O p e r a t i o n T h u r s d a y

S e c o n d M i s s i o n

S e c o n d M i s s i o n

S e c o n d M i s s i o n

Flying In

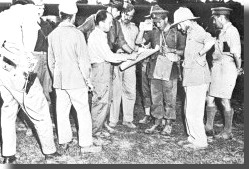

photo caption

Airfield scene where officers are shown the photograph of the Piccadilly block. Behind Wingate is Tulloch, in front Calvert. Next to him RAF Marshall Baldwin, Colonel Scott who would command a column in first wave, then Allison.

U.S. Air Force photo

On the evening of March 5th, gliders stood ready to pair up with their tows and men began grouping up into loads for the airborne stage of Operation Thursday. Aircraft from both RAF and USAAF squadrons were ready at several airfields. But less than an hour before take-off the plan had to be quickly amended. A photograph taken on a last minute flight by an aircraft over landing zone Piccadilly was rushed to Wingate and Cochran. It showed Piccadilly to be unusable, covered by teak logs laid out by Burmese villages for drying out before use. Believing flyovers of the landing areas might tip off the Japanese, Wingate had refused permission for high-level air reconnaissance in the last weeks before the start of the mission. He also failed to employ specialized ground reconnaissance units. Cochran at the last minute had ordered an unauthorized fly-over. There were tense moments of discussion between Wingate, Calvert and Cochrane about if the plan had been compromised or not and if delay meant giving up the benefits of the good moon. The operation was hurriedly altered. The number of landing zones was reduced to two, and Calvert's entire brigade along with some columns of 111th Brigade would be flown into Broadway. Calvert preferred the slower build-up with just one landing zone over splitting his brigade up both sides of the Irrawaddy. With Cochran quickly re-briefing the pilots, Calvert gave orders for a change over of loads and passengers into the 61 gliders that would go into Broadway.

Just over an hour behind schedule, the first wave of aircraft rose from their Indian airfield into the fading light. The tow planes in the dark led their gliders on a journey 270 miles eastward and behind enemy lines to deposit their cargo. Each transport towed a pair of gliders, to compensate for the shortage of experienced glider pilots and to get as many men in as possible. Overloaded by soldiers who had stored extra supplies onboard, some with terrified mules or jeeps onboard, the gliders were pulled struggling over mountaintops. Climbing to 8,000 feet to clear the mountains they encountered air turbulence. Together with the overloading of the gliders, this caused some tow lines to begin to snap under the strain. The rest of the air train proceeded onward. By the brilliant moonlight the first wave with Calvert and Allison (deputy commander of the Air Commandos) onboard could see Broadway as they approached.

photo caption

A transport tug with its glider. Turbulent air and heavy gliders meant that of the 61 gliders launched to Broadway only 37 made it. Of the others, 8 were recalled, 10 broke loose after take-off and landed on the British side of the Chindwin, and 6 landed among the Japanese between the Chindwin & Broadway.37

U.S. Air Force photo

The first gliders landed in the clearing and the men spilled out into the tall elephant grass. Surprise had been achieved, there was no Japanese opposition. While some soldiers established perimeters around the clearing, others with Calvert & Allison struggled to get landing lights set up and gliders moved out of the way for the later waves. An unseen obstacle of several ruts was causing landing accidents and casualties. The landing zone was becoming unusable, gliders piling up into those previously damaged by the ruts that could not be manhandled out of the way in time. There was a halt in landings, "The crescendo of gliders and tumult reached its peak and died down. The first wave had landed."1 Calvert was becoming exhausted and dispirited, and so ordered a temporary halt to subsequent landings until the mess could be straightened out. Back in India, senior commanders waiting in suspense turned apprehensive as the radio silence gave way to the code word given out by Calvert to stop landings. Without knowing the reasons, Wingate & the others could only

guess despondently

the operation was failing while struggling to remain patient & await further word. Through the night into the morning, soldiers with spades & American engineers with a bulldozer & scrapper toiled to fill in ditches, clear away wrecked gliders, to flatten out landing strip 5,000 feet long. After dawn the next day, Calvert sent a coded message back to India stating Broadway would be ready for flights that night.

The first gliders landed in the clearing and the men spilled out into the tall elephant grass. Surprise had been achieved, there was no Japanese opposition. While some soldiers established perimeters around the clearing, others with Calvert & Allison struggled to get landing lights set up and gliders moved out of the way for the later waves. An unseen obstacle of several ruts was causing landing accidents and casualties. The landing zone was becoming unusable, gliders piling up into those previously damaged by the ruts that could not be manhandled out of the way in time. There was a halt in landings, "The crescendo of gliders and tumult reached its peak and died down. The first wave had landed."1 Calvert was becoming exhausted and dispirited, and so ordered a temporary halt to subsequent landings until the mess could be straightened out. Back in India, senior commanders waiting in suspense turned apprehensive as the radio silence gave way to the code word given out by Calvert to stop landings. Without knowing the reasons, Wingate & the others could only

guess despondently

the operation was failing while struggling to remain patient & await further word. Through the night into the morning, soldiers with spades & American engineers with a bulldozer & scrapper toiled to fill in ditches, clear away wrecked gliders, to flatten out landing strip 5,000 feet long. After dawn the next day, Calvert sent a coded message back to India stating Broadway would be ready for flights that night.

