C a n n o n s A n d C a m el s

T h e A d v a n c e

T h e A d v a n c e

T h e A d v a n c e

The Advance Forward

photo caption

Mount Belaiya, Gideon Force's initial destin-

ation. Because of its location amid inhospit-

able terrain the Italians had never occupied it.

Photograph courtesy of

Her Majesty's Stationary

Office, U.K.

The journey eastward to Mount Belaiya was across 150 miles of sparse desert terrain, with thorn bushes, sandy riverbeds and lava-strewn ravines. There was a waterless portion of 70 miles. Gideon Force made its way in columns to avoid overcrowding at the watering holes. The Sudanese unit with its horses and camels started out first, followed by the operational centers and the Ethiopian battalion with more animals. The camel convoys with their supplies and equipment sauntered across the land, leaving their tracks by both day and night with a good moon. One British officer put it, "the camels always went their best at night, striding along with an almost ghostly read."2 The sight & smell of the corpses of dead camels, overburdened & unused to the harsh terrain, left a trail for those marching up behind to follow.

The journey across the bush and rock and took up to 2 weeks. Wingate originally tried to bring Emperor Selassie to the destination by way of trucks using compass bearing. Confident of his cross-country navigating learned in the Sudan and Palestine, one of his maxims was to never place ones trust a local guide. He ignored local advice including that from the Sudan battalion commander Boustead that his route would be too rough for vehicles. Rocky escarpments and gorges forced the party to eventually complete their travels by horse and mule. The sight of the dead camels along the way prompted the Emperor to later comment that, "they, too died for Ethiopiaís cause."4 The first groups made it to Belaiya in early February. On the 6th of February the tired party of Wingate and the Emperor arrived. In the foothills of the 9,000 foot Mount Belaiya Emperor Selassie established his headquarters, his first base inside Ethiopia. Local Patriot groups journeyed here, arriving chanting and singing of their deeds and their loyalty to the Emperor. Here, the exotic sights and sounds at the Ethiopian campfires prompted one British officer to later write that, "It was probably the strangest scene since Bonnie Prince Charlie crossed the Tweed with his Highlanders on the eve of the Industrial Revolution. Someone said: It is a cross between Peter Pan & the Forty-Five."5 On the 8th of February there came a cumbersome re-alignment in the command structure. Wingate was given military command of British and Ethiopian military forces, and Sandford was to handle all political matters and become the chief military advisor to the Emperor. Thesiger became Wingate?s liaise to the Patriot forces.

photo caption

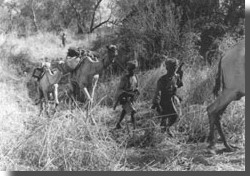

A camel convoy treading its way through the scrub of the Gojjam. Laurens van der Post, who would go on to later fame as a writer, participated & with his veterinarian concern made it to Belaiya without losing a single camel from his column.

Photo courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London

photo caption

Taken in April, the three principals of the Patriot revolt, Sandford, Selassie and Wingate. Until the command adjustment in early February, Sandford considered Wingate his subordinate.

Photo courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London

The next task was to get up an escarpment to enter into the heart of the Gojjam region. Lying some 50 miles beyond Belaiya, it was a 3,000-foot climb up to the Ethiopian highlands. A patrol rediscovered a forgotten pass up through the cliffs. After advance parties improved a crude path for the heavily-laden animals, the main body traveled up through the cliffs February 18th and the 19th.

The next task was to get up an escarpment to enter into the heart of the Gojjam region. Lying some 50 miles beyond Belaiya, it was a 3,000-foot climb up to the Ethiopian highlands. A patrol rediscovered a forgotten pass up through the cliffs. After advance parties improved a crude path for the heavily-laden animals, the main body traveled up through the cliffs February 18th and the 19th.

