, and who lived in the vicinity of the punctured pipeline. One SNS member summing up the guerilla war dilemma faced by Wingate and the SNS said, "On the one hand he, demanded that the innocent not be harmed. On the other hand, he knew that he faced a dilemma: can one observe this rule in a battle against gangs which receive assistance from the residents of the villages?"6 After Beit Shean Wingate did express regret for his actions there.

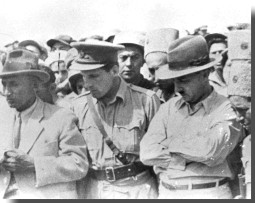

photo caption

Wingate at Ein Harod funeral with Moshe Sharrett on his left. Wingate was to admit to him in 1937 he adopted Zionism as a religion. Wrote Sharrett, "He had a passionate & violent affection, yes, his affection was over-

powering."32

Photo courtesy of the

Israel Haganah Museum

The Taskmaster

Wingate worked at various schemes to increase both the size of his force and Jewish military training. His request for 2 more officers and several more British infantry squads was denied by his superiors. But he gained permission at the end of August to set up an NCO training course at Ein Harod, with the Jewish leadership footing the bill. The Haganah assigned about 100 of its best men.7 Among the lectures Wingate gave was on the cause: "Know what you are fighting for and love what you know."8 Drilled hard day and night, "The pressure on those in the course was great, but the feeling that they were participating in a heroic venture was something all shared."9 Many who passed through there remember Wingate

declaring,

"We are establishing here the foundation of the Army of Zion...If it fights it will achieve its independence in its land."11

Wingate worked at various schemes to increase both the size of his force and Jewish military training. His request for 2 more officers and several more British infantry squads was denied by his superiors. But he gained permission at the end of August to set up an NCO training course at Ein Harod, with the Jewish leadership footing the bill. The Haganah assigned about 100 of its best men.7 Among the lectures Wingate gave was on the cause: "Know what you are fighting for and love what you know."8 Drilled hard day and night, "The pressure on those in the course was great, but the feeling that they were participating in a heroic venture was something all shared."9 Many who passed through there remember Wingate

declaring,

"We are establishing here the foundation of the Army of Zion...If it fights it will achieve its independence in its land."11

Wingate was setting high standards, leading by example of formidable willpower and discipline. Wingate's self-discipline on patrol, his energy in setting and leading actions, and his commitment to the Zionist caused impressed the SNS men as much as his military professionalism. Besides stressing military tactics such as the importance of fire and silence discipline, he stressed that a commander had responsibilities not privileges, and that he was responsible for his men. Said an SNS veteran of him, "Wingate maintained strong discipline, which he did not teach us by military phrases but by personal example and immediate responses...If you would take something with you that interfered with the battle, you would be punished. If there was no bullet in the rifle barrel, you would be punished. If you kicked a stone, you would be punished. If you fired without being ordered to do so, that was the worst offense."12 It also explained and created a toleration of his harsh physical punishment for grievous errors, as he was also harsh on himself.

photo caption

SNS men training. At the non-commissioned officers training program he set up in September, he cautioned his students about mimicking everything about the professional British army stating, "Learn his discipline and calmness but don't imitate his brutality, stupidity and drunkenness."31

Photo courtesy of the

Israel Government

Press Office

photo caption

Zvi Brenner, who served as one of the Jewish officers in an SNS platoon and later as Wingate's bodyguard. Brenner was not too pleased to be assigned as bodyguard, knowing Wingate when driving liked to have one hand on the wheel and with the other hand hold a loaded rifle.