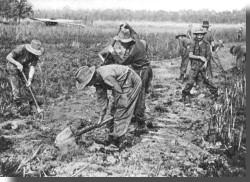

photo caption

Chindits at Broadway work to extend the airstrip. Casualties on the landing had been 51 dead and wounded, but the runway was completed and flights began the next night after the landing.38

Photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

Early Success

In the morning a dozen light planes from the Air Commando flew a risky flight in daylight at tree top level to land and bring out the serious wounded. With the landing strip prepared by the evening, that night C-47s began landing. The first night of operations saw nearly 50 C-47s landing with men, mules, & equipment. The senior RAF ground officer Robert Thompson signaled back, "La Guardia has nothing on us. Can take over 100 a night."4 Over the next week during with moon conditions at three-quarters to full, C-47 transports and light planes made regular landings without any accidents. On March 6th nine gliders landed at Chowringhee with men to clear a landing strip there. A few nights later and with the aid of a bulldozer flown in a rough landing strip was ready. Hundreds of transport flights came in bringing in the rest of the 77th and 111th brigades to both landing strips.

"Nobody as seen a Transport operation until he has stood at Broadway under the light of a Burma full moon and watched Dakotas coming in and taking off in opposite directions on a single strip all night long at the rate of one landing or one take-off every three minutes," commented one RAF general on the

volume and efficiency

of control.5 Within a week after 579 transport sorties, Wingate had 9,052 men, 10 artillery pieces, 1,359 animals & 254 tons of supplies inside Burma.7

In the morning a dozen light planes from the Air Commando flew a risky flight in daylight at tree top level to land and bring out the serious wounded. With the landing strip prepared by the evening, that night C-47s began landing. The first night of operations saw nearly 50 C-47s landing with men, mules, & equipment. The senior RAF ground officer Robert Thompson signaled back, "La Guardia has nothing on us. Can take over 100 a night."4 Over the next week during with moon conditions at three-quarters to full, C-47 transports and light planes made regular landings without any accidents. On March 6th nine gliders landed at Chowringhee with men to clear a landing strip there. A few nights later and with the aid of a bulldozer flown in a rough landing strip was ready. Hundreds of transport flights came in bringing in the rest of the 77th and 111th brigades to both landing strips.

"Nobody as seen a Transport operation until he has stood at Broadway under the light of a Burma full moon and watched Dakotas coming in and taking off in opposite directions on a single strip all night long at the rate of one landing or one take-off every three minutes," commented one RAF general on the

volume and efficiency

of control.5 Within a week after 579 transport sorties, Wingate had 9,052 men, 10 artillery pieces, 1,359 animals & 254 tons of supplies inside Burma.7

Columns assembled and headed toward their objectives. Six columns of 77th Brigade fanned out to the southwest to establish a block chosen where the jungle-covered foothills of a mountain range reached the railway. As one column each moved into the valley to block the north & south approaches to the intended site with raids, the other four led by Calvert made for the site near a village with some hills. The march was rough going for the men and mules, the trails leading over the hills and through jungle being poor. After six days, on the 16th they reached their target area and established themselves atop a cluster of small hills astride the railway and just north of Henu. The next morning they were action, as a patrol clash led to a larger battle. A Japanese force of several hundred reinforced rear echelon troops was counter-attacking the hills from the south, using a nearby unoccupied hill as their base. Approaching the scene of the battle with reinforcements, Calvert saw the Japanese infiltrating & decided quick action was needed. He sent some of the men with him around the hill while deciding to lead the others in a charge up the hill. He shouted there was going to be a charge, "So, standing up, I shouted out Charge in the approved Victorian manner, and ran down the hill with Bobbie and the two orderlies. Half of the South Staffords joined in. Then looking back I found a lot had not. So I told them to bloody well charge, what the hell do you think you're doing. So they charged."8 Heavy hand-to-hand fighting took place on the pagoda-topped hill, the "characteristic of this fighting was its savagery."9 The hill was cleared at the cost of 23 dead while inflicting 42 on the Japanese, with the retreating Japanese forced back with more casualties.10 The Chindits set to work to establish the block & with the aid of supply drops soon it was turned into a fortified defensive base 1000 by 800 yards.11 It picked up the name White City due to the number of parachutes adorning the drop zone trees.

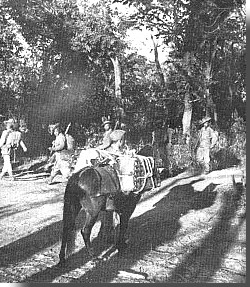

photo caption

Chindits of a Gurkha battalion at Broadway moving out with their mules. The attached Burmese company set up an intelligence network among the Kachin civilians in the area. Medical parties were sent out to assist local Kachin & Burmese civilians as part of the attempt to develop this.

Photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

While most of the 77th Brigade was creating the block, two columns left behind at Broadway set about turning the landing zone into a Stronghold. Supplies were built up. Within a few days defensive lines and bunkers were constructed, wire and mines laid, medical stations set-up, and small numbers of artillery and anti-aircraft guns were flown in. While this battalion manned the defenses, another column was acting as a floater column, ready to strike the flanks of any Japanese attack against the base. Another was sent to successfully interdict the Irrawaddy to ensure no Japanese supply boats sailed north.

While most of the 77th Brigade was creating the block, two columns left behind at Broadway set about turning the landing zone into a Stronghold. Supplies were built up. Within a few days defensive lines and bunkers were constructed, wire and mines laid, medical stations set-up, and small numbers of artillery and anti-aircraft guns were flown in. While this battalion manned the defenses, another column was acting as a floater column, ready to strike the flanks of any Japanese attack against the base. Another was sent to successfully interdict the Irrawaddy to ensure no Japanese supply boats sailed north.

