P r o m i s i n g R o o t s

B e g i n n i n g s

B e g i n n i n g s

B e g i n n i n g s

Early Start

The formal details of his life are the following. Orde was born on February 26, 1903 in British India, the third of seven children born into a military family. His father was a Scottish officer long-serving in the Indian Army from a family of soldiers, his mother coming from a family of soldiers (she was also related to T.E. Lawrence of Arabia) and accomplished scholars. While different in temperament, both parents also had strong religious roots. His mother came from a family of Plymouth Brethren, his father before his conversion to that faith from the Free Church of Scotland. His grandfather had been a missionary in Hungary trying to convert Jews to Christianity for the Church of Scotland. After leaving the army a few years after the birth of Orde, his father helped to run a mission for the poor titled the Central Asian Mission, and contributed much of the family's income to this.

photo caption

John Darby, co-founder of the Plymouth Brethren. Later in his life Orde Wingate would incorporate into his writings and speech appropriate quotations from the Old Testament.

photo courtesy of

Gordon Rainbow

Moving back to Britain while still young, he grew up in a strict religious home. The child of Plymouth Brethren, a Protestant faith which believes in literal interpretation of the Bible and the 2nd Coming of Christ, Orde was subject to intensive religious beliefs and Bible study. Orde had been proceeded by "a long line of Scots Presbyterian ancestors who were full of the belief that salvation was a matter of the wrestling of the individual soul with God and that no authority, however august, must be allowed to come between."2 Memorizing passages of the Bible was a required task while contact with children of differing faiths was strictly regulated. From this developed a stern religious attitude toward life, one of a belief in the fear of God and Original Sin balanced with a hatred of oppression and a disdain for the ordinary. Yet cultural exposures and intellectual pursuits were encouraged, independence being a part of his learning experiences. He enjoyed the freedom to explore the countryside, and opportunity to develop self-reliance and initiative were also abundant.

Though he would go through a period of religious rebelliousness and abandon the formalities of the Plymouth Brethren, his strong religious mind-set would remain. One girlfriend would remember, "he despised the ordinary run of mankind not because of their foolish habits but for not taking themselves as servants of God's will, and making a whole thing of their lives."3 Later in his life this sense of almost religious duty toward life would creep into his thoughts about the evil of war - "War I suppose is a necessary evil - as is a surgical operation. The drugging of one human being by another, the hideous mutilation by the knife, are in themselves evil but become good through a motive. Can one fight in a war with good motives? If not one ought not to fight. I believe one can. I do not believe in carrying on war with hatred for one's enemy. On the contrary. It is a police operation which has in view the welfare of the criminal as well as of the community protected."5

photo caption

Woolwich Military Academy, known as "The Shop." It was used to train branch Artillery and Engineering officer cadets.

photo courtesy of RMAS

After schooling in the spartan secondary school Charterhouse, in 1921 he entered military service with acceptance to the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. He was commissioned a gunnery officer. From his experiences at this strict and conforming, but also with high standards of learning, environment more aspects of his character evolved. He developed a reputation as a non-conformist and a bit anti-social, if intelligent. What grew also was distrust toward blind acceptance of authority. An act of bullying hazing and a dressing down from the Academy Commandant created a sense of humiliation and loneliness in him he was determined never to experience again. One result of this was a zeal to become well educated and mentally agile, a driving energy to ensure he made his mark on the world. He also developed two other characteristics, "a natural sympathy with the oppressed and the underdogs, with a corresponding contempt for the herd and for the establishment."6

He was commissioned in 1923 as a junior artillery officer, in an army recovering from the Great War and shrinking in size. This was a time when the neglected British Army with its small budget and lack of sympathy was "a backwater of British life, complacent, amateurish and comatose."7 Wingate showed a distinct seriousness and intensity when setting out to master whatever task he applied himself to, a "consuming fire of earnestness."8 This applied to hunting and riding, or his army duties. To some, his expressing of unconventional thoughts generated hostility or bemusement, while to others he showed a good sense of humor and humility about himself.