Photo courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London

This was discipline which he rigidly enforced with verbal and physical punishment. Response to a breach in the iron discipline he demanded was quick and decisive. Once, a patrol was returning up the side of a wadi to its trucks, thirsty and tired. The first man up was a British officer and started to drink water. Wingate rebuked him, telling him that in the future he was to ensure his men drank first. Then he was ordered by Wingate to go down the wadi and climb up again. On one patrol as it was moving up a hill a stone started rolling down, and with this break in silence Wingate halted movement. He asked who the commander was, and when the man approached him he slapped him. Out on patrol one night, the oldest man who was a founder of Ein Harod kibbutz opened fire on a suspicious shadow without thinking. Wingate when over to him and grabbed him by the cheek, saying to the man in Hebrew, "Why without and order? Why without an order?"13 His willingness to sacrifice for their cause, his boundless energy and professionalism he was creating fostered respect despite such actions. He would not only endure the hardships of patrols but afterwards would not hesitate to admit if he made a mistake, "He wanted to know whether, had we done this or that in a different way, we would have achieved more. In reality, that was self-criticism and criticism of the unit."14

This was discipline which he rigidly enforced with verbal and physical punishment. Response to a breach in the iron discipline he demanded was quick and decisive. Once, a patrol was returning up the side of a wadi to its trucks, thirsty and tired. The first man up was a British officer and started to drink water. Wingate rebuked him, telling him that in the future he was to ensure his men drank first. Then he was ordered by Wingate to go down the wadi and climb up again. On one patrol as it was moving up a hill a stone started rolling down, and with this break in silence Wingate halted movement. He asked who the commander was, and when the man approached him he slapped him. Out on patrol one night, the oldest man who was a founder of Ein Harod kibbutz opened fire on a suspicious shadow without thinking. Wingate when over to him and grabbed him by the cheek, saying to the man in Hebrew, "Why without and order? Why without an order?"13 His willingness to sacrifice for their cause, his boundless energy and professionalism he was creating fostered respect despite such actions. He would not only endure the hardships of patrols but afterwards would not hesitate to admit if he made a mistake, "He wanted to know whether, had we done this or that in a different way, we would have achieved more. In reality, that was self-criticism and criticism of the unit."14

The constant high tempo he had kept up over the months with the hard work and the stress of combat finally caught up to him. After the action at Beit Lid, Wingate was overcome with mental and physical exhaustion. After reporting the action his old leg wound opened up. After bandaging this up, he went to Brigadier Evetts with some of the intelligence collected. While discussing this information,

he collapsed and had to spend some time on a couch. Success also resulted in a bounty being placed on Wingate's head by the guerillas. One thousand British Pounds (a considerable sum back then) was offered for Wingate's death by an Arab guerilla leader. Wingate argued with the Haganah leadership about traveling with bodyguards, and in the end agreed to take on a single bodyguard. The Haganah assigned Zvi Brenner to be Wingate's bodyguard. Once in Haifa Wingate was staying at Wilenski's house after a night patrol. Traveling in his car the next day during the daylight an Arab threw a grenade into it, but it failed to explode. Back at the house, "He suffered a reaction which left him hardly able to move and in the throes of a trembling fit."15

he collapsed and had to spend some time on a couch. Success also resulted in a bounty being placed on Wingate's head by the guerillas. One thousand British Pounds (a considerable sum back then) was offered for Wingate's death by an Arab guerilla leader. Wingate argued with the Haganah leadership about traveling with bodyguards, and in the end agreed to take on a single bodyguard. The Haganah assigned Zvi Brenner to be Wingate's bodyguard. Once in Haifa Wingate was staying at Wilenski's house after a night patrol. Traveling in his car the next day during the daylight an Arab threw a grenade into it, but it failed to explode. Back at the house, "He suffered a reaction which left him hardly able to move and in the throes of a trembling fit."15

Closing Actions

In Fall of 1938 the violence beginning to pick up again. Raids against police posts and roads and government administrative buildings increased. The army temporarily lost control of several urban areas including the Old City of Jerusalem for a week. In late September General Haining reported to London that regarding the situation in the north, "The situation was such that civil administration and control of the country was, to all practical purposes, non-existent."16 October saw the beginning of an increase in terrorism with 188 people being killed by Arab terrorist.17 That month the Jewish population of the town of Tiberias along the Sea of Galilee was targeted. A massacre of civilians including children took place on the 2nd of the month as group of rebels infiltrated into the Jewish quarter. The British battalion stationed in the town was scattered for the weekend and did not intervene, many remaining pinned down in their barracks and taking cover in the streets. Dead civilian bodies were burnt, the attackers then taking to looting and drinking.

