T h e G r e a t V i c t o r y

T h e V i c t o r y

T h e V i c t o r y

T h e V i c t o r y

Debra Markos

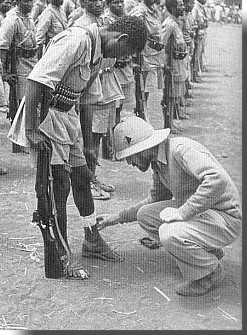

photo caption

Wingate at Dambacha inspecting troops of the 2nd Ethiopian battalion. While here Wingate tried to recover from an infected foot and an attack of malaria, which would plaque him for the rest of his life. Wingate's spirits were bolstered by the arrival of Jewish doctors from Palestine he had sent for.

Photo courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London

The fort of Debra Markos was the next target on the way to Addis Ababa. The last major fortification on the road before the Blue Nile River, Wingateís plan was to bypass it and force the enemy out. He was confident his 1,500-man force supported by Patriots & Operational Centers could accomplish this by using hit-and-run raids and cutting the supply lines on the road back to Addis Ababa. While his men briefly rested, the administrative side tried to catch up. The crude vehicle route from the Sudan was completed (a dozen trucks were man-handled up the escarpment) to Burye, along with an airstrip for the movement of some supplies and casualty evacuation.

Part of the tactic of repeating his success as at Burye meant leading from the front. With the poor communications and a quickly changing situation, this style by Wingate often led to others being unaware of his location or original intention. During the fighting he clashed with Sandford over the running of operations. Sandford believed the overall mission should still be a holding one. Once, back near Burye he was ordered by General Platt to do his best to help tie down the Italians in the region. With messages slow in reaching Wingate, he decided to divert some supplies and a pair of operational groups to Patriots operating with Simonds to the north. He also wrote Wingate criticizing his silence. Wingate angrily returned to Burye to resolve matters with Sandford. As one noted, "Orde suddenly appeared without warning and was out looking for blood. However, his magnetic personality dominated and dispelled all disgruntled thoughts, although he was very critical of the things that [had] been sent forward from here."1 Meeting with Sandford, Wingate lashed out at him for not concentrating on the more important front where he was, and of distributing arms to Patriots regardless of their military prowess. In turn Wingate was criticized for having a weak administration & for not being around headquarters leaving him, Sandford, to make important decisions. Platt intervened and ordered all squabbling to cease, to leave military matters to Wingate and administrative matters to Sandford, and to focus upon fighting the Italians.

The clash with Sandford over distributing weapons and ammunition to the rebels came from Wingate's approach to guerilla warfare and partial distrust of the Patriots military usefulness. On February 7th while still at Mount Belaiya, Wingate had ordered a halt to arms distribution to Patriots except for those coming under operational control of the Operational Centers.4 This was due to the experiences such as one group of Patriots refusing to fight unless more weapons and ammunition were provided, and then selling them to the Italians. And of the fact that some Patriots in the liberated areas seemed more interested in looting than fighting. After the action at the Charaka River, Gideon Force was forced to take action against local Patriots looting the Ethiopian battalionís camp. While Gideon Force enjoyed good cooperation from local Patriot forces, in some regions there was apathy toward continuing the fighting with other military forces arriving. As Thesiger put it, "They had been fighting the Italians for four years. Now that the regulars had arrived, their view was, 'Let them get on with it. Why should we get killed at the last minute?"6

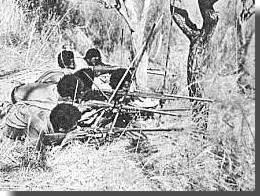

photo caption

Ethiopian Patriot guerillas during a pause in the campaign. With air support limited, several rare air raids were put in against the Italians at Debra Markos.

Photo courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London

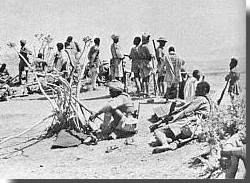

photo caption

Patriots outside Debra Markos. While the largest action around Debra Markos involved several companies from the Ethiopian battalion in raid that lasted several hours, most fighting was at platoon and squad patrol level.

