O p e r a t i o n L o n g c l o t h

F i r s t M i s s i o n

F i r s t M i s s i o n

F i r s t M i s s i o n

Across the Chindwin

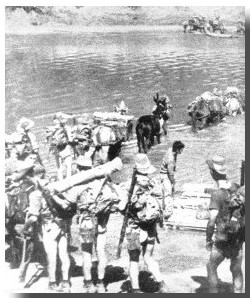

photo caption

Chindits during the Chindwin crossing. Rubber boats and commandeered canoes were used to cross the river whose current at times reached 4 knots.

Photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

Operation Longcloth began as the seven Chindit columns in secrecy headed for the quarter-mile wide Chindwin. Each column numbered the equivalent of around half a battalion (about 400 men), and its combat elements comprised 4 platoons of infantry, and 1 platoon each of engineers, heavy weapons, & reconnaissance. Attached were specialists such as army and RAF radio sections for signaling and for calling in and directing air supply. And to transport the heavy equipment and supplies, 100 mules and 15 horses were attached to each column with their muleteers.1 As part of the overall plan the force was split into two groups. The southern groups of two columns were to function as a diversion, to attract Japanese patrols and to confuse the Japanese as to the direction and intention of the main force. The five columns in the northern group, Wingate’s headquarters with them, were to be the main striking element.

As the troops reached the Chindwin, Wingate's written Order of the Day was distributed to the keyed-up men. Describing it as, "stirring and noble," words of shared sentiment that even made a hardened man burst in tears, Bernard Fergusson would write, "I can imagine no more fitting committal to a great enterprise."3 Making little effort to conceal their movements, on February 14th the southern group of a thousand men crossed the river about 50 miles south of the intended crossing point of the northern group. Proceeding in a southeasterly direction toward the railway, they took an airdrop in broad daylight and strove to create the impression a big force was following them in order to attract Japanese attention. As part of the deception, an officer dressed up as a general and with a large staff proceeded to make demonstrations in a village whose headman was known to be pro-Japanese. The columns marched on independently, heading for hill territory 250 miles beyond the Chindwin & across the major river of the Irrawaddy, to await the arrival of the main force.

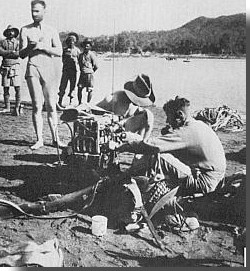

photo caption

Royal Air Force signals team checks their equipment after a river crossing. The air support system created for the Chindits was the best in the theater & in this stage of the war, unique. It had to be for the soldiers had begun Longcloth with only five days of food and water.

Photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

Further north, the main force reached the Chindwin at the village of Tonhe by February 13. That night a small force of Burmese riflemen proceeded ahead in the darkness, crossing unopposed to the opposite bank. The next night rope pulleys were strung across and began ferrying dinghies with heavy equipment. The columns began crossing on dinghies and makeshift rafts, units struggling to finish their passage as quickly as possible. The accompanying mules were coaxed and forced into the fast-flowing river, towed by boat if need be. Men fought the terrified and unruly mules as they kept trying to turn around in midstream, or running off from sight of the water. Come sunset, the columns had not been able to get all their men and animals across. The next morning by the river pandemonium ruled, "a fantastic scene, naked men fighting madly with plunging mules; tiny boats, rocking precariously as shaven-headed little Gurkhas loaded them with precious cargoes of mortars, Bren guns, and rifles; men inflating their rubber dinghies...long lines of mules tethered to trees waiting their turn to cross; and down the mountainside stragglers who had lost their way in the dark hurrying so as not to be left behind."4 After 48 arduous hours all the columns were across & without being discovered by the Japanese.

Further north, the main force reached the Chindwin at the village of Tonhe by February 13. That night a small force of Burmese riflemen proceeded ahead in the darkness, crossing unopposed to the opposite bank. The next night rope pulleys were strung across and began ferrying dinghies with heavy equipment. The columns began crossing on dinghies and makeshift rafts, units struggling to finish their passage as quickly as possible. The accompanying mules were coaxed and forced into the fast-flowing river, towed by boat if need be. Men fought the terrified and unruly mules as they kept trying to turn around in midstream, or running off from sight of the water. Come sunset, the columns had not been able to get all their men and animals across. The next morning by the river pandemonium ruled, "a fantastic scene, naked men fighting madly with plunging mules; tiny boats, rocking precariously as shaven-headed little Gurkhas loaded them with precious cargoes of mortars, Bren guns, and rifles; men inflating their rubber dinghies...long lines of mules tethered to trees waiting their turn to cross; and down the mountainside stragglers who had lost their way in the dark hurrying so as not to be left behind."4 After 48 arduous hours all the columns were across & without being discovered by the Japanese.