Two brigades now had been flown in. A stronghold and block along the railroad valley had been established by 77th Brigade. The railway line north and south of White City had already been blown up in several places. 111th Brigade was deploying toward the valley further south of White City aiming to give Calvert time to fortify his block and stronghold. While four of its columns were landing at Broadway, two with brigade headquarters under Brigadier Lentaigne were diverted to Chowringhee. Two more columns landed there and headed east for their mission towards the Chinese border. And with Fergusson's 16th Brigade columns approaching the region, soon the Chindits would have 12,000 men deep inside Japanese territory and astride their supply routes to the north. Wingate in several communications with Mountbatten hinted at the possibilities of a greater achievement. Thinking of the possibility of cutting the supply lines to the Japanese divisions facing Slim in India, he proposed if the campaign started to develop favorably the reserve brigades could be put to use further south of Indaw near Meiktila and Pakkoku, near Mandalay. He wrote, "The establishment of the three Strongholds and the introduction of 14th Brigade may be regarded as a practical certainty, unless we in turn are prepared to accept defeat."12 Meanwhile, he proclaimed a successful beginning of the operation in his rousing Order of the Day to his troops, but in a typical misuse of signal priorities in which his messages were always marked most important he also jammed the radio lines for his units.

photo caption

Wingate with some of his key commanders at Broadway. Left to right are Allison, Calvert, then Wingate's aide-de-camp Lt. Burrow, Wingate, Lt. Col. Scott (also a was a veteran of the first Chindit campaign).

Photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

The Battle Picks Up

The Japanese response was slowed by their failure to immediately recognize the location and size of the main Chindit landings. The Japanese were puzzled as to the British intentions due to the wide range of the glider mishap landings. And they were hampered by their

commander's obsession.

One of Mutaguchi's divisional commanders suggested (and again later) that the offense into India be called off due to the threat the British landings posed. Mutaguchi's was infuriated at him and dismissive of the early reports on the landing force’s size and threat. He was not about to let anything halt his cherished offense against India. He was confident that local garrisons would be able to deal with the airborne threat which he considered merely a diversion, and that as soon as his army reached India they would endanger the airfields supplying them anyway. The Japanese air force commander in Burma vehemently disagreed and felt a major airborne invasion was in progress. Pointing to the superior Allied air power and supply capability, he stated the enemy poised a direct threat to both the Japanese supply lines in northern Burma and to the continued isolation of China by land. He said this demanded a cancellation of the offense into India to allow all forces to be used against them. Mutaguchi explained he had never lost a battle yet and explicitly rejected the suggestion, "I can see that these air-borne operations are larger than estimated...but I am glad rather than sorry. The more men Wingate brings into Burma the more will be caught like rats in a trap."18

The Japanese response was slowed by their failure to immediately recognize the location and size of the main Chindit landings. The Japanese were puzzled as to the British intentions due to the wide range of the glider mishap landings. And they were hampered by their

commander's obsession.

One of Mutaguchi's divisional commanders suggested (and again later) that the offense into India be called off due to the threat the British landings posed. Mutaguchi's was infuriated at him and dismissive of the early reports on the landing force’s size and threat. He was not about to let anything halt his cherished offense against India. He was confident that local garrisons would be able to deal with the airborne threat which he considered merely a diversion, and that as soon as his army reached India they would endanger the airfields supplying them anyway. The Japanese air force commander in Burma vehemently disagreed and felt a major airborne invasion was in progress. Pointing to the superior Allied air power and supply capability, he stated the enemy poised a direct threat to both the Japanese supply lines in northern Burma and to the continued isolation of China by land. He said this demanded a cancellation of the offense into India to allow all forces to be used against them. Mutaguchi explained he had never lost a battle yet and explicitly rejected the suggestion, "I can see that these air-borne operations are larger than estimated...but I am glad rather than sorry. The more men Wingate brings into Burma the more will be caught like rats in a trap."18

There were no contingency plans to oppose an airborne invasion. As a result, only local garrison and rear area troops were left to deal with the Chindits initially. Mutaguchi's more cautious superior in Rangoon, General Kawabe, recognized the danger to both Mutaguchi's division operating against Stilwell (18th Division) in the north, and to his main force of three divisions attacking into India. A battalion each from the 18th and 56th divisions, and two from the force marching into India were ordered into action against the Chindits. A few days later in mid-March Kawabe ordered large reserves to assemble at the town and supply depot of Indaw to deal with this threat. An infantry regiment based in southern Burma & another arriving in theater were sent north. Later sent in were several battalions of infantry & artillery ordered in from across South-East Asia. But Kawabe also refused to cancel the Indian offense.

The Japanese response would pick up as these forces gathered under the newly created 53rd Division. Totaling ten battalions of infantry plus artillery, these were regiments, battalions and artillery batteries that were desperately needed as reinforcements at Imphal and Kohima. As Mutaguchi put it, "It was a matter of great regret and concern to me that Burma Area Army switched one entire division to cope with the enemy airborne forces, especially at a time when the provision of one regiment of the 53rd Division for the Imphal front might well have ensured success of that operation."19 With communications to the 18th Division fighting in northern Burma against Stilwell’s Chinese gravely threatened, with the growing danger from an attack across the Salween, being responsible for the main offense against Imphal, and now having to face the Chindits, Mutaguchi was finding his attentions divided & unfocused. He did not move his headquarters to west of the Chindwin until late April. Thus he lacked the battlefield touch of understanding the state of the fighting in India and, "liaison with the divisions involved in the Imphal operation was inadequate and resulted in alienating the divisional commanders from Army headquarters."20

photo caption

US light plane takes off from airstrip at White City. They allowed the columns to retain mobility by evacuating out wounded & sick. Making their world combat debut was the helicopter, several of which were available rescuing downed pilots and sick troops.