Photo courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London

In mid-March the confident force advanced forward to face a new Italian commander, Colonel Maraventano. He was appointed command of the Italian force of nearly 9,000 regular and colonial infantry, supported by 5,000 Ethiopian irregulars led by Ras Hailu.7 The Italians were planning on making Debra Markos part of a new fortified zone being created for a stand in Ethiopia in the hopes of holding out as along as possible and to tie down as many Allied troops as possible. Maraventano positioned his main force on a series of fortified hilltops around Gulit ridge, which lay some 12 miles northwest of Debra Markos. They were backed by several small forts of stone walls, entrenchments and barbed wire that lay around Debra Markos. Around the Italians to the western and north were large hills while to the east an open plateau with the road stretched back 50 miles southeast to the ravine of the Blue Nile River. Determined to hold out, Maraventano started proving more resilient mentally than his predecessor. During the rest of the month the two sides clashed over the hills and forts near Gulit and Debra Markos, and along the road on both sides of Debra Markos. Italian forces aggressively pushed out patrols and started to launch large counter-attacks against forward positions held by Gideon Force. They were backed up by air raids. The local population hesitated in openly choosing sides. With local Patriots hesitating in being aggressive and with the presence of Ras Hailu, Akavia wrote, "Some Chiefs who joined us are now contemplating treachery."8

In mid-March the confident force advanced forward to face a new Italian commander, Colonel Maraventano. He was appointed command of the Italian force of nearly 9,000 regular and colonial infantry, supported by 5,000 Ethiopian irregulars led by Ras Hailu.7 The Italians were planning on making Debra Markos part of a new fortified zone being created for a stand in Ethiopia in the hopes of holding out as along as possible and to tie down as many Allied troops as possible. Maraventano positioned his main force on a series of fortified hilltops around Gulit ridge, which lay some 12 miles northwest of Debra Markos. They were backed by several small forts of stone walls, entrenchments and barbed wire that lay around Debra Markos. Around the Italians to the western and north were large hills while to the east an open plateau with the road stretched back 50 miles southeast to the ravine of the Blue Nile River. Determined to hold out, Maraventano started proving more resilient mentally than his predecessor. During the rest of the month the two sides clashed over the hills and forts near Gulit and Debra Markos, and along the road on both sides of Debra Markos. Italian forces aggressively pushed out patrols and started to launch large counter-attacks against forward positions held by Gideon Force. They were backed up by air raids. The local population hesitated in openly choosing sides. With local Patriots hesitating in being aggressive and with the presence of Ras Hailu, Akavia wrote, "Some Chiefs who joined us are now contemplating treachery."8

True to their aim, Wingate's forces merely withdrew when the situation called for, choosing battle when they wished and on their terms. In this they were aided by the terrain of woods and hills, and the Italian need to hold positions. For several weeks nightly hit and run raids on Italian positions from different directions became the standard action. Strikes to machine gun and grenade the Italian fortified positions around Gulit ridge were undertaken. One tactic was to move up to the enemy forward positions as close as possible during the night, then launch grenades and charge the Italian line with bayonet, then withdraw quickly. Deserters sometimes provided them with the locations of Italian forces and their expected counter-attacks. Close reconaissance preceeded mortar bombardments against the forts. Wingate was one of few officers with mortar handling experience and he had no hesitation in showing leadership by taking part in the close-in fighting. Once, manning a small mortar Wingate ordered his Ethiopian assistant to safety as Italian shells began dropping close by. Explaining afterwards his determination to remain behind, he declared, "If you were killed you would be a great loss to your country because in Ethiopia there is a shortage of well-educated men, but if I am killed it is another matter. There are plenty of people in England to take my place."9

The road from Gulit back to Debra Markos were mined. Also targeted for ambush were the supply convoys heading for Debra Markos from across the Nile, while Italian patrols coming out from Debra Markos were fired upon. Such actions began forcing the Italians to divide their forces between the forward positions and along their communication line back to Debra Markos. The Italians were losing men nightly in hit and run attacks and ambushes, slowly being drained of manpower and willpower. In a period of a couple of weeks they lost close to 200 men while Gideon Force lost only 34.10 The aggressive actions by the two battalions, some Patriots and the handful of active operational centers were convincing the Italians they were facing a large enemy presence.