photo caption

A supply drop for the Chindits. A drop zone was chosen by the RAF section in either open paddy field or light jungle. Ground signals & smoke, or a fire by night, would be lit in a pattern that could be seen from the air but not as well through the jungle. The drop zone was roughly 600 by 100 yards.41

Photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

Striking

February 18th saw the first clash, by the southern group. Moving forward to strike a Japanese garrison near the Chindwin, Number 1 column under Major Dunlop ran into an enemy patrol. While successfully scattering it, the support section panicked under mortar fire and mules & supplies were lost. Successful in obtain new food from a village, Dunlop continued on to the southeast. He was successful in bridge demolitions near Kyaitkthin, several dozen miles south of where the main force was operating, and then in ambushing a large Japanese unit & killing its commander. The sister column Number 2, was not so fortunate. It reached the railway valley in the area of Kyaitkthin. Marching in daylight next to and then bivouacking a few miles from the railway, it was easily tracked. During the night of March 3rd while it moved out to attack the line it was ambushed. Confusion was intense, and the column commander in the middle of the fight changed the dispersal rendezvous completing unit disorganization. Men were killed & others taken prisoner, and the mules and heavy weapons were lost. Later analyzing, Wingate saw how the commander had failed to observe the philosophy behind the mission and instead was thinking too conventional, "The disaster to No.2 column was easily avoidable and would never have taken place had the commander concerned understood the doctrines of penetration."5 While some survivors headed back to friendly lines, others met up with Number 1 column heading towards the Irrawaddy River.

February 18th saw the first clash, by the southern group. Moving forward to strike a Japanese garrison near the Chindwin, Number 1 column under Major Dunlop ran into an enemy patrol. While successfully scattering it, the support section panicked under mortar fire and mules & supplies were lost. Successful in obtain new food from a village, Dunlop continued on to the southeast. He was successful in bridge demolitions near Kyaitkthin, several dozen miles south of where the main force was operating, and then in ambushing a large Japanese unit & killing its commander. The sister column Number 2, was not so fortunate. It reached the railway valley in the area of Kyaitkthin. Marching in daylight next to and then bivouacking a few miles from the railway, it was easily tracked. During the night of March 3rd while it moved out to attack the line it was ambushed. Confusion was intense, and the column commander in the middle of the fight changed the dispersal rendezvous completing unit disorganization. Men were killed & others taken prisoner, and the mules and heavy weapons were lost. Later analyzing, Wingate saw how the commander had failed to observe the philosophy behind the mission and instead was thinking too conventional, "The disaster to No.2 column was easily avoidable and would never have taken place had the commander concerned understood the doctrines of penetration."5 While some survivors headed back to friendly lines, others met up with Number 1 column heading towards the Irrawaddy River.

After the Chindwin the main northern group of five columns set off eastward, Calvert's column leading a day ahead. The men plunged into the jungles and unmarked swamps carrying 72-pound packs, while the muleteers struggled to get their animals over the steep and plunging ridges of the Zibyu Range. It took the northern group 4 days to reach a point 10 miles east of their crossing where they took their first supply drop of nearly 70,000 pounds.6 Over the mountain range they marched and climbed on, their path through the jungle now aided now by a little-known trail allowing single-file movement after some hacking out. The columns reached an escarpment then plunged into a pleasant river valley of teak forest. As the going was becoming easier for a while, and as there was no sign of combat (small Japanese patrols were finding but avoiding the Chindits) the men began to relax. The loss of discipline infuriated Wingate. He harangued officers if he felt that march or noise discipline was lax, "Whenever the opportunity occurred, in the course of the approach march to the railway I personally lectured all officers."8

photo caption

RAF signalman of one of the columns. The RAF radio 1082/3 set was bulky at some 200 pounds, and it required several mules to transport it. RAF Squadron Leader Robert Thompson commanded the RAF detachments. He would rise to later fame during the Cold War as an expert on counter-insurgency warfare, special adviser to various governments on South-East Asia

Photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

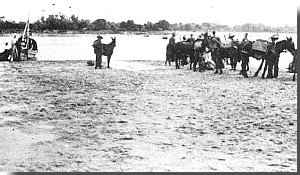

photo caption

A Chindit column crossing a river early on in the campaign with their mules. The mules were a vital element for they carried the heavy weapons and their ammunition, the important radios & their batteries and charging machinery for them.

Photograph courtesy of

Her Majesty's Stationary

Office, U.K.