photo caption

Captured rebel arms. Appreciating Wingate's success, General Haining didn't appreciate his subordinate's independence when it came to obeying orders & supplying information. He once considered his dismissal stating, "Here is a fellow Wingate who makes no secret of the fact that he only obeys orders which suit him."33

Photo courtesy of the

Imperial War Museum, London

Wingate was out with a small SNS force nearby that night setting an ambush and heard the news. He took a handful of men with him to Tiberias to set an ambush for the Arab raiders on the road leading west out of town. The road leading out steeply climbs and backtracks along a hill, and here Wingate and his men waited. He struck the retiring Arab force, and the action was followed up by an attack of a Fo'sh company led by Allon. Together they inflicted around 40-50 casualties, out of some estimated 70 attackers.18 The Bitish military commander of the Middle East, General Ironside, happened to be in the country. He quickly rushed to the scene. The poor performance of the British battalion and his sacking of its commander, and the death and destruction put him in a foul mood. At the top of the hill outside Tiberias he encountered the bearded Wingate in his pith helmet. "And who are you?" he demanded of him. "I'm Wingate," came the firm reply back.19 Listening to his accomplishments, and contrasting his work with the ineffective British effort, Wingate fostered a lasting impression upon the general.

The next day pursuit of a terrorist band ended in success at Mount Tabor. On the way back to Nazareth Wingate recognized several guerilla leaders traveling in a passing taxi. With the nearby SNS platoon led by Bredin they chased it to Dabburiya where the remnant of the guerilla group had taken refuge. Wingate and some men fought their way into Dabburiya and collected 15 enemy dead.20 Bredin and the rest of his platoon followed some escapees up Mount Tabor, encountering resistance and exchanging gunfire around the Benedictine monastery. Contact was hurriedly sent to a local RAF squadron. Several aircraft eventually appeared but with the inability to tell friend from foe they proceeded to bomb and strafe the SNS men, fortunately with no casualties. This action was to be Wingate's last in command of the SNS.

The next day pursuit of a terrorist band ended in success at Mount Tabor. On the way back to Nazareth Wingate recognized several guerilla leaders traveling in a passing taxi. With the nearby SNS platoon led by Bredin they chased it to Dabburiya where the remnant of the guerilla group had taken refuge. Wingate and some men fought their way into Dabburiya and collected 15 enemy dead.20 Bredin and the rest of his platoon followed some escapees up Mount Tabor, encountering resistance and exchanging gunfire around the Benedictine monastery. Contact was hurriedly sent to a local RAF squadron. Several aircraft eventually appeared but with the inability to tell friend from foe they proceeded to bomb and strafe the SNS men, fortunately with no casualties. This action was to be Wingate's last in command of the SNS.

An Inglorious End

His pro-Zionism and involvement in the the politics of the Zionist cause finally reached the limit his superiors would tolerate. In November he took leave to travel to England. He met with Ben-Gurion and Weizmann to discuss ways of influencing British decision-makers on favorable schemes of partition. His suggestions were often less than diplomatic, causing Weizmann to later write "Much as I admired and loved Wingate I did not think that his diplomatic activities in any way matched his military performance or his personal integrity."24 Wingate testified before a commission examining partition and spoke favorably about the value of a Jewish state and of his reasons for doing so, "Nowadays people seem to imagine that impartiality means readiness to treat lies and truth the same, readiness to hold white as bad as black and black as good as white...I believe that righteousness exalteth a nation and righteousness does not mean playing off one side against the other while you guard your own interests."23 He also spoke to a cabinet minister and newspaper editors on how the Jews were the only reliable force in the region Britain could rely upon. For these actions he was ordered back to Palestine, his military superiors angry at this breach of military protocol and political partisanship. When he returned he was removed from command of the SNS and was transfered to staff intelligence duties in Jerusalem.

photo caption

SNS unit members pose for a photograph. Divisional commander General Bernard Montgomery promised to award decorations to the men who served in the SNS, but nothing was done. Bredin, Grove, and King-Clark would all go on to serve during WWII and achieve higher rank.

