T h e I d e a I s F o r m e d

T h e P l a n

T h e P l a n

T h e P l a n

Ideas

photo caption

British troops cross a monsoon-swollen track. Clothing, boots and skin rotted from prolonged exposure during this. Open wounds were a danger to life and limb.

Photograph courtesy of the Imperial War

Museum, London

As the new head of guerilla warfare operations, traveling about that spring Wingate encountered a discouraging situation. Visiting Army field headquarters, he learned from commanders that the shortages of men and equipment left little material for guerilla warfare. While the head of one of the Army Corp fighting in Burma, General Slim, expressed some agreement with him on guerilla warfare, he told Wingate he had no troops no spare as he needed everything he could to hold the Japanese. SOE ran an existing center for training British personal for guerilla warfare with the Chinese, and Wingate went there. He met the chief instructor of the Bush Warfare School, Major Michael Calvert, who was leading small raids against the Japanese. The two discovered they both shared a similar mind-set on the uses of raiding forces.

The land of wartime Burma was one of extremes. While abundant in cultural architecture and natural resources amid lush rain forests, northern and central Burma was no tropical paradise. Mountain ranges cover the borders, thick with jungle. Interior rain forests were trackless with steep ridges, filled with vines & briers amid rotting vegetation. This alternates with fields and sharp elephant grass as tall as a man, or with thick bamboo thickets obscuring visibility to only meters. Divided up by river valleys and mountainous ridges running north to south, interior communications were poor and forced to run this direction. Summer humidity could reach up to 115 degrees Fahrenheit in the open central plains. During the rainy Monsoon period (May to September) up to 200 inches of rain could fall, flooding fields and river regions and sweeping away weak bridges. This often made mules and horses the only reliable transport in the narrow jungle trails and the muddy paths. To this were added swarms of leeches, clouds of mosquitoes as well as snakes & ticks.

The land of wartime Burma was one of extremes. While abundant in cultural architecture and natural resources amid lush rain forests, northern and central Burma was no tropical paradise. Mountain ranges cover the borders, thick with jungle. Interior rain forests were trackless with steep ridges, filled with vines & briers amid rotting vegetation. This alternates with fields and sharp elephant grass as tall as a man, or with thick bamboo thickets obscuring visibility to only meters. Divided up by river valleys and mountainous ridges running north to south, interior communications were poor and forced to run this direction. Summer humidity could reach up to 115 degrees Fahrenheit in the open central plains. During the rainy Monsoon period (May to September) up to 200 inches of rain could fall, flooding fields and river regions and sweeping away weak bridges. This often made mules and horses the only reliable transport in the narrow jungle trails and the muddy paths. To this were added swarms of leeches, clouds of mosquitoes as well as snakes & ticks.

Ideas swarming in Wingate's mind as he saw Burma fall to the Japanese become constructed into plans. In late April Wingate found himself on the Joint Planning Staff at general headquarters staff in New Delhi, set up to create plans for the re-conquest of Burma. He realized that given the poor condition of the army and lack of troops, Japanese expertise, and the hostility of the lowland Burmese to British rule there could be no true guerilla warfare as in Ethiopia. Having thought deeply about the task at hand instead came up with what he called "Deep Penetration" or "Long-Range Penetration." This was the idea of an indefinite long-range raid behind enemy lines in conjunction with a regular offense but relying upon aircraft for support.

photo caption

Wingate planning. He realized a small force could inflict damage all out of proportion to its size in the vast & difficult land. Columns could achieve, "results by skillful concentration at the right time & the right place, when they will deliver the maximum blow against the enemy...the method of dispersal is only a means to achieve ultimate concentration."28

photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

Wingate believed a properly trained and supported force could operate for some time deep behind enemy lines against vulnerable and important targets, damaging and causing discomfort to him via strikes on his communications, supply areas and lines, and his morale. He wrote, "Granted the power to maintain forces by air and direct them by wireless, it is possible to operate regular ground forces for indefinite periods in the heart of enemy occupied territory to the peril of his war machine. The only rational limit to the number of such forces is the air supply potential."2 The troops for his mission should not become engaged with the enemy in the forward area, instead as he put it, "In the back area are his unprotected kidneys, his midriff, his throat, and other vulnerable points."3 The actions of such a force in coordination with the main regular forces he thought would be vital to the success for both. For while weakening the enemy by operating in his rear area, such a force could also start to soak up enemy troops as they were detailed to protect their lines of communications and hunt down their harassers, thus assisting friendly main forces to more easily achieve their objectives. The vastness and difficult terrain that was Burma would aid in success by forcing the enemy to use certain transportation lines for supplies, to stretch their forces out, and provide cover.