US Air Force Photo

White City's location blocking Japanese communications northward to their 18th Division meant Calvert's 77th Brigade there would become the main target. His men had spent the last few days after establishing the block by digging in on the collection of small hills and the valleys in between. Fields of fire for the heavy weapons were set up and coordinated, radio lines connected the strong points to one another. Barbed wire and mines to cover the camouflaged trenches and dugouts were erected on all flanks. Open paddy fields lay to the west, the eastern flank covered by dense forest. To the south lay the village of Mawlu with some forest amid more paddy fields, while to the north several small, covered hills crept close to the perimeter. Well supplied with airdrops every night, an airstrip for the lights planes was scratched out between the railway embankment and the hills. The defenses were in the hands of four columns, while two more roamed 10-20 miles each to the north and south to harass enemy movements.

White City's location blocking Japanese communications northward to their 18th Division meant Calvert's 77th Brigade there would become the main target. His men had spent the last few days after establishing the block by digging in on the collection of small hills and the valleys in between. Fields of fire for the heavy weapons were set up and coordinated, radio lines connected the strong points to one another. Barbed wire and mines to cover the camouflaged trenches and dugouts were erected on all flanks. Open paddy fields lay to the west, the eastern flank covered by dense forest. To the south lay the village of Mawlu with some forest amid more paddy fields, while to the north several small, covered hills crept close to the perimeter. Well supplied with airdrops every night, an airstrip for the lights planes was scratched out between the railway embankment and the hills. The defenses were in the hands of four columns, while two more roamed 10-20 miles each to the north and south to harass enemy movements.

The first attack was put in by the Japanese rear area troops reinforced by several reserve companies hastily assembled from the 18th Division. This was easily driven off with the Japanese attackers not even making it past the wire. The Japanese then brought up several infantry battalions, and a loose siege began. Probing raids began March 19th to the north and south. Continuing over the next several nights, these started forcing the Chindits at White City to fight small, pitched battles. On the night of March 21 they launched their main assault on the northern defenses. Several times during the dark they rushed in, meeting wire and concentrated defensive fire from machine guns & mortars. Taking heavy casualties, they penetrated the perimeter and some close-quarter fighting took place. At dawn a series of counter-attacks supported by flamethrowers and the low-flying Air Commandos were launched, and the attackers were thrown back to the wire again. No.1 Air Commando was effective in its ground support role, with its quick response time and accuracy of its bombing and cannon fire. RAF men on the ground with voice contact would inform the pilots where the target was, and the attacking aircraft would come in parallel to friendly ground forces. Smoke would be used for marking by troops, and the bombings could be so precise as to be within several dozen yards of Chindit troops. By controlling air strikes from the ground last minute adjustments could be made. A column moved to operate outside the block to strike against the Japanese flank, driving them away from the perimeter. Air strikes were put in against the Japanese survivors on the hills. Repulsed with heavy losses, the Japanese suffered more losses from the air strikes as they retreated. At a cost of over 70 Chindit casualties, Calvert had held.21

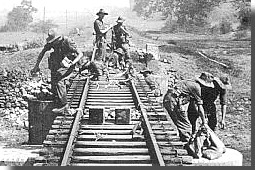

photo caption

Chindits from a column of 77th Brigade preparing a section of the railway for demolition. From White City Calvert dispatched patrols both to the north & south to destroy the railroad line and bridges.

Photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

Not content to remain merely static by simply blocking Japanese lines of communications, Calvert’s units sallied forth to attack and dominate the enemy. Patrols and raids were sent out to attack nearby Japanese garrisons and the gathering reinforcements before they could be consolidated for more attacks against the block. To the north a column attacked and pushed the Japanese several dozen miles away from White City. A pair of columns moved to attack a few miles to the south against strong Japanese defenses in Mawlu. With the aid of an air strike they fought their way in and drove several hundred Japanese out of the village, from where they retreated several dozen miles away to Indaw. A third column sent around the flank of Mawlu to cut-off their retreat fought a Japanese patrol during the night, and being delayed was unable to get into position quick enough to prevent their escape. Raids were regularly sent out destroying the railroad line up and down with explosives and mines. Patrols engaged in ambushing and mining truck and mule convoys attempting to by-pass the railway and use the few roads and jungle tracks running in the valley. The rail and roads in the valley remained blocked.

Not content to remain merely static by simply blocking Japanese lines of communications, Calvert’s units sallied forth to attack and dominate the enemy. Patrols and raids were sent out to attack nearby Japanese garrisons and the gathering reinforcements before they could be consolidated for more attacks against the block. To the north a column attacked and pushed the Japanese several dozen miles away from White City. A pair of columns moved to attack a few miles to the south against strong Japanese defenses in Mawlu. With the aid of an air strike they fought their way in and drove several hundred Japanese out of the village, from where they retreated several dozen miles away to Indaw. A third column sent around the flank of Mawlu to cut-off their retreat fought a Japanese patrol during the night, and being delayed was unable to get into position quick enough to prevent their escape. Raids were regularly sent out destroying the railroad line up and down with explosives and mines. Patrols engaged in ambushing and mining truck and mule convoys attempting to by-pass the railway and use the few roads and jungle tracks running in the valley. The rail and roads in the valley remained blocked.