After several weeks of marching some 100 miles (by map), by March they had reached the railway valley. Wingate's plan called for three columns to be detached for the purpose of diverting attention and enemy movement away from the valley. Numbers 7 and 8 columns were to strike the Japanese garrison at Pinlebu 30 miles west of the railway. Number 4 column was to ambush the road north from Pinlebu to the town of Pinbon. The two columns put in quick attacks against Pinlebu aided by an air attack, suffering light casualties. They were successful, as Japanese forces moved up from the area of the railway to counter this threat. Early in the morning of March 4th Number 4 column while in the midst of crossing a river on the way to its position near Pinbon was attacked. The Japanese split the force, some men were lost while others panicked their first time in combat. After rallying by its commander at the rendezvous point, the force had to beat off a second attack. Realizing with the heavy weapons & radios lost from the stampeded mules, the commander decided that to continue on was useless. He dispersed the unit and most made it back to the Chindwin.

After several weeks of marching some 100 miles (by map), by March they had reached the railway valley. Wingate's plan called for three columns to be detached for the purpose of diverting attention and enemy movement away from the valley. Numbers 7 and 8 columns were to strike the Japanese garrison at Pinlebu 30 miles west of the railway. Number 4 column was to ambush the road north from Pinlebu to the town of Pinbon. The two columns put in quick attacks against Pinlebu aided by an air attack, suffering light casualties. They were successful, as Japanese forces moved up from the area of the railway to counter this threat. Early in the morning of March 4th Number 4 column while in the midst of crossing a river on the way to its position near Pinbon was attacked. The Japanese split the force, some men were lost while others panicked their first time in combat. After rallying by its commander at the rendezvous point, the force had to beat off a second attack. Realizing with the heavy weapons & radios lost from the stampeded mules, the commander decided that to continue on was useless. He dispersed the unit and most made it back to the Chindwin.

These actions left a path for the remaining two columns, numbers 3 and 5 led by Calvert and Fergusson respectively, to march unobserved to the target and strike. Calvert deployed his force on March 6th to Nankan railway station, just miles north of Wuntho, and set to work. Explosions from the demolition parties reverberated for miles as a happy Calvert celebrated his 30th birthday. Calvert had set up two blocking parties north and south of the station. From the south a Japanese truck convoy approached and was met by a hail of fire from the Gurkhas. Japanese reinforcements rushed to respond, and soon the blocking party was outnumbered. Appearing with more men, Calvert led them in a counter-attack. Heavy casualties were inflicted upon the Japanese who withdrew, while Chindit casualties were zero.

The same day 10 miles further north Fergusson's men of Number 5 column began their mining. The place was were the rail line ran through a gorge, and demolitions were set on the bridge as well as the gorge. With the explosions, "The mules plunged and kicked, the hills for miles around rolled the noise of it about their hollows and flung it to their neighbors."9 A blocking patrol ran into a patrol of Japanese in a village and lost several dead and wounded. With a half-dozen badly wounded unfit to move, "The problem we had all so long dreaded had at last arisen."10 The wounded had to be left behind by Fergusson. Together, both columns had sabotaged the line in over 70 places, with bridges destroyed and roads mined.

It was 3 days after the crossing that reports began arriving into Japanese headquarters of two large forces infiltrating eastward. At first the Japanese were not too concerned with the British force that they believed was just a small raiding force. As unclear and conflicting reports filtered in, only several battalions were initially sent to hunt down and destroy them. It was difficult to get good intelligence on the size and movements of the British, let alone determine their objectives. The British the force was splitting into individual columns and kept on the move by Wingate to avoid being pinned down. The successful actions against the two columns deep inside their territory in early March along with prisoner interrogations awoke the Japanese command to the threat. And also to the surprising realization that contrary to earlier belief, this was a large force infiltrating through their territory and that it was being supplied not by land but by air. Japanese

Burma Army command

ordered the two infantry divisions covering north & central Burma to destroy this British force. As Wingate made the decision to continue deeper into Japanese territory, the problems he faced increased.

It was 3 days after the crossing that reports began arriving into Japanese headquarters of two large forces infiltrating eastward. At first the Japanese were not too concerned with the British force that they believed was just a small raiding force. As unclear and conflicting reports filtered in, only several battalions were initially sent to hunt down and destroy them. It was difficult to get good intelligence on the size and movements of the British, let alone determine their objectives. The British the force was splitting into individual columns and kept on the move by Wingate to avoid being pinned down. The successful actions against the two columns deep inside their territory in early March along with prisoner interrogations awoke the Japanese command to the threat. And also to the surprising realization that contrary to earlier belief, this was a large force infiltrating through their territory and that it was being supplied not by land but by air. Japanese

Burma Army command

ordered the two infantry divisions covering north & central Burma to destroy this British force. As Wingate made the decision to continue deeper into Japanese territory, the problems he faced increased.

photo caption

Men and mules at the Irrawaddy. Crossing the Irrawaddy was to be Wingate's most controversial decision of the campaign.

Photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

Across the Irrawaddy

In the hills northwest of Nankan Station, Wingate was contemplating either using the nearby hills as a secure base for raiding sorties, or crossing the Irrawaddy River for deeper raids in land with friendly Kachin tribe people. Then on March 8 after being out of radio contact for several weeks, Dunlop & the southern group headquarters were able to make radio contact with brigade headquarters. They informed Wingate they had safely crossed the Irrawaddy some 40 miles south of where his headquarters were at. Wingate consulted Calvert and Fergusson, the commanders closest to the river for their opinion. A few dozen miles from the river and confident from their success, both were keen on proceeding eastward. Having enjoyed success so far and wanting to continue his experiment with long-range penetration, after much thought Wingate decided to order the Chindits across the mile-wide Irrawaddy.

Sending a patrol ahead, Fergusson’s column was

the first to reach

the Irrawaddy at Tigyaing on March 10. Fergusson's men entered the river town to a warm reception, the population friendly and providing aid in acquiring boats. The Japanese arrived as the last of the boats were crossing, the stubborn mules delaying the completing of the afternoon crossings till dusk, and Fergusson was just hauled aboard as shots were ringing out. Calvert was pursued continuously to the river, his engineer platoon leaving booby traps in their wake. Just downstream of where Fergusson had crossed and a few days later, the column was attacked as it attempted to cross. Calvert re-organized his pressed rearguard to hold off the Japanese as the men labored with an inadequate number of rafts and stubborn mules. Then Calvert commandeered some boats which at that moment by chance were coming up the river. While having to leave behind a few dead & wounded,

the column was able to cross under fire. Further north at Inywa, Wingate leading the other columns sent Burmese soldiers across to scout first. They met a friendly reception from civilians who agreed to provide food and boats. By March 18th the entire force was across and enjoyed a very big supply drop.

the column was able to cross under fire. Further north at Inywa, Wingate leading the other columns sent Burmese soldiers across to scout first. They met a friendly reception from civilians who agreed to provide food and boats. By March 18th the entire force was across and enjoyed a very big supply drop.

photo caption

Supply drop. RAF pilots & radio operators were manning ground radios using their air force experience to talk directly to aircraft for guiding in supply drops. The RAF personnel were volunteers who underwent the same rigorous training the Chindits did.

Photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

With Calvert sent to the south to blow up a viaduct on the Mandalay-Lashio road, the rest of the force rested for several days. The Chindits were now over 150 miles behind Japanese lines. The increased range was making it difficult for aircraft to undertake supply drops. The terrain east of the river was also more open, with more motorable roads and with much waterless forest. Here the force found itself concentrated in a watery triangle loop formed by the Irrawaddy to the west, and its branch to the northeast, the Shweli River. With the southern group meeting up, the Chindit columns were within 15 miles of one another constricted inside the river loop.14 This was making it easier for the Japanese to deploy their two divisions, with elements of a third arriving, into blocking positions along the rivers and the land part of the triangle base. They commandeered local boats, patrolled expected crossing sites, and motorized units sent in from the south.

The unfavorable terrain and the large Japanese force began to have an effect. The columns were beginning to be plotted more accurately now. Some struggled to stay only several hours ahead of pursuing Japanese forces while hurriedly collecting supplies from airdrops. Privation multiplied as air supply became more difficult. A day's ration of biscuits, cheese, dates, supplemented by chocolate and tea left men hungry, "The ration was devised in Delhi and intended for parachute raids of three days duration only. It was totally inadequate for a prolonged operation such as ours."16 Patrols had to be cautious about foraging in villages in case of Japanese patrols. Men dug in dry riverbeds and waterholes for brownish water and went hungry for food. The heat and exhaustion from marching and fighting was sapping the energy of the force, "At this period a number of officers and men showed signs of losing their physical fitness and energy and the...marches had strained them to the utmost."17 The Burmese hill tribesmen serving with the recon units were invaluable in their familiarity with the land & people. They became the source for information on Japanese movements, on village rice for food, and knowing where to look for water in the dry, flat land.