Wingate believed a properly trained and supported force could operate for some time deep behind enemy lines against vulnerable and important targets, damaging and causing discomfort to him via strikes on his communications, supply areas and lines, and his morale. He wrote, "Granted the power to maintain forces by air and direct them by wireless, it is possible to operate regular ground forces for indefinite periods in the heart of enemy occupied territory to the peril of his war machine. The only rational limit to the number of such forces is the air supply potential."2 The troops for his mission should not become engaged with the enemy in the forward area, instead as he put it, "In the back area are his unprotected kidneys, his midriff, his throat, and other vulnerable points."3 The actions of such a force in coordination with the main regular forces he thought would be vital to the success for both. For while weakening the enemy by operating in his rear area, such a force could also start to soak up enemy troops as they were detailed to protect their lines of communications and hunt down their harassers, thus assisting friendly main forces to more easily achieve their objectives. The vastness and difficult terrain that was Burma would aid in success by forcing the enemy to use certain transportation lines for supplies, to stretch their forces out, and provide cover.

The new elements of warfare would be linked together and make possible in a deadly combination a force effective & mobile. Mobility as Wingate defined it was the ability to attack when desired and where the enemy would least expect it, and to withdraw into favorable terrain without being successfully pursued. Ground forces would engage in a war of ambush and raiding behind enemy lines, operating without being linked and restrained by conventional & vulnerable landlines of communication. Units would operate in columns small enough to slip past enemy forces, and big enough to inflict damage on defended targets such as supply dumps, roads, bridges, rail lines, waterways. Replacing roads and supply vehicles for the force, aircraft would land in or parachute in supplies. Air power would aid in reconnaissance & when forced to fight with a strong enemy force air power would provide close air support, replacing artillery. Radio contact was to be the tether between the land and air elements, directing the movement of air supplies and ground forces.

Pushing for Action

General Wavell was intrigued by the ideas and impressed by the optimism in which Wingate predicted success. Deciding Wingate should be given the chance to try out his theories with a brigade-size force he gave his official approval and personal backing. Wingate sought out and became a magnet to talented officers willing to think in unorthodox methods. One was Major Michael Calvert from the old Burma Commando school who had led raids during the retreat. He remained impressed by Wingate and his ideas on unconventional warfare since they met. One officer serving on the Joint Planning Staff was Major Bernard Fergusson. While busily working he noticed a, "broad-shouldered, uncouth, almost simian officer who used to drift gloomily into the office for two or three days at a time, audibly dream dreams, and drift out again"4 The only one among the staff there patient enough to listen to Wingate at first, he realized that Wingate was enjoying the attentions of senior officers. Beginning to pay more attention to him, "Soon we had fallen under the spell of his almost hypnotic talk; and by and by we - or some of us - had lost the power of distinguishing between the feasible and fantastic."5 Intrigued by the chance to see action while holding some reservations about his ideas of warfare, Fergusson fell sway to his enthusiastic willingness to bring the fight to the enemy. Like Calvert, he joined up and both were appointed column commanders. Others did too, ignoring the talk and gossip that many (including those not living up to Wingate's standards) were saying that Wingate's ideas were impractical and he himself was unfit for command.

photo caption

Rough terrain of northern Burma. Diseases carried by bacteria & viruses abounded. Casualties from disease and sickness during campaigns in this war theater often easily outnumbered those from battle.

Photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

While Wingate enjoyed Wavell's support, most high-ranking officers in the British Indian Army were opposed to Wingateís idea. They derided the assembling force as, "The Chiefís private army," and Wingate as, "Tarzan."7 The building up of the Indian Army was presenting demands for troops, equipment, and the time to prepare them. Wingate's aggressive & impatient demands for men & equipment for a disparaged force in the face of other pressing needs rubbed many officers

the wrong way.