The road from Gulit back to Debra Markos were mined. Also targeted for ambush were the supply convoys heading for Debra Markos from across the Nile, while Italian patrols coming out from Debra Markos were fired upon. Such actions began forcing the Italians to divide their forces between the forward positions and along their communication line back to Debra Markos. The Italians were losing men nightly in hit and run attacks and ambushes, slowly being drained of manpower and willpower. In a period of a couple of weeks they lost close to 200 men while Gideon Force lost only 34.10 The aggressive actions by the two battalions, some Patriots and the handful of active operational centers were convincing the Italians they were facing a large enemy presence.

photo caption

A pontoon bridge built by engineers of a South African unit across the Juba river in southern Somalia. In the southern front troops from East and West Africa, as well as from South Africa and Britain fought.

Photo courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London

The Collapse

The regular forces & Wingate's force were assisting each other, their advances and presence dividing the enemy and preventing Italian forces from massing and counterattacking. Nation-wide, actions by the Patriots and Gideon Force were tying down over one-third (56) of the available Italian battalions, leaving only the equivalent of 71 battalions to face the main British force of 5 divisions fighting in Eritrea and from Kenya.11 British forces on the other battlefields of East Africa were meeting success. In the north, after 6 weeks of heavy fighting at the main Italian defensive position at Keren the last positions were occupied by March 27. The rest of Eritrea fell to Platt's Indian divisions in early April. In the south, resistance had collapsed. After capturing Mogadishu in Italian Somalia in late February, British forces under Cunningham raced north. By mid-March they had reached the mountain pass ways into Ethiopia and had begun the advance on Addis Ababa from the east. The deteriorating situation was reinforcing opportunities in the northwest. With a strong British force believed to be in Gojjam, the Italian command decided at the end of March that all of Gojjam needed to be evacuated.

The regular forces & Wingate's force were assisting each other, their advances and presence dividing the enemy and preventing Italian forces from massing and counterattacking. Nation-wide, actions by the Patriots and Gideon Force were tying down over one-third (56) of the available Italian battalions, leaving only the equivalent of 71 battalions to face the main British force of 5 divisions fighting in Eritrea and from Kenya.11 British forces on the other battlefields of East Africa were meeting success. In the north, after 6 weeks of heavy fighting at the main Italian defensive position at Keren the last positions were occupied by March 27. The rest of Eritrea fell to Platt's Indian divisions in early April. In the south, resistance had collapsed. After capturing Mogadishu in Italian Somalia in late February, British forces under Cunningham raced north. By mid-March they had reached the mountain pass ways into Ethiopia and had begun the advance on Addis Ababa from the east. The deteriorating situation was reinforcing opportunities in the northwest. With a strong British force believed to be in Gojjam, the Italian command decided at the end of March that all of Gojjam needed to be evacuated.

The Italian forces at Debra Markos were to be withdrawn across the Blue Nile. Then they were then to head east to Dessie to join up with other units to hold out in a mountain fastness. In stages beginning on the night of March 31, the Italians began to fall back along the road from the positions around Gulit ridge to Debra Markos. They managed to get away from Gulit without severe losses. A Sudanese company attacking the ridge meet heavy fire and were forced to withdraw. An Ethiopian company along the road hesitated about taking on the much larger force, while a message to the Sudanese unit did not reach them in time for joint action. Debra Markos was abandoned a few days later without destruction, the Italians leaving the place well-stocked with supplies. Past Debra Markos, an Operational Center and one company kept the retiring force under observation and began harassing them each step of the way. A particularly successful ambush destroyed several dozen vehicles, preventing Maraventano from bringing with him sufficient supplies. Wingate had sent Thesiger and a small force ahead with the intent to harass the roadway and make contact with a local Patriot ruler who had several thousand armed and active men. Linking up they were and attack the retreating Italian force as it lay vulnerable crossing the river ravine. But the Patriot leader failed to act and the Italian force was allowed to pass unimpeded across the Blue Nile. He had accepted a bribe from Ras Hailu (marriage to his royal daughter), the political rival of the Emperor's whom the Italians had persuaded to undertake a final act.

photo caption

Patriot forces awaiting the arrival of Emperor Selassie at Debra Markos. Boustead had a standoff with Ras Hailuís men in liberated Debra Markos. After allowing the Italians to withdraw unmolested, Ras Hailu sent his men into the Debra Markos for looting.