In order to retain mobility & because they did not have the facilities, back in India Wingate had established a policy of leaving behind the more seriously wounded. Now the wounded took their chances hoping they would survive without quick care, that villagers would not turn them into the Japanese, that the enemy would not butcher them. The Japanese had a different military culture with a harsh ideology toward prisoners and regularly committed atrocities. Most prisoners already weakened by their ordeal would not survive captivity. As casualties were left behind their fate would begin to gnaw at the others and, "This was the stark moment when fear planted its first seed. And as the men grew weaker because of the shortage of food and water and the punishing toll from the exhausting march across the Dry Zone, the seed was nourished until it eventually blossomed into open fear when the orders were eventually given to return to India on a journey fraught with fear."18

In order to retain mobility & because they did not have the facilities, back in India Wingate had established a policy of leaving behind the more seriously wounded. Now the wounded took their chances hoping they would survive without quick care, that villagers would not turn them into the Japanese, that the enemy would not butcher them. The Japanese had a different military culture with a harsh ideology toward prisoners and regularly committed atrocities. Most prisoners already weakened by their ordeal would not survive captivity. As casualties were left behind their fate would begin to gnaw at the others and, "This was the stark moment when fear planted its first seed. And as the men grew weaker because of the shortage of food and water and the punishing toll from the exhausting march across the Dry Zone, the seed was nourished until it eventually blossomed into open fear when the orders were eventually given to return to India on a journey fraught with fear."18

photo caption

C-47 transport aircraft, one of the two types of transports used to supply the Chindits. Elements of two air transport squadrons only were allotted to the Chindit mission, for a total of only 6 aircraft, and would carry out 175 supply sorties.42

Photograph courtesy USAF

The Deadly Return

Recognizing it was becoming imperative to return, on the 24th of March Wingate was ordered to end the mission and return to India. On the 26th Wingate held a conference of his senior officers and he argued that having accomplished their objectives it was important to bring home as many men with experience as possible. He proposed the columns should break up, each free to choose their own way back to friendly lines. This would make it easier to slip past the strong Japanese forces gathering along the Irrawaddy and Shweli. Before re-crossing the Irrawaddy the heavy weapons and animals were to be abandoned to increase speed, and false supply drops would be laid to the south to throw off pursuit. The distance from airbases would make supply of a large force moving together impossible he claimed, and to march through friendly population to the northeast as part of a wide sweep back would be to move out of air range. Unsuccessfully, Fergusson argued for keeping the brigade together to make it easier to fight through opposition, and to move east across the Shweli and then loop around to north.

Desperate for supplies, a final large air drop was organized on the paddy fields near Japanese-occupied Baw. Blocking parties were sent secretly to the outskirts of the village in case the enemy discovered the drop and tried to interfere. But a tired officer to a shortcut to his assigned position and moved through the village outskirts, triggering Japanese fire. Fighting lasted for several hours as the Chindits took heavy casualties in trying to clear the Japanese. The airdrop was cut short and most supplies were not recovered. The officer in question was broken in rank and sent to another column. The desperate and unusual circumstances demanded unique solutions to discipline, and did

occasionally happen again.

Desperate for supplies, a final large air drop was organized on the paddy fields near Japanese-occupied Baw. Blocking parties were sent secretly to the outskirts of the village in case the enemy discovered the drop and tried to interfere. But a tired officer to a shortcut to his assigned position and moved through the village outskirts, triggering Japanese fire. Fighting lasted for several hours as the Chindits took heavy casualties in trying to clear the Japanese. The airdrop was cut short and most supplies were not recovered. The officer in question was broken in rank and sent to another column. The desperate and unusual circumstances demanded unique solutions to discipline, and did

occasionally happen again.

photo caption

Bernard Fergusson. A former aide to Field Marshall Wavell, this Scottish soldier had briefly met Wingate while both of them were stationed in Palestine. In case he did not return, Fergusson made several of his officers memorize an argument to present to Wavell in which he recommended a future type of operation as this was worthwhile even if it ended in disaster.

Photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

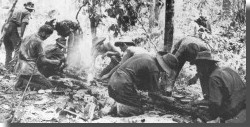

photo caption

Chindit column preparing for a meal. At night bivouacking in the jungle away from trails, it was safe to light fires for visibility was limited to several dozen meters.

Photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

Brigade headquarters with Number 7 column tried initially to cross the Irrawaddy on March 29th at the same spot they had come across, at Inywa. The initial attempt at dawn in rubber boats was aborted in the face of Japanese fire. With enemy reinforcements arriving on the other side Wingate decided against risking the force by making an opposed river crossing, though leaving some men already across stranded. Keeping his own counsel Wingate gloomily admitted, "At that moment, I must confess it seemed to me that the enemy stood an excellent chance of pinning the force down before it could disperse, and I do not think that I exerted myself sufficiently to instill the necessary confidence into my subordinates."22 While the party from Number 7 column already across desperately tried to slip through the Japanese, the remaining half with Number 8 column dispersed into small groups and turned north and east. Wingate dispersed his brigade headquarters group of some 200 men into 5 groups. He rested them in the forest for a week before attempting the Irrawaddy, receiving final supplies by air and eating mule meat.