Determined to advance

his career, after beginning to learn Arabic he wrangled an appointment to the British-controlled Sudan through the assistance of a family connection. His father's cousin, Sir Reginald Wingate, had been Lord Kitchener's successor in the Sudan as Governor-General, and later as the High Commissioner in Cairo during WWI.

photo caption

The Mahdi's Tomb. After the conclusive 1898 victory at Omdurman over the forces of the militant Sudanese religious leader, "The Mahdi," Britain ruled the Sudan with just a handful of colonial troops.

photo courtesy of LexicOrient website

To The Sudan

Acting Captain Wingate served with the Sudan Defense Forces from 1928 to 1933. This small British-officered Arab force had been created in the 1920s in response to nationalist uprisings. Defense against a repeat of these and actions against tribes resisting government rule were the major concerns, and actions against criminal gangs operating in the large areas by the Sudanese and Ethiopian border were regular. Wingate was posted to command of an infantry company as part of a battalion near the Ethiopian border to lead patrols against ivory poachers and slave traders, and to show the flag. As at Woolwich, he was admonished by his commanding officer about his non-conservative talk and seemingly unconventional ways. Wingate took this to heart and began to moderate his ways and self-aggrandizing talk. For service in the Sudan presented Wingate with the chance to develop his professional skills.

Command of a self-contained, autonomously operating infantry unit of the Sudanese Defense Forces meant high quality officers were needed. And good junior officers had to be forged. Wingate would be the only European among an all-Sudanese force of Muslim Arabs and African Blacks numbering close to 300 patrolling a large area of the eastern Sudan.11 The commander was required to be both a military officer as well as a colonial administrator. In such a situation there was amply opportunity to develop tactical skills by way of maneuvering in remote areas, by attending to the welfare of the unit, by being responsible for their own military training, and by acting independently of higher authorities in combat. Wingate would learn much about leading men in combat, training and administrating them.

photo caption

Members of the Sudan Defense Forces in bayonet training.

photo courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London

photo caption

Sudan Defense Forces soldiers. Sudan service brought high demands and commitment, and Wingate was to write early on after being posted, "the responsibility is most valuable to a young soldier like myself."

21

photo courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London

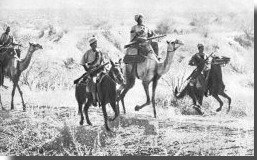

photo caption

Sudan Defense Forces patrol. The size of the force was never more than 5 battalions, or some 4,500 men.22

photo courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London

Actions against poachers and gangs were maintained through infantry patrols, the tracking of movements, supported by aircraft spotting and patrolling. The area of the Sudan Wingate's company operated in eastern Sudan demanded in itself the development of military and personal skills. The desert, hills and scrubland of eastern Sudan was primitive and remote, with little in the way of roads or mechanical transportation. Patrols were tests of endurance. Wingate soon realized facing the poachers and bandits problems common in counterinsurgency. These included the inability to easily seperate the insurgents from civilians, with the small groups of bandits moving among the civilians and in areas frequented by nomads; the difficulty in achieving tactical surprise against forces operating among civilians and which were highly mobile and unpredictable; and the existence of a safe haven, with the criminals able to move regularly across the Ethiopian border. Wingate noticed the standard practices of mobile and irregularly timed patrols were inefficient and obtained poor results. As he wrote in a note, "The measures taken against poachers are limited to the maintenance of highly mobile patrols operating at irregular intervals and in various directions...such wide toothed and occasional combing has not the smallest chance of success in inhabited country."12

Instead of deterring or trying to locate and bring to battle the small poacher gangs by irregular patrols, Wingate found his success by developing other methods. He began to introduce deception, deceiving the enemy about his patrols' ultimate destination and routes. He aimed to supplement such measures with achieving surprise from "using cover and concealment to surround the gangs, then surprise them with attack from all sides."13 Such techniques led to success with one early patrol, from a combination of deception, information from the local population, good tracking, and military skills, all leading to the decimation of one armed criminal gang. Wingate's vigorous writing up of this action brought praise from the Governor-General, stating it was a "very interesting narrative of a most successful expedition conducted with great dash and judgement."14

Concentrating upon the known infiltration and exfiltration routes of the gangs, Wingate was at times able to successfully lay ambushes of border crossing points and tracks. He would write after one patrol that he chose his patrol march along the frontier across desert along the border to achieve surprise since, "by cutting across long stretches of waterless country each line...would be out of reach by warning by fleeing poachers...Should Abyssinians be poaching on Gallegu-Dindar the patrol would be between them and their base. This has special value in view of possible air cooperation."15 Independence of command, the nature of the threat, and characteristic of the country meant Wingate "developed his skill - and taste - for raising, training and leading forces in his own image' free of intervention from above."16

While in the Sudan, the joys of autonomy Wingate experienced was offset by some more unpleasant experiences. With the experiencing of death that came with his profession and fueled by the decent of a sister, Wingate came to the realization of his own mortality and slumped into a temporary

existential depression.

But another form of depression also began to haunt him at times, which he kept to himself, sharing only in letters to a girlfriend.