Photo courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London

A few days after the Italians left, on the 6th of April Emperor Selassie

entered Debra Markos.

Ras Hailu, seeing the change of power, surrendered to the Emperor's authority with his men on April 7th. Selassie began re-asserting his authority in the region as the local nobles began arriving to welcome the emperor. In a speech before the Emperor and others in mid-April, Wingate proclaimed in a toast, "Myself and the British officers under my command have born their part with the patriot Ethiopian forces in this campaign in the knowledge that, in so doing, they were supporting the same cause for which England is fighting throughout the world. The right of the individual to liberty of conscience, the right of the small nation to a just decision at the tribunal of nations, these are the causes for which we fight. Until Ethiopia was liberated the major wrong, which brought in its train the present war, had not been righted and success for our arms could not be expected."12 The way to the capital was open as Italian resistance around Addis Ababa disintegrated. The same day Emperor Selassie entered Debra Markos, British forces entered his capital.

A few days after the Italians left, on the 6th of April Emperor Selassie

entered Debra Markos.

Ras Hailu, seeing the change of power, surrendered to the Emperor's authority with his men on April 7th. Selassie began re-asserting his authority in the region as the local nobles began arriving to welcome the emperor. In a speech before the Emperor and others in mid-April, Wingate proclaimed in a toast, "Myself and the British officers under my command have born their part with the patriot Ethiopian forces in this campaign in the knowledge that, in so doing, they were supporting the same cause for which England is fighting throughout the world. The right of the individual to liberty of conscience, the right of the small nation to a just decision at the tribunal of nations, these are the causes for which we fight. Until Ethiopia was liberated the major wrong, which brought in its train the present war, had not been righted and success for our arms could not be expected."12 The way to the capital was open as Italian resistance around Addis Ababa disintegrated. The same day Emperor Selassie entered Debra Markos, British forces entered his capital.

A Final Pursuit

The regular Indian and East African units moved to clear the Italians from their last-ditch mountain refuges in the north and southwest. Gideon Force passed from General Plattís command to that of General Cunningham. While Boustead was ordered to take a small force of Sudanese north of Debra Markos and seize the fort at Mota, Wingate was to finish off the Italians retreating from the Gojjam. While a larger part of Gideon Force made for the capital, a small detachment of only a single company with an Operational Center and several hundred Patriots turned in pursuit. The retreating Italian force under Maraventano now had over 9 battalions of 7,500 troops (Italian and East African) heading northeast for Dessie.13 But the Italian garrison at Dessie found their lines of communication blocked by the operational centers & Patriots under Simonds, sent earlier by Wingate. Ambushes, mines and demonstrations were ensuring this (they would be forced to surrender to regular British forces advancing in late April). So with their route blocked, on April 11 the Italian column changed direction to the north, aiming for friendly forces in the central mountains at Amba Alagi.

They began to cut across country heading for their destination via the garrison fort at Debar Sina, 140 miles northeast of Debra Markos. As the Italian force made its way forward it was under constant threat. This side of the Nile Patriot activity was especially fierce and the Italians began suffering major desertions from the native colonial units. The column was encumbered by several thousand non-combatant civilians and a growing number of sick and wounded. On high plateaus and over rough animal tracks, across ravines and gorges, in the cold rain the equally tired & sick Allied force pursued their enemy northward. The situation was, "an enemy reduced to weakness pursued by avengers reduced to almost equal weakness by the boldness of their undertaking."14 Nightly raids and patrols by the Gideon Force detachment from their rear and the Patriots on the flanks bit away at Italian strength and endurance. Wingate arrived on May 14th with 1,200 more Patriots and took personal command.15 Morale was invigorated for what many believed was going to be a final showdown battle. Thesiger thought, "Now for the first time I really appreciated his greatness. Bearded and unkempt, he had got off his mule, stared about him with searching eyes, set face and jutting jaw, then called us together. He wasted no time. He told us that he intended to make the Italians surrender and that in a few days time."16 Receiving an order on the 15th from General Cunningham to abandon the pursuit and move to support forces operating elsewhere, Wingate replied that he could not decipher his message & closed down radio communications.