Wingate saw the Indian Army as well-meaning but training to fight the wrong way, with many officers resenting him, "this person who was trying to teach the Indian Army its job."8 In such a hostile environment, he developed a single-minded determination and, "fanatically pursued his own purpose without regard to any other consideration or purpose."9

Typically, in response to a refusal once to grant him equipment Wingate wrote back harshly, "Inability is a sign of incapability."11

While Wingate enjoyed Wavell's support, most high-ranking officers in the British Indian Army were opposed to Wingateís idea. They derided the assembling force as, "The Chiefís private army," and Wingate as, "Tarzan."7 The building up of the Indian Army was presenting demands for troops, equipment, and the time to prepare them. Wingate's aggressive & impatient demands for men & equipment for a disparaged force in the face of other pressing needs rubbed many officers

the wrong way.

Wingate saw the Indian Army as well-meaning but training to fight the wrong way, with many officers resenting him, "this person who was trying to teach the Indian Army its job."8 In such a hostile environment, he developed a single-minded determination and, "fanatically pursued his own purpose without regard to any other consideration or purpose."9

Typically, in response to a refusal once to grant him equipment Wingate wrote back harshly, "Inability is a sign of incapability."11

photo caption

Chinthe statues next to a Burmese pagoda. Wingate named his force the Chindits, after the Burmese mythical lion, Chinthe. Chindits was the word mispronounced by him from the Burmese word Chinthe. These statues stand by pagodas as guardians.

Photograph courtesy of

Moe Kyaw Thu

Train Hard

By August a training center was established for his embryonic force, given the cover title of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade. He christened his new unit the Chindits, after a Burmese word. With the lack of well-trained troops in India Wingate had to take what was available. The troops were a mixed lot from 3 infantry battalions. One was an unenthusiastic British battalion having never seen action, older than most and used to garrison life & local security defense. Another battalion was a fresh but inexperienced Gurkha unit. Comprised of many new officers who were poorly trained, it was exposed to more senior officers skeptical of Wingate's abilities and Wingate's mission. The third battalion was comprised of veteran soldiers of the Burmese hills tribes (Karen, Kachin and Chin), led by British officers who knew and were comfortable with the land as their troops were. They would become the guides & reconnaissance troops, and Wingate regarded them very highly. Rounding out the force were survivors from the Bush Warfare School for demolitions, RAF signalers, and men training to handle pack animals. Initially disappointed in the quality of troops given to him ("The quality of the existing infantry is bad,"12 he wrote), he set out to prepare them for the brutal reality of jungle travel and combat.

The training worked to build up the fitness and competence of the unit. Loaded with 70-pound packs, men were pushed beyond limits they thought they could endure in the jungle, the fields and in the rains. Long marches and exhaustion were the norm, with those passing out revived & forced to continue. Sickness, minor injuries and heat were inconsequential to the tough standards of Wingate, who believed mind and willpower were the keys to much success. And who was following the same hard training he was ordering his men to do. With wasting time considered an indecency and officers carrying out orders on the run, "Both officers and men cursed Wingate as he drove then through the relentless weeks of exercise, but they admired him, too, and his very eccentricities made him more acceptable: he might be found stark-naked scrubbing himself down with a stiff hairbrush, consuming buffalo milk, or devouring raw onions, the virtues of which he was prepared to preach to all day and sundry."14 Men were taught that the jungle was a friend and that the Japanese were not supermen while fighting in that element. This meant teaching jungle navigation & survival, patrolling, column dispersal, air drops, marksmanship. Troops were trained to ambush the enemy & raid positions. However, Wingate neglected developing swimming skills which were generally lacking in the army.

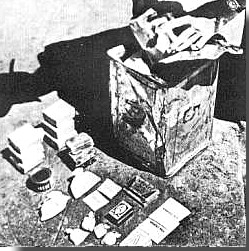

photo caption

Seven days rations for a soldier for the upcoming mission. This included biscuits, cheese, chocolate, meat, powdered milk, salt, sugar, and tea. All together a daily ration weighed only 2 pounds. During the upcoming operation this would prove to be grossly inadequate.

Photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

photo caption

The railway line running north-south in central Burma. This supply line for Japanese forces in northern Burma was the object for Wingate's raid.

Photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

This rigorous training & discipline was essential, for the troops would soon find themselves operating without regular supply or medical aid deep behind enemy lines. It ruthlessly weeded out those not physically or mentally up to the mission. The Burmese battalion was generally fit and in good health. But on the British battalion Wingate commented, "The average Englishman is in general far too apt to take minor ailments too seriously. "16 Attending sick parade without a good cause became a punishable offense, and realizing there would be no easy medical evacuation men learned to look after minor ailments. With the toughening up and recognition that becoming sick meant being left behind to Nature or the Japanese, the sick rate was reduced from some 70% to less than 3%.17 By the end of the training the English battalion had lost close to 33% of its manpower.18 The Gurkha battalion also experienced a similar reduction in manpower. Fresh recruits, though often without adequate training, were brought in to help bring the units up to full strength.

This rigorous training & discipline was essential, for the troops would soon find themselves operating without regular supply or medical aid deep behind enemy lines. It ruthlessly weeded out those not physically or mentally up to the mission. The Burmese battalion was generally fit and in good health. But on the British battalion Wingate commented, "The average Englishman is in general far too apt to take minor ailments too seriously. "16 Attending sick parade without a good cause became a punishable offense, and realizing there would be no easy medical evacuation men learned to look after minor ailments. With the toughening up and recognition that becoming sick meant being left behind to Nature or the Japanese, the sick rate was reduced from some 70% to less than 3%.17 By the end of the training the English battalion had lost close to 33% of its manpower.18 The Gurkha battalion also experienced a similar reduction in manpower. Fresh recruits, though often without adequate training, were brought in to help bring the units up to full strength.

Wingate's assurance, willingness to learn from the Burmese unit, and demonstration for his menís concern created confidence. Sincerity and bluntness in speech commanded the attention of his men and gave the impression, "Wingate belonged to a different and older fashion. When he addressed his men he seemed to speak from a different world."19 To troops he would exalt about the importance of their training, his principles on Long-Range Penetration, and warn them that due to the danger of the mission some would not return alive. Rather then lower morale this increased it. Said one, "It was, I am convinced, the way his undoubted ability came over, and the feeling he gave that here was an honest man whom one could trust, and who would not let one down, if one threw one's lot in with him. "20 To many of his officers Wingate appeared, "An Ancient Mariner in speech, holding his hapless interlocutor with piercing blue eyes and a numbing fund of recondite information, given to harangues, quarrelsome of personality and yet strangely persuasive, he was the perfect image of the unconventional and unorthodox soldier."21 By the time the final exercises ended for the mission, "The men were not much worried. Their faith in Wingate was implicit."22

By 1943 the 77 Indian Brigade numbered 3,000 men, with some 1,000 mules & horses added for transportation of heavy equipment such as weapons and radios.23 The original plan called for the brigade to coordinate as part of a 3-pronged conventional offense to retake central Burma and link up with the Chinese. One prong would see an offense into central Burma from Indian Assam, while another force struck into southern Burma, the Arakan. Another front would be opened up by the Chinese into northern Burma. The Chindits were to cross the dividing line between the British and Japanese forces in central Burma, the River Chindwin. The Chindwin front was lightly held by Japanese outposts and patrols since neither side had the manpower for a strong defense. And having convincingly beaten their enemy a year earlier, the jungle and ridges of central Burma were believed by the Japanese to hinder any large force being deployed and supplied. In 7 separate columns, the Chindits would infiltrate through the jungles & over ridges to head for the Japanese rear. Their operating area was to be the valley containing the railway valley linking Mandalay with Myitkyina, the main north-south supply artery for the Japanese forces in northern Burma. Once there, they were to carry out demolitions to cut this and to harass the enemy.