As the rearguard, Fergusson's column tried to lead diversions away from the main force, creating false camps and trails. Several skirmishes developed, but while causing the Japanese confusion, they also fell behind the main group. With his radio set having been lost in a night clash with the Japanese, Fergusson could neither call for air drops nor pick up the trail of Wingate's group as it skillfully covered its tracks. Trailing behind Fergusson noticed, "Wingate's uncanny instinct for cross-country marching - his sense of watersheds, good gradients, thinner jungle and so forth-was apparent."24 The column reached the fast-flowing Shweli River on March 30th. With only two small boats and Japanese nearby Fergusson waited till night. The crossing was, "There is no word for it but nightmare. The roaring of the waters, the blackness of the night, the occasional sucking of a quicksand were bad enough, but the current was devilish."25 As the boats could only ferry two at a time, parties of men linked together began to wade across, to the cries of those being swept away. One boat was swamped and the other with its Burmese pilot abandoned them. Struggling up sandy cliffs, they realized instead of having crossed over to the other side they had only made it halfway across, to a sandbank. The men were cold and tired, hungry and on edge. Fergusson led many into the water to the far bank, but the non-swimmers refused to cross in spite of being ordering to do so. With dawn coming and knowing the Japanese would too, Fergusson decided he could not risk staying and had to move on with the men he had. With only 74 men with him, leaving some 46 behind on the sandbank or drowned, "The crossing of the Shweli River will haunt me all my life; and to my mind the decision which fell to me there was a cruel as any which could fall on the shoulders of a junior commander."26 Short on food & unable to get a supply drop, the survivors struggled on toward the northwest.

As the rearguard, Fergusson's column tried to lead diversions away from the main force, creating false camps and trails. Several skirmishes developed, but while causing the Japanese confusion, they also fell behind the main group. With his radio set having been lost in a night clash with the Japanese, Fergusson could neither call for air drops nor pick up the trail of Wingate's group as it skillfully covered its tracks. Trailing behind Fergusson noticed, "Wingate's uncanny instinct for cross-country marching - his sense of watersheds, good gradients, thinner jungle and so forth-was apparent."24 The column reached the fast-flowing Shweli River on March 30th. With only two small boats and Japanese nearby Fergusson waited till night. The crossing was, "There is no word for it but nightmare. The roaring of the waters, the blackness of the night, the occasional sucking of a quicksand were bad enough, but the current was devilish."25 As the boats could only ferry two at a time, parties of men linked together began to wade across, to the cries of those being swept away. One boat was swamped and the other with its Burmese pilot abandoned them. Struggling up sandy cliffs, they realized instead of having crossed over to the other side they had only made it halfway across, to a sandbank. The men were cold and tired, hungry and on edge. Fergusson led many into the water to the far bank, but the non-swimmers refused to cross in spite of being ordering to do so. With dawn coming and knowing the Japanese would too, Fergusson decided he could not risk staying and had to move on with the men he had. With only 74 men with him, leaving some 46 behind on the sandbank or drowned, "The crossing of the Shweli River will haunt me all my life; and to my mind the decision which fell to me there was a cruel as any which could fall on the shoulders of a junior commander."26 Short on food & unable to get a supply drop, the survivors struggled on toward the northwest.

Calvert had earlier been ordered by Wingate to head south to take out the Gokteik Viaduct on the important Mandalay-Lashio road. Learning of Japanese patrols in the area they were moving into, he set up a large ambush. On the 23rd of March advance elements of a Japanese battalion walked into their trap, and for the loss of a single man they killed a hundred Japanese in this their 12th engagement.27 He was disappointed upon receiving Wingate’s order to take his column home two days later. Number 3 column headed north as fast as they could, leaving behind booby traps to slow their pursuers. Attempting to organize a crossing of the Shweli, they encountered Japanese resistance. Withdrawing back into the jungle, the morale of the tired unit appeared to be shaken. Calvert was urged by his subordinate officers to break up the unit into small groups of around 40. This they argued would create more chances of finding boats and slipping through the Japanese. Going along, Calvert issued careful orders to stay safe and radioed for a final supply drop. Eight days worth of food plus new boots floated down, which had to last the men for their trip 350 miles to British lines. After crossing the Irrawaddy Calvert's group came across the railway line again. His demolitions officer remembered, "I was all for leaving sleeping dogs lie and getting across as quickly as possible, but not Calvert."29 Not willing to let a good opportunity slip away, Calvert placed time charges on the railway with his last explosives.