photo caption

Part of Gideon Force resting during the pursuit to Debra Sina. During the fighting here the Patriot forces suffered almost 33% casualties.23

Photo courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London

Initially at the mountain of Addis Derra the Italian rearguard managed to hold off the raids by their pursuers. But misled by the size of the force pursuing them, they abandoned the defensible position on May 16th and headed for the fort at Debar Sina just to their north. Wingate watched them depart, "Within two days of my arrival the enemy evacuated Addis Derra. Form the summit of the fort I watched his column, nearly 18 miles long, disappear into the 5,000 foot canyon and climb the far side."17 To reach Debar Sina, the Italians had to cross a high ridge on a panhandle between two plateaus to its south and north. Wingate sent Thesiger with 80 men from the Ethiopian battalion reinforced by an operational center with 300 Patriots up ahead.18 They were to maneuver around the eastern flank of the Italian force to get ahead to prevent them from getting into higher country at Debar Sina. To the enemy's rear Wingate would handle the pursuit with the Sudanese company & an influx of 2,000 fresh Patriot forces.19 On night of May 17th Thesiger's group surprised the garrison at the hilltop fort on the northern plateau which covered the ridge, the colonial irregulars there deserting. As Thesiger's men deployed along the ridge looking south towards the plateau with the enemy now atop it, Wingate prepared to advanced onto the plateau.

Initially at the mountain of Addis Derra the Italian rearguard managed to hold off the raids by their pursuers. But misled by the size of the force pursuing them, they abandoned the defensible position on May 16th and headed for the fort at Debar Sina just to their north. Wingate watched them depart, "Within two days of my arrival the enemy evacuated Addis Derra. Form the summit of the fort I watched his column, nearly 18 miles long, disappear into the 5,000 foot canyon and climb the far side."17 To reach Debar Sina, the Italians had to cross a high ridge on a panhandle between two plateaus to its south and north. Wingate sent Thesiger with 80 men from the Ethiopian battalion reinforced by an operational center with 300 Patriots up ahead.18 They were to maneuver around the eastern flank of the Italian force to get ahead to prevent them from getting into higher country at Debar Sina. To the enemy's rear Wingate would handle the pursuit with the Sudanese company & an influx of 2,000 fresh Patriot forces.19 On night of May 17th Thesiger's group surprised the garrison at the hilltop fort on the northern plateau which covered the ridge, the colonial irregulars there deserting. As Thesiger's men deployed along the ridge looking south towards the plateau with the enemy now atop it, Wingate prepared to advanced onto the plateau.

Atop this 9,000-foot plain just south of Debar Sina, the larger Italian force was caught between the two forces. Furious fighting took place on the nights of the 18th and 19th as from the south Wingateís forces heavily engaged the Italians. The Patriots, while eager had little training or weaponry in assaulting defended positions, and often were rushing forward and taking high casualties. On May 20th the Italians attempted to fight their way north through Thesigerís men on the ridge. The first two Italian attacks were driven back. But with his men becoming scattered and heavy casualties, Thesiger decided to fallback from the ridge. Retiring to the corner of the northern plateau, he was still effectively blocking the way to Debra Sina. With their rearguard under furious pressure from the south, the intensity of the resistance from both directions convinced the Italians they were facing a much larger force than they actually were. Maraventano wrote in his war diary he was launching counter-attacks, "Against forces three times our number and aggressive."20 By the end of the day, the Italian force was cornered on the plateau, sided by steep precipices and the two British forces. On the evening of May 21st, low on supplies and the number of wounded and sick increasing, Maraventano agreed to surrender terms (as did the garrison at Debra Sina). During the surrender ceremony in which the Italians were allowed to parade arms, Wingate feared the sight of his much smaller force and their lack of weaponry would cause a change in heart by the Italians. After their surrender a final ignominy awaited the Italians. On the wishes of Emperor Selassie who did not wished to be eclipsed by the success of British arms elsewhere, they were forced to parade before him.

photo caption

Wingate leading the way for the victory march into Addis Ababa. After reaching city, with no natural food at the high altitude the last surviving 53 camels were shot, to the Emperorís horror.