By 1943 the 77 Indian Brigade numbered 3,000 men, with some 1,000 mules & horses added for transportation of heavy equipment such as weapons and radios.23 The original plan called for the brigade to coordinate as part of a 3-pronged conventional offense to retake central Burma and link up with the Chinese. One prong would see an offense into central Burma from Indian Assam, while another force struck into southern Burma, the Arakan. Another front would be opened up by the Chinese into northern Burma. The Chindits were to cross the dividing line between the British and Japanese forces in central Burma, the River Chindwin. The Chindwin front was lightly held by Japanese outposts and patrols since neither side had the manpower for a strong defense. And having convincingly beaten their enemy a year earlier, the jungle and ridges of central Burma were believed by the Japanese to hinder any large force being deployed and supplied. In 7 separate columns, the Chindits would infiltrate through the jungles & over ridges to head for the Japanese rear. Their operating area was to be the valley containing the railway valley linking Mandalay with Myitkyina, the main north-south supply artery for the Japanese forces in northern Burma. Once there, they were to carry out demolitions to cut this and to harass the enemy.

The Send-Off

Their mission was to be called Operation Longcloth. Then the original offensive plan was halted, the thrust into central Burma canceled by shortages and Chaing Kai-Shek's Chinese from the north backing out. The southern offense along the Arakan coast had already begun back in December. But by February it was bogged down with poor results against a numerically inferior Japanese force. Marked by poor British training, morale and leadership, one report stated, "the seasoned and highly trained Jap troops are confronted by a force which, though impressive on paper, is little better, in a large number of cases, than a rather unwilling band of levies. This cardinal factor, especially in jungle warfare, completely nullifies our estimated 5-3 superiority."25

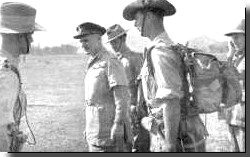

photo caption

Field Marshall Wavell, second from left, inspecting the Chindits before their march into Burma. Wingate is at extreme right, behind Major Fergusson. Rather then accept the farewell salute from the men Wavell initiated it.

Photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

Now a Field Marshall, Wavell had to decide on allowing the Chindits to continue on unsupported. The Japanese not only would be free to concentrate against it, they would have time to repair any damages to their supply lines, which would not be too strained since their forces would not be heavily engaged. His army commander originally supported the endeavor. Now he told Wavell he had to oppose the mission since any experience gained would be out-weighed by the loss from disclosure of introducing such a force without being part of a larger offense, and would create unnecessary casualties. But with his unit physically & psychologically primed, Wingate believed only under combat conditions could the ideas be tested. On February 5th, in a 2-hour meeting with Wavell he argued for the mission. Interested in his ideas & optimistic of its chances, "I had little doubt in my own mind of the proper course, but I had to satisfy myself also that Wingate had no doubts and that the enterprise had a good chance of success and would not be a senseless sacrifice: and I went into Wingate's proposals in some detail before giving the sanction to proceed for which he and his brigade were so anxious."26 Seeing them off the next day at the town of Imphal, Wavell stated to the men, "This is a great adventure. It is not going to be an easy one. I wish you all the very best of luck."27 The Chindits set off for the Chindwin.

1. Trevor Royle, Orde Wingate Irregular Soldier (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1995), 232.

2. Derek Tulloch, Wingate In War And Peace (London: History Book Club, 1972), 62.

3. Tulloch, 63.

4. Bernard Fergusson, Beyond The Chindwin (London: Collins Publishing, 1945), 20.

5. Fergusson, 20.

6. Ibid, 24.

7. Ibid, 21.

8. Michael Calvert, Prisoner of Hope

(London: Jonathan Cape, 1952), 85.

9. Field Marshall William Slim, Defeat Into Victory

(London: Cassell, 1956), 216.

10. Royle, 244.

11. Ibid, 237.

12. Louis Allen, Burma, The Longest War

(New York: St. Martin's Press, 1984), 148.

13. Calvert, 12.

14. Allen, 123.

15. Wilfred Burchett, Wingate's Phantom Army

(London: Frederick Muller, 1946), 44.

16. Allen, 148.

17. Christopher Sykes, Orde Wingate

(New York: World Publishing Company, 1959), 374.

18. Sykes, 372.

19. Ibid, 375.

20. Royle, 241.

21. Allen, 121.

22. Fergusson, 48.

23. Allen, 116.

24. Ibid, 115-16.

25. Ibid, 115.

26. John Connell, Wavell, Supreme Commander

(London: Collins Publishing, 1969), 257

27. Connell, 258.

28. Simon Anglim, "Orde Wingate and the Theory Behind the Chindit Operations: Some Recent Findings," RUSI Journal, Vol. 147, No.2 (April, 2002), 95.