At Broadway Japanese also threw in an attack. An RAF fighter aircraft squadron daringly flew into Broadway and set up their base on the 12th. The first assault came the next day by air, the Japanese throwing in most of their serviceable aircraft in Burma into bombing the stronghold. Surprised by the appearance of the British fighter planes, they lost several aircraft. While bulldozers could fill bomb craters, eventually over the course of several raids the fighter squadron was whittled down and the survivors were withdrawn. While this was occurring, information was coming in from patrols of the Burmese infantry unit and the local Kachin people of the movements of a Japanese forces advancing on Broadway. With the small artillery and anti-aircraft units flown in prepared, the commander of the force at Broadway awaited with his men.

The ground attack went in on the night of March 27th. Undertaken by a battalion from the 56th division facing the Salween River front, they were supported by several light artillery pieces. The night attack began as the force suddenly struck a company in position along the northern edge of the clearing. Furious hand-to-hand fighting took place and the defenders were overun, the survivors seeking shelter in the jungle. Seeking a way into the main perimeter in the trees on the east side of the clearing, they crossed the airstrip and launched assaults from several directions against the Gurkha defenders. They were beaten back and unable to penetrate the main defenses, the fighting continuing until daylight. The next day one Gurkha company moved outside the perimeter to put in a charge against the Japanese flank. While killing scores of Japanese in close-quarter fighting, they were forced to withdraw due to heavy sniping from the trees. The artillery unit emplaced on Broadway was able to destroy the Japanese artillery section. The floater column arrived to put in an attack but striking with only part of its force was unsuccessful. Two days later the column launched a more determined & reinforced attack with air strikes, forcing the Japanese to withdraw from their positions. With over 200 casualties (British losses about half), they retreated away from Broadway.23 Kachin guerillas picked off the stragglers from the depleted force.

photo caption

U.S. fighter-bombers low over Indian airfield. The Allies enjoyed air superiority, making the mission possible. They outnumbered the enemy in the air by 6-1.39 The Air Commando carried out several raids during the first week whittling down Japanese air strength even more.

U.S. Air Force photo

Difficulties Mount

Further east, two columns that had landed at Chowringhee were in action. They were to operate from ridges & forests overlooking the road and bridges on the Bhamo-Myitkiyina route. This was the secondary supply lines of the 18th Division, and part of that for the Japanese force on the Salween. Called Morris Force after their commander Colonel Morris, one column led by an aggressive commander was successfully waging a classic guerilla war against Japanese troops & transports. They raided positions along the road & blew bridges, setting roadblocks and ambushing traffic. Regular movement on the road was blocked and they were diverting Japanese units. The other column was hampered by Morris who took to personally running it. Not psychologically capable of leading a force behind enemy lines in the Chindit role he was a man, "who might have been eminently suitable to command a conventional Indian Army brigade. But he was overbearing, tactless and authoritarian, the last man to be entrusted with the political and military subtleties of clandestine warfare."24 Fearful of detection and dreading to stay in one place for too long, he created much frustration with his constant changing of supply drops. Excessively cautious in striking, favorable opportunities were passed up causing dissention among his officers. Success also could not be fully exploited due to the distance from airbases hindering timely air support & supplies. In the distant, rugged area radio communications were also poor. A small detachment was alongside to stir up the local Kachins in rebellion. While providing some food, villagers were fearful of Japanese retribution without the Allies staying to protect them. The small force with inadequate cadre did not enjoy success.

Further east, two columns that had landed at Chowringhee were in action. They were to operate from ridges & forests overlooking the road and bridges on the Bhamo-Myitkiyina route. This was the secondary supply lines of the 18th Division, and part of that for the Japanese force on the Salween. Called Morris Force after their commander Colonel Morris, one column led by an aggressive commander was successfully waging a classic guerilla war against Japanese troops & transports. They raided positions along the road & blew bridges, setting roadblocks and ambushing traffic. Regular movement on the road was blocked and they were diverting Japanese units. The other column was hampered by Morris who took to personally running it. Not psychologically capable of leading a force behind enemy lines in the Chindit role he was a man, "who might have been eminently suitable to command a conventional Indian Army brigade. But he was overbearing, tactless and authoritarian, the last man to be entrusted with the political and military subtleties of clandestine warfare."24 Fearful of detection and dreading to stay in one place for too long, he created much frustration with his constant changing of supply drops. Excessively cautious in striking, favorable opportunities were passed up causing dissention among his officers. Success also could not be fully exploited due to the distance from airbases hindering timely air support & supplies. In the distant, rugged area radio communications were also poor. A small detachment was alongside to stir up the local Kachins in rebellion. While providing some food, villagers were fearful of Japanese retribution without the Allies staying to protect them. The small force with inadequate cadre did not enjoy success.