Initial Success

Initial skirmishing was beginning. Italian aircraft had begun raiding Mt. Belaiya, believing a large force had encamped there. Some units cooperating with Patriot forces launched raids against the Italian forts at Dangila & Engiabara, which lay just east of the edge of the escarpment, and exchanged fire with their patrols. The Italians now undertook movements which aided Wingate. In Eritrea the northern wing of the British offense was meeting with some success, and Wingate's advancing force was an unknown but threatening factor. So the Italian command decided to shorten their lines of defense & withdraw away from the escarpment. This meant abandoning posts & supplies including those at Dangila & Engiabara. Their stores provided Gideon Force with some food as local village priests gave their blessings to the arriving force.

The Italian Engiabara force withdrew 30 miles down the road to the garrison at Burye, the unit from Dangila to the northeast to a position at Lake Tana. This unit was furiously pursued by bands of Patriots for several days, which inflicted heavy casualties. Wingate dispatched a small unit of one Sudanese company and an Operational Center led by an old friend

from Palestine,

Major Simonds to the northeast. Its purpose was to raid and interdict the communications line running between major Italian bases, the road between Gondar, Debra Tabor and Dessie. Wingate was keeping his eyes fixed to the east, the heart of Gojjam. Dispatching forces to interdict in the north was only to divert attention and protect his flank, cutting-off the Gojjam to thwart any Italian attempt to counter-attack from that direction. This would also help to ensure these forces would be unable to join in the major fighting going on further north in Eritrea.

The Italian Engiabara force withdrew 30 miles down the road to the garrison at Burye, the unit from Dangila to the northeast to a position at Lake Tana. This unit was furiously pursued by bands of Patriots for several days, which inflicted heavy casualties. Wingate dispatched a small unit of one Sudanese company and an Operational Center led by an old friend

from Palestine,

Major Simonds to the northeast. Its purpose was to raid and interdict the communications line running between major Italian bases, the road between Gondar, Debra Tabor and Dessie. Wingate was keeping his eyes fixed to the east, the heart of Gojjam. Dispatching forces to interdict in the north was only to divert attention and protect his flank, cutting-off the Gojjam to thwart any Italian attempt to counter-attack from that direction. This would also help to ensure these forces would be unable to join in the major fighting going on further north in Eritrea.

photo caption

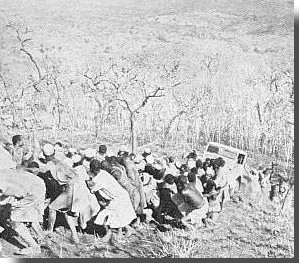

The plateau of northwest Shewa. While the men welcomed the green of the small forests, the elephant grass, and blue streams of the open plateau, the camels did not since their main food source was no longer easily available.

Photo courtesy of

Harold Marcus,

A History of Ethiopia, Regents of the U. of California, London, 1996

In front of Gideon Force lay the major fort of Burye and its outlying garrisons, on a plateau of open ground interlaced with wooded ravines and streams. Burye guarded the approaches into the heart of Gojjam. With 6,000 regular colonial infantry, the Italians were deployed in 7 colonial battalions backed by light artillery and mortars, with several thousand irregulars.8 Wingate's plan was to by-pass Burye to the north, and take up positions nearby in order to harass the garrison, its supply line, and the nearby forts. He was hoping to persuade the enemy he had strong forces and to get them to abandon Burye from bluff and bluster. Wingate would follow his own recommendation of, "One of the commonest means of obtaining surprise in war is by the use of unexpected boldness...as for example the passage of a small body of troops through the middle of an enemy position. To sum up, it may be said that surprise is the greatest weapon of the guerilla."9