The march back became an ordeal of survival as the Chindits maneuvered to escape the Japanese and make their way to the Chindwin. Facing supply problems as many of the radios had been abandoned with the mules, airdrops for food and water became very rare. Stress from combat with a numerically superior enemy behind his lines and having to dodge their patrols increased the mental strain. With little sleep and on the run, fear and exhaustion put men's nerves on edge, competing with hunger and thirst. Fergusson experienced hallucinations about sugar, the craving for which was driving men into further agony. Men and commanders fought to retain some hope against the feeling of being constantly hunted and tired, against the paranoid feeling of enemy omniscience to retain spirit. As one young officer wrote on remaining disciplined soldiers,

"few of them were prepared to look for trouble at this stage, many of them committing acts or taking decisions which they would possibly be ashamed of or regret for the rest of their lives. Acts of physically exhausted, starving, thirsty, mentally shaken men, acts which anyone who was not there is in no position to criticize, because there is no way an outsider could possibly understand, or even know with any certainty that he would have acted differently."30

The march back became an ordeal of survival as the Chindits maneuvered to escape the Japanese and make their way to the Chindwin. Facing supply problems as many of the radios had been abandoned with the mules, airdrops for food and water became very rare. Stress from combat with a numerically superior enemy behind his lines and having to dodge their patrols increased the mental strain. With little sleep and on the run, fear and exhaustion put men's nerves on edge, competing with hunger and thirst. Fergusson experienced hallucinations about sugar, the craving for which was driving men into further agony. Men and commanders fought to retain some hope against the feeling of being constantly hunted and tired, against the paranoid feeling of enemy omniscience to retain spirit. As one young officer wrote on remaining disciplined soldiers,

"few of them were prepared to look for trouble at this stage, many of them committing acts or taking decisions which they would possibly be ashamed of or regret for the rest of their lives. Acts of physically exhausted, starving, thirsty, mentally shaken men, acts which anyone who was not there is in no position to criticize, because there is no way an outsider could possibly understand, or even know with any certainty that he would have acted differently."30

photo caption

Message marked in clearing by a party. A number 8 column party used this to signal for an aircraft to remove them. A C-47 landed to make a medical evacuation of sick & wounded, enabling rest to march to safety at faster pace.

Photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

Their physical state was deteriorating. The men endured eating small animals & plants on the recommendations of their Burmese hill tribesmen. The Japanese practice of stationing troops near villages knowing the Chindits would seek them out for food increased the risks. Dispersal groups were forced to break into smaller parties in the quest for food, and unexpected engagements were fought at close-quarters breaking them up further into smaller clusters and individuals. As they sought food and escape, in some cases men only survived due to the aid of friendly villagers. Individuals faced the conflict of not knowing if the villagers they desperately turned to for food would afterwards let the pursuing Japanese know of their presence. Diseases such as malaria & malnutrition appeared while insects such as lice and leeches added to the misery. Short on energy they pushed on, the jungle ripping at their uniforms and skin, men becoming stragglers hobbled by disease or wounds. Said one with Calvert's party on the hazards to overcome, "For the last eleven days of the march I had nothing to eat except two handfuls of buffalo liver and a few jungle roots. During the last few days I was taking ten to twelve Benzedrine tablets a day, and it was only these that kept me going."32

Across To Safety

Evading pursuers and posts set up along the rivers, in late April small parties began reaching the Chindwin. Calvert's dispersal group was the first across on the 15th. Fergusson's men struggled back in small groups with friendly Kachin villagers providing food and directions, though only 33% of his 318 men he had taken into Burma with him survived.33 A dispersal party each from Number 7 and 8 columns reached the remote British outpost of Fort Hertz in the extreme far north in mid-May. Half of Number 7 column crossed the Shweli River, harassed by the Japanese. They headed east toward China, swelling in numbers by a few men of Fergusson's who had become separated. Friendly Kachin villagers aided them with food and information. After a harrowing journey and fighting off Japanese, on May 1st they made contact with the Chinese army in southern Yunnan province. Taking a long time to cross one river due to the lack of boats, the men from the southern column were ambushed once across on the other side. Split up into tiny exhausted groups, most were hunted down or died alone in the forest. Only about 25% from the southern group made it safely back.34

Evading pursuers and posts set up along the rivers, in late April small parties began reaching the Chindwin. Calvert's dispersal group was the first across on the 15th. Fergusson's men struggled back in small groups with friendly Kachin villagers providing food and directions, though only 33% of his 318 men he had taken into Burma with him survived.33 A dispersal party each from Number 7 and 8 columns reached the remote British outpost of Fort Hertz in the extreme far north in mid-May. Half of Number 7 column crossed the Shweli River, harassed by the Japanese. They headed east toward China, swelling in numbers by a few men of Fergusson's who had become separated. Friendly Kachin villagers aided them with food and information. After a harrowing journey and fighting off Japanese, on May 1st they made contact with the Chinese army in southern Yunnan province. Taking a long time to cross one river due to the lack of boats, the men from the southern column were ambushed once across on the other side. Split up into tiny exhausted groups, most were hunted down or died alone in the forest. Only about 25% from the southern group made it safely back.34