Photo courtesy of the Israel Haganah Museum

By early 1939 the violence was becoming more manageable again thanks to the SNS, Haganah Plugot Sadeh, and British forces. These forces were having a serious impact upon the Arab rebels, and they were forced to split into smaller units and resort to sniping and terrorism. With the Munich Agreement in Europe, British troop strength was doubled to 20 infantry and cavalry battalions.26 General Haining stationed troops in some Arab villages, denying their population to the rebels and protecting helpful villagers and the surrounding territory. A fence was installed along the border with French Lebanon and patrolled. Large sweeps of population centers, more arrests and executions, and strict movement and economic controls were instituted. More Arab civilians began to provide information on rebels and arms locations. War in Europe was on the horizon, and looking for all strategic advantages to defend the region and route through the Suez, and to remove commitments to a people they viewed as a nuisance, Britain moved to limit Arab hostility and Jewish power. The Foreign Secretary warned against employment of the SNS, "on general grounds of avoiding any action which might give the impression in neighboring countries that Jewish troops are henceforth to be used for offensive purposes."27 This meant closing the camp at Ein Harod in December.

Starting in January of 1939, British soldiers began fill all the ranks of the SNS (now under the command of Bredin), and it moved to the northern border. By March the unit was all-British and operations were wound down by the summer. And in keeping with this policy, General Haining decided to transfer a non-neutral Wingate out. In May Captain Wingate's orders came

transferring him

to England.

Starting in January of 1939, British soldiers began fill all the ranks of the SNS (now under the command of Bredin), and it moved to the northern border. By March the unit was all-British and operations were wound down by the summer. And in keeping with this policy, General Haining decided to transfer a non-neutral Wingate out. In May Captain Wingate's orders came

transferring him

to England.

Wingate was granted permission to say goodbye. The Haganah leaders and men were sad to see "HaYedid" leave. He met with his men and friends to say goodbye and offer some advice and hope for the future. At one kibbutz a farewell was held for him. Upon his entry he was met with applause. He gave a speech saying war with Nazi Germany was imminent and that afterwards there would be a war for Jewish independence that the Jews would win. He urged a more aggressive policy but cautioned against using violence directly against the British authorities. At the end of another farewell party he raised his right hand. Pledging that someday he would return to an independent Jewish homeland, he recited the Biblical verse from the Psalms, "If I forget thee O Jerusalem, let my right arm forget her cunning. If I do not remember thee, let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth, if I prefer not Jerusalem above my chief joy."29

1. Sir Hugh Foot, A Start In Freedom (New York: Harper & Row, 1966), 52.

2. Christopher Sykes, Orde Wingate (New York: World Publising Company, 1959), 167.

3. Yosef Eshkol, A Common Soldier (Tel Aviv: Israeli Ministry of Defense, 1993), 176.

4. Trevor Royle, Orde Wingate (London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1995), 141-2.

5. Rex King-Clark, Free For A Blast (London: Greenville, 1988), 187.

6. Eshkol, 176.

7. Ibid, 189.

8. Sykes, 174.

9. Eshkol, 189.

10. Sykes, 175.

11. Royle, 139.

12. Eshkol, 184.

13. Ibid, 185.

14. Ibid, 184.

15. Sykes, 182.

16. Ian Black & Benny Morris, Israel's Secret Wars (London: Futura, 1991), 14.

17. Sykes, 178.

18. Ibid, 180.

19. Ibid, 180.

20. Eshkol, 170.

21. Norman Rose, The Gentile Zionists (London: Frank Cass, 1973), 111.

22. Royle, 108.

23. Sykes, 166.

24. Rose, 111.

25. Sykes, 194.

26. Ibid, 194.

27. Royle, 149.

28. Ibid, 150.

29. Ron Grossman, Remembering One Of Israel's Founding Fathers - A Protestant Scotsman (Chicago Tribune: April 20, 1998, Tempo Section), 4.

30. Michael Bar-Zohar, Lionhearts, Heroes of Israel (Tel Aviv: Israeli Defense Forces Publishing House, 1997), 37.

31. Sykes, 174.

32. Royle, 110.

33. Sykes, 185.