Leaving their positions at Engiabara on February 24, and with a 200-mile supply route via camel, the 2-mile long column of Gideon Force

advanced south

along the only roadway. Setting off at dusk through the bush the open country the Ethiopian battalion took the lead for political reasons, the supply-carrying camels camouflaged with mud. While the first night's march proved uneventful, the second was not. Wingate led guides sent on ahead to provide a path using flashlights and torches. The Ethiopian battalion companies ran into difficulties as an enormous grass fire accidentally set upsetting their movements. The grass fire spread to a village lighting up the sky. One guide shivering in the night led some other units astray, also causing delay. Some 1,500 men with the immediate baggage train of 850 camels and horses ended up spread out over miles, all within 5 miles of Burye.11 Commented one officer on the force strung out about the countryside, "Wingate was in a great temper...He cursed Boustead...He cursed Boyle...He openly said he was sick of the 2nd Ethiopians."12 By daybreak Wingate managed to get his men together and into some woods near Burye under cover from the eyes of Italian aircraft send up to find them. The Italians nearby at Burye failed to act.

Leaving their positions at Engiabara on February 24, and with a 200-mile supply route via camel, the 2-mile long column of Gideon Force

advanced south

along the only roadway. Setting off at dusk through the bush the open country the Ethiopian battalion took the lead for political reasons, the supply-carrying camels camouflaged with mud. While the first night's march proved uneventful, the second was not. Wingate led guides sent on ahead to provide a path using flashlights and torches. The Ethiopian battalion companies ran into difficulties as an enormous grass fire accidentally set upsetting their movements. The grass fire spread to a village lighting up the sky. One guide shivering in the night led some other units astray, also causing delay. Some 1,500 men with the immediate baggage train of 850 camels and horses ended up spread out over miles, all within 5 miles of Burye.11 Commented one officer on the force strung out about the countryside, "Wingate was in a great temper...He cursed Boustead...He cursed Boyle...He openly said he was sick of the 2nd Ethiopians."12 By daybreak Wingate managed to get his men together and into some woods near Burye under cover from the eyes of Italian aircraft send up to find them. The Italians nearby at Burye failed to act.

photo caption

An Italian fort in Ethiopia. Abandoned enemy positions also aided in providing supplies.

Photo courtesy of

Harold Marcus,

A History of Ethiopia, Regents of the U. of California, London, 1996

Wanting to keep the enemy guessing and anxious, Gideon Force began raiding and ambushing the Italians. Short strikes & ambushes with local Patriot help along the road running southeast out of Burye back to Dambacha threatened Italian communications. Mortar bombardments & marksmen complemented the nightly raids by small parties of riflemen with grenades against Burye. Further east down the road mortar & machine-gun fire pounded the garrisons of the smaller forts of Mankusa and Jigga. Small units moved around the forts firing at them from all directions, trying to provoke expenditures of ammunition and morale. Wingate several times personally directed the movements and led units into action. A regular doctor joined the force soon after its arrival near Burye. Once in the moving and skirmishing around Mankusa he set up camp within machine-gun fire from the Italians inside. When asked why he was taking this risk, he replied he felt safer near the Italians than near, "that madman Wingate" whom he felt was really taking risks.13

The actions of Gideon Force and the Emperor's movement forward from Mount Belaiya were played up by the accompanying propaganda unit. Local chiefs began to see the shift in the balance of power and started to pledge support to the Emperor. Loudspeakers from the propaganda section harangued the Ethiopians inside the forts and the irregulars outside serving with the Italians, urging them to stop fighting for a lost cause and for foreigners. While most of the Italian colonial regulars held steady in the face of the situation and propaganda, the irregular forces began deserting first in small numbers, then en masse. An attempt by the Italians to neutralize the propaganda by politically handing over rule in the Gojjam to Ras Hailu did not work. He merely kept his men on the sideline, watching to see which side would seize the position of strength.

The actions of Gideon Force and the Emperor's movement forward from Mount Belaiya were played up by the accompanying propaganda unit. Local chiefs began to see the shift in the balance of power and started to pledge support to the Emperor. Loudspeakers from the propaganda section harangued the Ethiopians inside the forts and the irregulars outside serving with the Italians, urging them to stop fighting for a lost cause and for foreigners. While most of the Italian colonial regulars held steady in the face of the situation and propaganda, the irregular forces began deserting first in small numbers, then en masse. An attempt by the Italians to neutralize the propaganda by politically handing over rule in the Gojjam to Ras Hailu did not work. He merely kept his men on the sideline, watching to see which side would seize the position of strength.