111th Brigade columns were heading for the area south of Indaw, the operating area to prevent enemy reinforcements traveling north against White City. With the Broadway landings proceeding smoothly, due to the fear of the Japanese air force discovering Chowringhee no more troops were inserted at there (The Japanese air force did discover and bomb the landing zone just hours after it was vacated on the 10th). Heading west for a rendezvous with his Broadway-landed columns, the two columns with Lentaigne had to cross the Irrawaddy. Gliders arrived on the riverbank bringing heavy boating equipment. With a single fighter piloted by Allison overhead providing cover, the force attempted to cross. As the day wore on, due to poor training & obstinate mules that refused to swim only half the men made it across. Not wanting to linger anymore during daylight, a nervous Lentaigne diverted the remaining column that had yet to cross to join Morris Force further east. He took the other column on & into their first action March 20th. But they were hindered by the cautious & nervous leadership of Lentaigne, who was not holding up well under the strain of command. Fearful of taking on the Japanese and hesitating to collect supply drops, little was accomplished other than lots of exhaustive marching. His senior staff officer had to persuade him not to send a signal to Wingate that inflated an accidental clash with villagers into one with strong Japanese patrols. The Broadway columns had to march a longer distance to reach the area, and one was ambushed & delayed on the way. Consequently the brigade was unable to establish itself in strength until month’s end to begin interdicting communications. They were too late to delay the Japanese concentrating reinforcements at Indaw. Three reinforced infantry battalions reached Indaw before 111th Brigade could began striking railway & roads.

photo caption

Chindit column on the march. For nearly two months Fergusson's force had been moving and living among forests with trees overhead. Reaching the pleasant, open valley that would be stronghold Aberdeen he wrote, "I found myself gasping at its beauty."40

Photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

Fergusson's 16th Brigade was also behind schedule. To reach the Chindwin through the often unmapped & poorly surveyed terrain had been more difficult than originally planned. There was another 150 miles of hard marching yet to go. Only six columns continued on, two others being detailed to assist Stilwell’s flank. Moving single file, they slashed their way agonizingly forward in the monotony of long marching in which, "an ordinary soldier saw the same thing in front of him day after day in absolute slavery."25 The original plan called for Fergusson to be in the Meza River area west of the railway valley by March 15th. They arrived only on March 20th. There, 25 miles northwest of Indaw or a two-day march (and 20 miles west of White City), they established stronghold Aberdeen. Wingate flew in to meet Fergusson that day. He had changed the mission a week before for Fergusson's brigade from harassing the enemy to actually

capturing and holding

Indaw and its main airfield. Indaw was important not just as the supply base to the 18th Division operating against Stilwell but as a depot for the northern division fighting in India. Wingate was hoping to fly in his reserve Chindit brigades, perhaps even a complete infantry division from Slim, with the ambition to interdict the southern-most Japanese supply lines running west to their units locked in fighting in India. The 3,000 men of Fergusson's columns had spent a grueling 6 weeks marching 450 miles with their pack animals and equipment. They were tired physically & mentally, and the area he had to march across to reach Indaw contained no water. Fergusson wished first to rest & organize them, and conduct reconnaissance of the enemy positions. But hoping to achieve surprise before strong enemy reinforcements arrived, Wingate ordered Fergusson to launch an attack right away with all speed. The brigade set off on March 24th.

Fergusson's 16th Brigade was also behind schedule. To reach the Chindwin through the often unmapped & poorly surveyed terrain had been more difficult than originally planned. There was another 150 miles of hard marching yet to go. Only six columns continued on, two others being detailed to assist Stilwell’s flank. Moving single file, they slashed their way agonizingly forward in the monotony of long marching in which, "an ordinary soldier saw the same thing in front of him day after day in absolute slavery."25 The original plan called for Fergusson to be in the Meza River area west of the railway valley by March 15th. They arrived only on March 20th. There, 25 miles northwest of Indaw or a two-day march (and 20 miles west of White City), they established stronghold Aberdeen. Wingate flew in to meet Fergusson that day. He had changed the mission a week before for Fergusson's brigade from harassing the enemy to actually

capturing and holding

Indaw and its main airfield. Indaw was important not just as the supply base to the 18th Division operating against Stilwell but as a depot for the northern division fighting in India. Wingate was hoping to fly in his reserve Chindit brigades, perhaps even a complete infantry division from Slim, with the ambition to interdict the southern-most Japanese supply lines running west to their units locked in fighting in India. The 3,000 men of Fergusson's columns had spent a grueling 6 weeks marching 450 miles with their pack animals and equipment. They were tired physically & mentally, and the area he had to march across to reach Indaw contained no water. Fergusson wished first to rest & organize them, and conduct reconnaissance of the enemy positions. But hoping to achieve surprise before strong enemy reinforcements arrived, Wingate ordered Fergusson to launch an attack right away with all speed. The brigade set off on March 24th.

photo caption

General Wingate aboard a C-47 for a flight into Burma. At Aberdeen he picked out the airfield for the stronghold. It was not particularly liked by pilots as one one end there was a hill. One pilot, used to landing blind during darkness aided by a flare path, said when he saw the strip by day the first time he nearly had a fit.

Photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

Setbacks

The force would approach from the north. Between their objective of the town & airfield which lay together was a lake on the north side of Indaw. A long forested ridge lay to its northeast. Fergusson sent his columns in divided, "as clutching fingers from all sides, and not as a fist."27 Knowing his men & animals would need water after crossing the parched landscape, two columns would first advance to the north side of the lake before moving down to attack from the northeast. Two columns would use the ridge northeast of Indaw to attack from the east. One column would sweep down west of the lake to attack Indaw from the west. The last column would block the road westward out of Indaw, the northern-most supply route to India. Expecting a thousand defenders, Fergusson didn't realize there were three reinforced infantry battalions near Indaw.