Wingate led his group back, trying to ensure no one dropped out. He, "marched at the head of this column with his revolver, rifle, and jungle knife, just like the rest of us."35 They crossed the railway only hours ahead of the Japanese patrols. Showing his devotion, Wingate halted the group for 2 days to try to let one member sick with diarrhea try to unsuccessfully recuperate his strength. Another sick man who had trouble keeping up let himself fall behind rather than jeopardize the group by slowing them down. Their failing rations were supplemented by eating wildlife and roots. Wingate's party fruitlessly tried to buy food from a village. As they were leaving, an old Buddhist hermit ran after them saying his holy destiny was to help a group of strangers whom he had been forewarned about. He guided the depleted group through remote paths & streams, and over the Zibyu to within sight of the Chindwin. Finally, on the 26th of April they spotted the river. After spending nearly half of the daylight hours making their way through thick elephant grass and avoiding a Japanese patrol, the cut-up and bleeding party arrived at the river bank. A group of the best swimmers with Wingate crossed the next day and made contact with friendly forces, bringing the remaining collection across in boats a day later under fire. Wingate’s party was one of only two out of the five headquarters groups to make it back. Individuals continued to straggle across into early June.

photo caption

Wingate meeting with some of his officers after the mission. While with the hermit Wingate's party caught a turtle for food. Before leaving them the hermit asked for the turtle in return for the help. For luck he prayed over it & then released it into the water.

Photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

Of the 3,000 men of the first Chindit expedition, only 2,182 had returned, and without their heavy weapons and animals.36 Some 120 of the Burmese hill tribesmen had been allowed to return to their home villages.37 Of the remaining number, around 450 had died in action and most of the rest being taken prisoner.38 The survivors were skin and bones from serious weight loss and riddled with ailments such as dysentery, malaria and beriberi. Many were so debilitated that only 600 were fit to see combat again in the war.39 In a February interview before the operation Wingate said, "If this operation succeeds, it will save thousands of lives. Should we fail, most of us will never be heard from again. If we succeed, we shall have demonstrated a new style of warfare to the world, bested the Jap at his own game, and brought nearer the day when the Japanese will be thrown bag and baggage out of Burma."40 Longcloth, he hoped, would be the start.

Of the 3,000 men of the first Chindit expedition, only 2,182 had returned, and without their heavy weapons and animals.36 Some 120 of the Burmese hill tribesmen had been allowed to return to their home villages.37 Of the remaining number, around 450 had died in action and most of the rest being taken prisoner.38 The survivors were skin and bones from serious weight loss and riddled with ailments such as dysentery, malaria and beriberi. Many were so debilitated that only 600 were fit to see combat again in the war.39 In a February interview before the operation Wingate said, "If this operation succeeds, it will save thousands of lives. Should we fail, most of us will never be heard from again. If we succeed, we shall have demonstrated a new style of warfare to the world, bested the Jap at his own game, and brought nearer the day when the Japanese will be thrown bag and baggage out of Burma."40 Longcloth, he hoped, would be the start.

1. Derek Tulloch, Wingate In War And Peace (London: History Book Club, 1972), 63.

2. Tulloch, 76-7.

3. Bernard Fergusson, Beyond The Chindwin (London: Collins Publishing, 1945), 59.

4. Christopher Sykes, Orde Wingate

(New York: World Publishing Company, 1959), 390.

5. Louis Allen, Burma, The Longest War

(New York: St. Martin's Press, 1984), 129.

6. Allen, 128.

7. Harold James, Across The Threshold of Battle

(Lewis: The Book Guild, 1993), 76.

8. Sykes, 393.

9. Fergusson, 99.

10. Ibid, 96.

11. General R. Mutaguchi in Tulloch, 93.

12. Trevor Royle, Orde Wingate Irregular Soldier (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1995), 251.

13. Fergusson, 76.

14. Sykes, 412.

15. Fergusson, 127.

16. Then Lieutenant Jeffrey Lockett in Tulloch, 83.

17. Sykes, 412.

18. James, 114.

19. Fergusson, 145.

20. Royle, 254.

21. Fergusson, 92.

22. Sykes, 419.

23. Ibid, 422.

24. Fergusson, 144.

25. Ibid, 171.

26. Ibid, 174-75.

27. Sykes, 415.

28. James, 157.

29. Lockett in Tulloch, 87.

30. James, 177.

31. Allen, 143.

32. Lockett in Tulloch, 87.

33. Allen, 142.

34. Sykes, 432.

35. Royle, 252.

36. Sykes, 432.

37. Allen, 147.

38. Ibid, 147.

39. Sykes, 432.

40. Wilfred Burchett, Wingate's Phantom Army (London: Frederick Muller, 1946), 179.

41. Ibid, 234.

42. Ibid, 234.