The Italians failed to act decisively. The movements of Gideon Force were allowed to operate without serious interference from Italian forces. Early on, one of Bousteadís companies was raiding Burye with the mortars. Italian reply fire set fire to the grass in front of them. Then out of the smoke a cavalry charge was put in against them, but was quickly swept aside. An accompanying infantry sortie threatened a nearby camel convoy, and as was his manner Wingate intervened to take command. Dependent upon human runners due to the lack of radios (an example of lack of proper equipment support given to him), and soon having to operate in the dark, Wingate and Boustead were unable to coordinate the movements of units, causing confusion and momentary fear of losses.

After this attempt, there was a lack of aggression on the part of the Italian commanders. The movements of Gideon Force initially around Burye with the confused columns created the illusion of movements of a larger force, their raids including the actions of an Operational Center against the Burye-Dambacha road fed the notion that their activity was becoming dangerously widespread. And the continuing camel supply convoys amid concealing forests formed the impression of strong British support. Together all produced the sense that Gideon Force was stronger than it was. The Italians mistakenly credited their opponents strength at several brigades (6 battalions) accompanied by thousands of Ethiopian irregulars. The Italian commander wanted to abandon his position.

photo caption

Italian instructors with native Ethiopian allies. The high elephant grass and acacia tree forests aided in providing cover for the movements of Gideon Force from prowling Italian aircraft.

Photograph courtesy of

Her Majesty's Stationary

Office, U.K.

Action at the River

The numerically and materially superior Italian force in Burye was given permission to withdraw several dozen miles down the road to the southeast, to the fort of Dambacha. Set for March 4th, the day before Wingate received word from Khartoum, thanks to British radio intercepts & cryptanalysis, of their plans. A request for air support to strike the retiring Italians was not forthcoming (with aircraft limited these were oriented toward the heavy fighting in Eritrea). Wingate

tried to maneuver

his forces accordingly in spite of the fact he basically had no staff and no proper communications. Ordering the bulk of the Sudanese battalion to harass the retreating column after it left the safety of Burye, further on down the road on a ridge near Mankusa he positioned himself with one company. The Ethiopian battalion had earlier been sent ahead some 25 miles further down the road near Dambacha at the Charaka River, and encamped under cover was preparing to raid the fort and nearby road. As the only radio set was with him, Wingate sent word of the Italian retreat via the traditional method of communication, a runner, to the battalion. The message never arrived.

The numerically and materially superior Italian force in Burye was given permission to withdraw several dozen miles down the road to the southeast, to the fort of Dambacha. Set for March 4th, the day before Wingate received word from Khartoum, thanks to British radio intercepts & cryptanalysis, of their plans. A request for air support to strike the retiring Italians was not forthcoming (with aircraft limited these were oriented toward the heavy fighting in Eritrea). Wingate

tried to maneuver

his forces accordingly in spite of the fact he basically had no staff and no proper communications. Ordering the bulk of the Sudanese battalion to harass the retreating column after it left the safety of Burye, further on down the road on a ridge near Mankusa he positioned himself with one company. The Ethiopian battalion had earlier been sent ahead some 25 miles further down the road near Dambacha at the Charaka River, and encamped under cover was preparing to raid the fort and nearby road. As the only radio set was with him, Wingate sent word of the Italian retreat via the traditional method of communication, a runner, to the battalion. The message never arrived.

photo caption

Struggling to get a supply truck up the escarpment. Behind the advance an engineering group spent their time cutting trees and leveling out the ground for a rudimentary road. Supplementing their efforts were occasional air transport flights.

Photograph courtesy ofHer Majesty's StationaryOffice, U.K.