The force would approach from the north. Between their objective of the town & airfield which lay together was a lake on the north side of Indaw. A long forested ridge lay to its northeast. Fergusson sent his columns in divided, "as clutching fingers from all sides, and not as a fist."27 Knowing his men & animals would need water after crossing the parched landscape, two columns would first advance to the north side of the lake before moving down to attack from the northeast. Two columns would use the ridge northeast of Indaw to attack from the east. One column would sweep down west of the lake to attack Indaw from the west. The last column would block the road westward out of Indaw, the northern-most supply route to India. Expecting a thousand defenders, Fergusson didn't realize there were three reinforced infantry battalions near Indaw.

As the tired lead column advanced on March 26th, it bumped into a Japanese outpost to the north of the lake. This alerted the enemy already prepared for them, due to a column of the 111th Brigade which passing days earlier had spread false rumors to the locals that an attack against Indaw was coming. This was part of their own deception as they headed south of Indaw, and they were not informed of 16th Brigade’s plan. Realizing their enemy would need water, the Japanese deployed accordingly. The two columns approaching the north side of the lake ran into Japanese defenses in a village along its shore and were surprised. A desperate round of fighting ensued over two days. One of the columns was able to hold off the initial Japanese attacks. Then enemy fire killed many of its mules, setting-off an inferno of exploding ammunition & flamethrower fuel. The unit slowly fell back under fire and after a desperate search found water. Its sister column was also halted by the Japanese, and the commander's decision to disperse and reform contributed to its disintegration. It was split up & suffered heavy casualties. The commander did round up some of his men & proceeded towards the other force further east. The rest were forced westward in the desperate attempt to find water. Upon reaching a stream some of the men & mules bolted across the open field in order to quench their unbearable thirst, presenting easy targets for the waiting Japanese. The column supposed to sweep in from the west had encamped the night before inadvertently along an unmarked road. A Japanese convoy drove through and in the confused fighting the column was dispersed. Further west, the column along the road leading west out of Indaw proceeded to block it. They made several successful ambushes of supply columns, taking out dozens of vehicles & easily fending off counter-attacks.

photo caption

Chindit mortar in action. After the failed attempt on Indaw, Fergusson would write of the original plan which called for four columns to attack down the ridge together, "It was Wingate's plan and I accepted it: if I had stuck to it, we might have pulled it off."41

Photograph courtesy of

the Imperial War

Museum, London

To the east, the two columns approaching from the ridge top descended to the attack concentrating as a single battalion. Reaching the eastern edge of the airfield, they halted in the face of strong defenses & dug in along a water-filled stream. In a secure perimeter, for several days they fended off persistent Japanese counter-attacks with only light casualties. Air Commando aircraft helped them hold on providing, "the most daring and accurate close support with bomb splinters whirling into the Leicester's forward posts."28 Control and coordination of the overall attack was hampered by the fact Fergusson, who was several miles behind the lead columns,

lost radio communications

with his force. For several days he was unable to provide orders or obtain information, unable to coordinate movements & redeployments of his forces. A rumor then spread that Aberdeen was under attack and, "Those days were of unrelieved gloom."29 Finally making contact with his units, Fergusson realized the attack was failing. After three days fighting against a larger force, the Chindits near Indaw successfully broke contact and withdrew back to Aberdeen to meet up with the other columns who had retreated there.

To the east, the two columns approaching from the ridge top descended to the attack concentrating as a single battalion. Reaching the eastern edge of the airfield, they halted in the face of strong defenses & dug in along a water-filled stream. In a secure perimeter, for several days they fended off persistent Japanese counter-attacks with only light casualties. Air Commando aircraft helped them hold on providing, "the most daring and accurate close support with bomb splinters whirling into the Leicester's forward posts."28 Control and coordination of the overall attack was hampered by the fact Fergusson, who was several miles behind the lead columns,

lost radio communications

with his force. For several days he was unable to provide orders or obtain information, unable to coordinate movements & redeployments of his forces. A rumor then spread that Aberdeen was under attack and, "Those days were of unrelieved gloom."29 Finally making contact with his units, Fergusson realized the attack was failing. After three days fighting against a larger force, the Chindits near Indaw successfully broke contact and withdrew back to Aberdeen to meet up with the other columns who had retreated there.

The Developing Situation

After several meetings with his superior General Slim, Wingate obtained what he thought would aid his more ambitious plan. He heard from his chief of staff Colonel Tulloch that with the threatening situation on the Imphal-Kohima front, Slim might use two of three reserve Chindit brigades there. Wingate hurriedly met with Slim on March 21st. Wingate wanted to get his remaining units flown in, "before the rats got at it."30 He believed another Chindit stronghold should be set-up some 60 miles southwest of Indaw near the enemy supply bases of Pyingyaing and Pinlebu. It was through these two towns the two southern supply lines ran for the Japanese fighting towards Imphal. With forces operating here, they could easily interdict the supply routes and force the Japanese to withdraw from India, possibly leading to their destruction. Slim agreed to Wingate’s appreciation as it would aid his 14th Army beginning to engage the Japanese. Two of the three reserve Chindit brigades, 3rd West African & 14th Brigade, would be air-lifted into Aberdeen & White City (The other, 23rd Brigade, ended up being deployed near Kohima). On the 23rd, transports began flying in the first columns of 14th Brigade. Air supply problems were also rapidly increasing. The Japanese offense was causing the diversion of critical air transport units for reinforcements and supplies. Wingate sent a message on the 22nd to the Prime Minister asking for air reinforcements of four transport squadrons. As he was leaving his meeting with Slim, he said, "You are the only senior officer in South East Asia who doesn’t wish me dead!"32

photo caption

Wingate being seen off by Calvert at White City. He carried his own rifle with him. Wingate informed Calvert that he was awarding him a bar to his Distinguished Service Order medal, "Oh, by the way, you have a bar to your DSO. Let it go to your heart and not your head."42