Photo courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London

A Final Honor

Earlier on May 5th, the main element of Gideon Force assembled with Emperor Selassie for a victory march on Addis Ababa. Cunningham had given orders to Wingate to delay bringing in the Emperor for as long as possible for security reasons. He was concerned with safeguarding European interests, to prevent fighting between the Patriots and the disarmed & retreating Italians in the area. But to Wingate and Emperor Selassie this merely

reinforced suspicions

that political machinations were afloat to bring Ethiopia under British colonial influence. The Emperor wanted to resume his role as soon as possible, to re-assert the prestige of his position and begin to reform his government. Delay meant he, "is being made to cut a very poor figure before his people, which is not only galling to him now but dangerous for him in the future."22 An angry emperor insisted on entering his capital, and having established security Cunningham agreed. On May 5th Wingate led the march on a white horse wearing his large sun helmet, ahead of a company from the Ethiopian battalion, the Emperor following in an open car. The march proceeded past Addis Ababa streets lined with soldiers & Patriots, with crowds of civilians singing & prostrating in streets. The streets were decorated with flowers & Ethiopian flags, with pictures of Emperor Selassie as St. George slaying an Italian dragon with the help of the British Army. At the royal palace Cunningham & an honor guard received the Emperor with a royal salute. It was five years to the day he had been forced to flee by the Italians. Wingate would not savor this as within a month he was no longer in Ethiopia.

Earlier on May 5th, the main element of Gideon Force assembled with Emperor Selassie for a victory march on Addis Ababa. Cunningham had given orders to Wingate to delay bringing in the Emperor for as long as possible for security reasons. He was concerned with safeguarding European interests, to prevent fighting between the Patriots and the disarmed & retreating Italians in the area. But to Wingate and Emperor Selassie this merely

reinforced suspicions

that political machinations were afloat to bring Ethiopia under British colonial influence. The Emperor wanted to resume his role as soon as possible, to re-assert the prestige of his position and begin to reform his government. Delay meant he, "is being made to cut a very poor figure before his people, which is not only galling to him now but dangerous for him in the future."22 An angry emperor insisted on entering his capital, and having established security Cunningham agreed. On May 5th Wingate led the march on a white horse wearing his large sun helmet, ahead of a company from the Ethiopian battalion, the Emperor following in an open car. The march proceeded past Addis Ababa streets lined with soldiers & Patriots, with crowds of civilians singing & prostrating in streets. The streets were decorated with flowers & Ethiopian flags, with pictures of Emperor Selassie as St. George slaying an Italian dragon with the help of the British Army. At the royal palace Cunningham & an honor guard received the Emperor with a royal salute. It was five years to the day he had been forced to flee by the Italians. Wingate would not savor this as within a month he was no longer in Ethiopia.

1. David Shirreff, Bare Feet And Bandoliers

(London: Radcliffe Press, 1995), 134.

2. Shirreff, 138.

3. W. E. D. Allen, Guerilla War in Abyssinia

(London: Penguin Books, 1943), 92-3.

4. Simon Anglim, "MI(R), G(R) and British Covert Operations, 1939-42." Intelligence and National Security Journal, Vol.20, No.4 (December, 2005), 643.

5. Shirreff, 118.

6. Ibid, 127.

7. Ibid, 88.

8. Ibid, 91-2.

9. Christopher Sykes, Orde Wingate (New York: World Publishing Company, 1959), 290.

10. Shirreff, 153-4.

11. Andrew Jackson, The Battle For North Africa (New York: Mason-Charter Publishing, 1975), 91.

12. Shirreff, 181.

13. Ibid, 160.

14. Sykes, 308.

15. Shirreff, 195.

16. Wilfred Thesiger, The Life of My Choice (London: Collins, 1987), 344.

17. Trevor Royle, Orde Wingate Irregular Soldier (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1995), 207.

18. Royle, 206.

19. Ibid, 207.

20. Shirreff, 205.

21. Ibid, 206.

22. Ibid, 176.

23. Ibid, 211.