The attacks of Clinical Depression he would later put it as an 'attacks of the nerves.' Wingate tried to cope with by using them as a fortifying experience, writing "To go through it and come out on the other side still holding on to one's faith and one's reason gives one something of the utmost value. I mean a knowledge of the depths, after that, the ordinary terrors of life are as nothing."18

The attacks of Clinical Depression he would later put it as an 'attacks of the nerves.' Wingate tried to cope with by using them as a fortifying experience, writing "To go through it and come out on the other side still holding on to one's faith and one's reason gives one something of the utmost value. I mean a knowledge of the depths, after that, the ordinary terrors of life are as nothing."18

photo caption

Libyan Sand Sea. On the return journey he encountered a British explorer with what Wingate described as "that hated instrument

of civilization," the automobile.23

photo courtesy of

András Zboray of

Fliegel Jezerniczky Expeditions

In keeping with his character, toward the end of his tour while on leave Wingate set off on a personal expedition of discovery into the Libyan Sand Sea at the eastern end of the Sahara Desert. He was one of several Europeans entranced by exploration and discovery in the unknown North African desert, and like others became romantically drawn into an attempt to find the

legendary oasis of Zerzura.

After cousin Sir Reginald Wingate helped arrange permission with the SDF, in January of 1933 Orde Wingate set off with small party of Arab guides and camels. Challenging himself and the men with him, he traveled by day under the sun to aid in surveying and lived on a Spartan diet. The party navigated past bleak, rocky landscapes, and journeyed through sand dunes amidst the uncharted western Egyptian desert.

While the difficult journey of two months did not produce any evidence of Zerzura (it is thought to have been discovered farther south), Wingate did produce an article for Geographical Magazine. More importantly he tested and discovered more limits of endurance. Marriage came in 1935, his wife Lorna's quick mind and intelligence a match for him (they had met during Wingate's voyage home in 1933 aboard ship).

While the difficult journey of two months did not produce any evidence of Zerzura (it is thought to have been discovered farther south), Wingate did produce an article for Geographical Magazine. More importantly he tested and discovered more limits of endurance. Marriage came in 1935, his wife Lorna's quick mind and intelligence a match for him (they had met during Wingate's voyage home in 1933 aboard ship).

New Postings

Posted back to England in 1933, Wingate now a captain returned to the artillery for several years by serving in units stationed in England. In 1936, he applied for an appointment to Staff College (at Camberley, professional training for higher command) which was thought necessary for advancement. But he failed to get a nomination. He then made a risky and unconventional, but studied, approach to solving this career impasse. The Chief of the Imperial General Staff General Sir Cyril Deverell, also the chairman of the staff college selection committee, happened to be in his area of maneuvers that August.

Wingate approached him, "taking a gamble that Deverell would regard it as initiative - good commanders encourage enterprise in their in their younger officers."19 With his permission he brought to the attention of the commander of the British Army the lack of a staff appointment in spite of his own record and accomplishments. Then presenting a copy of his paper on the Zerzura expedition, he asked if this expedition had been taken into account when his application for a staff position was discussed. Then Wingate voiced disdain of having any ambition to achieve one. The general was intrigued and promised to look into the matter. Impressed with Wingate's Arabic knowledge, the general informed Wingate that while there was no room for him at the army staff colleges in Britain or India, he would find a post suitable to his rank. In September of 1936 orders came assigning captain Wingate to a staff position of intelligence officer, in an army division due to be sent to British Palestine.

next:

Select Wingate in Palestine

![]()

1. Field Marshall Earl Wavell, Soldiers and Soldiering (London: Jonathan Cape, 1953), 106.

2. Trevor Royle, Orde Wingate, Irregular Soldier (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1995), 12.

3. former girlfriend quoted in Derek Tulloch, Wingate in War and Peace (London: History Book Club, 1972), 41.

4. Tulloch, 18.

5. Christopher Sykes, Orde Wingate (New York: World Publising Company, 1959), 503.

6. Peter Mead, Orde Wingate and the Historians (Devon: Merlin Books, 1987), 127.

7. Royle, 36.

8. Mead, 128.

9. Royle, 55.

10. Sykes, 68.

11. Ibid, 63.

12. Simon Anglim, "Orde Wingate in the Sudan, 1928-1933," RUSI Journal, Vol.148, No.3 (June, 2003): 99.

13. Anglim, 98.

14. Royle, 71.

15. Anglim, p.99.

16. Ibid, 99.

17. Sykes, 68.

18. Royle, 75.

19. Ibid, 94.

20. Tulloch, 45.

21. Royle, 61.

22. Royle, 60.

23. Ibid, 78.