U.S. Air Force photo

By March 24th General Wingate was feeling optimistic about developments. 77th Brigade under Calvert was dominating the railroad valley area from their bases at White City & Broadway, cutting off supplies to the Japanese 18th division fighting Stilwell. 111th Brigade, though late, was beginning to harass communications south of Indaw with success. 16th Brigade under Fergusson from Aberdeen was heading towards Indaw and its airfield. The first columns from 14th Brigade began arriving at Aberdeen on March 23, and were heading south. The Chindits were also cutting one of the three

supply lines

to the Japanese divisions fighting in India, and they could soon conduct operations even further south to be in position to cut the last two southern supply lines. That day Wingate flew into Broadway. Taking a light plane over to White City to assess the situation, he talked with Calvert and his troops. He showed Calvert his letter of congratulations from the Prime Minister and the President he had just received. Wingate expressed to Calvert his concern that Allied commanders would not reinforce success by bringing in more units south of Indaw to block all routes into India, but would think defensively and concentrate on the Imphal-Kohima front. By doing this he feared they would forgo the seizing of the initiative and ignore that, "There is no answer to penetration except counter-penetration,"34 When questioned by Calvert if acceding to this ambition was going beyond the immediate pre-campaign objectives, Wingate smiled and replied, "We have got to help 14th Army."35 After visiting Aberdeen he

headed back

to Imphal.

By March 24th General Wingate was feeling optimistic about developments. 77th Brigade under Calvert was dominating the railroad valley area from their bases at White City & Broadway, cutting off supplies to the Japanese 18th division fighting Stilwell. 111th Brigade, though late, was beginning to harass communications south of Indaw with success. 16th Brigade under Fergusson from Aberdeen was heading towards Indaw and its airfield. The first columns from 14th Brigade began arriving at Aberdeen on March 23, and were heading south. The Chindits were also cutting one of the three

supply lines

to the Japanese divisions fighting in India, and they could soon conduct operations even further south to be in position to cut the last two southern supply lines. That day Wingate flew into Broadway. Taking a light plane over to White City to assess the situation, he talked with Calvert and his troops. He showed Calvert his letter of congratulations from the Prime Minister and the President he had just received. Wingate expressed to Calvert his concern that Allied commanders would not reinforce success by bringing in more units south of Indaw to block all routes into India, but would think defensively and concentrate on the Imphal-Kohima front. By doing this he feared they would forgo the seizing of the initiative and ignore that, "There is no answer to penetration except counter-penetration,"34 When questioned by Calvert if acceding to this ambition was going beyond the immediate pre-campaign objectives, Wingate smiled and replied, "We have got to help 14th Army."35 After visiting Aberdeen he

headed back

to Imphal.

The future of Wingate's plan to help defeat the Japanese, and that of the Chindits, was suddenly dashed. On the night of March 24th, the twin-engine U.S. Air Commando B-25 Mitchell medium bomber carrying Major-General Wingate departed Imphal for a base further west. Along with the aircrew onboard were Wingate, his aide, and several correspondents. The aircraft flew over the series of forested ridges which lay beneath them. On the ground some forty miles west of Imphal several native tribesmen witnessed an aircraft flying in low from the east, on fire and losing altitude. It passed over their village, and after watching it disappear beyond a tree line a loud explosion sounded forth. The following day air search discovered the wreckage, and a ground party was dispatched to confirm identification. The impact & explosions had been so violent that the only items they found identifying that Wingate was on board were some of his personal letters and his pith helmet. All aboard had perished.

1. Michael Calvert, Prisoner of Hope

(London: Jonathan Cape, 1952), 28-9.

2. Christopher Sykes, Orde Wingate

(New York: World Publishing Company, 1959), 518.

3. Derek Tulloch, Wingate In War And Peace (London: History Book Club, 1972), 202.

4. Sir Robert Thompson, Make For The Hills (London: Leo Cooper, 1989), 50.

5. Thompson, 51.

6. Ibid, 51.

7. Derek Tulloch, Wingate In War And Peace (London: History Book Club, 1972), 205.

8. Calvert, 50.

9. Sykes, 521.

10. Calvert,

11. Ibid, 52.

12. Trevor Royle, Orde Wingate Irregular Soldier (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1995), 304.

13. Philip Ziegler, Mountbatten (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1985), 274-75.

14. Sykes, 522-23.

15. Ibid, 523.

16. Louis Allen, Burma, The Longest War (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1984), 154.

17. Arthur Swinson, Four Samurai (London: Hutchinson, 1968), 123.

18. Swinson, 131.

19. Calvert, 291.

20. Tulloch, 292.

21. Calvert, 58.

22. Shelford Bidwell, The Chindit War (New York: MacMillan Publishing, 1979), 124.

23. Calvert, 76-7.

24. Bidwell, 187.

25. Bernard Fergusson, The Wild Green Earth (London: Collins Publishing, 1946), 169.

26. Royle, 306.

27. Calvert, 97.

28. Bidwell, 147.

29. Fergusson, 110.

30. Bidwell, 150.

31. Tulloch, 223.

32. Royle, 308.

33. Tulloch, 292-93.

34. Calvert, 60.

35. Ibid, 61.

36. Tulloch, 229.

37. Ibid, 208.

38. Calvert, 30.

39. Allen, 339.

40. Fergusson, 82.

41. Ibid, 102.

42. Calvert, 62.