After dawn on the 4th, the retreating Italian force began its retreat with some 6,000 troops preceded by several armored cars and a bomber overhead, "With truck-loads of infantry and a few armored cars, cavalry and artillery and swarms of bande fleeing the Emperorís wrath."14 Rather than strike the column with gunfire however, Colonel Boustead did not do so, feeling his smaller force was at a tactical disadvantage. As part of the Italian covering action, the small force with Wingate was attacked by the withdrawing garrison at Mankusa. Initially standing and fighting, he was soon forced to hurriedly withdraw. When Wingate found out about the inaction by the Boustead he flew into a rage at Boustead, accusing him of cowardice. Wingate quickly ordered a pursuit of the Italians, while other forces invested Burye with its large supplies of food and gasoline. That evening and into the next day, small harassing attacks were put in against the retreating Italian column but without serious disruption as Italian counter-attacks forced the parties to withdraw.

Two days later retreating Italian column ran into the Ethiopian force astride the road near Dambacha. The battalionís commander, Major Boyle, had failed to send out patrols when he heard rumors from Patriots about the Italians retreating from Burye. Instead, he had already begun to send out one company in preparation for a raid against Dambacha. The advance guard of the Italian force rushed ahead to punch through the Ethiopian front and cross the Charaka river. Though surprised, the Ethiopian battalion quickly deployed. Putting up fierce resistance, the initial Italian assault was repulsed. With their rearguard patrols holding off Boustead pressing down from the northwest, the main Italian element began to deploy. After hours of heavy fighting, the Italians began fighting through their opponents. Outnumbered and with ammunition running short, the Ethiopians were forced aside. They had been unable to prevent the main Italian force from escaping across the Charaka and suffered some 48 casualties, but had inflicted over 344 on the Italian force.17 In their haste to retreat the Italians failed to destroy the bridge over the river behind them. Furthermore, against orders the Italian commander abandoned Dambacha and Gideon Force occupied it March 8th.

Two days later retreating Italian column ran into the Ethiopian force astride the road near Dambacha. The battalionís commander, Major Boyle, had failed to send out patrols when he heard rumors from Patriots about the Italians retreating from Burye. Instead, he had already begun to send out one company in preparation for a raid against Dambacha. The advance guard of the Italian force rushed ahead to punch through the Ethiopian front and cross the Charaka river. Though surprised, the Ethiopian battalion quickly deployed. Putting up fierce resistance, the initial Italian assault was repulsed. With their rearguard patrols holding off Boustead pressing down from the northwest, the main Italian element began to deploy. After hours of heavy fighting, the Italians began fighting through their opponents. Outnumbered and with ammunition running short, the Ethiopians were forced aside. They had been unable to prevent the main Italian force from escaping across the Charaka and suffered some 48 casualties, but had inflicted over 344 on the Italian force.17 In their haste to retreat the Italians failed to destroy the bridge over the river behind them. Furthermore, against orders the Italian commander abandoned Dambacha and Gideon Force occupied it March 8th.

1. W. E. D. Allen, Guerilla War in Abyssinia

(London: Penguin Books, 1943), 38.

2. David Shirreff, Bare Feet And Bandoliers (London: Radcliffe Press, 1995), 71.

3. Wilfred Thesiger, The Life of My Choice (London: Collins, 1987), 334.

4. Emperor Haile Selassie (Edited by Edward Ullendorff), My Life And Ethiopia's Progress, Vol.II (East Lansing: Michigan State U Press, 1994), 144.

5. Allen, 65.

6. Shirreff, 78.

7. Ibid, 88.

8. Ibid, 91-2.

9. Trevor Royle, Orde Wingate Irregular Soldier (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1995), 191.

10. Royle, 192.

11. Christopher Sykes, Orde Wingate (New York: World Publishing Company, 1959), 273.

12. Shirreff, 93.

13. Ibid, 96

14. Allen, 74.

15. Thesiger, 350.

16. Shirreff, 221.

17. Ibid, 119.