L a s t i n g C o n t r o v e r s y

P o s t w a r D e b a t e

P o s t w a r D e b a t e

P o s t w a r D e b a t e

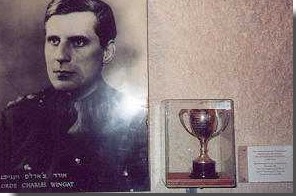

photo caption

Wingate's personal

pistol on display at the Haganah Museum in Tel Aviv, Israel.

Personal Photo

The close of WWII did not end all the battles of Orde Wingate. The last one still continuing is the clash between his supporters & his detractors over his proper place in history. Personal prejudice and defensive reaction, opponents and supporters of his ideas, selective evidence and emotional reflections, all create a maze of conflicting if not confusing source of facts and opinions to be sorted through. In Israel and Ethiopia he is considered a heroic figure, while it is in his home nation of Great Britain the most controversy exists over his accomplishments and role.

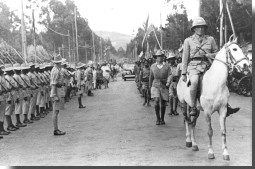

photo caption

Avraham Akavia, 2nd from the left, at the head of the parade of Gideon Force during the parade into Addis Ababa. Akavia served with Wingate & has remained a faithful defender of his memory.

Photo courtesy of the

Imperial War Museum,

London

photo caption

Wingate leading Emperor Selassie's return procession into Addis Ababa on May 5th, 1941.

photograph courtesy of

Haganah Museum, Israel

Israel

In Israel, his accomplishments are properly acknowledged. The immediate aftermath of his death amidst growing revelation of the Holocaust meant to the Jewish communit another sad day. Flags were lowered in half-mast in Palestine and tributes poured forth. The post-war image of Wingate from the writings of veterans like Moshe Dayan, Yigal Allon, Avraham Akavia, Zev Brenner, Israel Carmi, and others has remained. It is one of a pro-Zionist figure that contributed to safeguarding Israel's future in an uncertain time. Moshe Dayan remembered the "professionalism about Wingate, a positiveness, a stubborn lack of compromise. A dominating personality, he infected us all with

his fanaticism and faith."1 Preaching a determined self-reliance, as one SNS veteran put it, "He believed in Zionism as an idea, and believed in the power of the Jewish Yishuv in Eretz Israel to realize the idea and to defend itself."2 The Israeli Defense Forces, as well as historians, view him as one of its founding fathers for his ideas on offensive action and small units.

his fanaticism and faith."1 Preaching a determined self-reliance, as one SNS veteran put it, "He believed in Zionism as an idea, and believed in the power of the Jewish Yishuv in Eretz Israel to realize the idea and to defend itself."2 The Israeli Defense Forces, as well as historians, view him as one of its founding fathers for his ideas on offensive action and small units.

It is on the political fringes there have been efforts to portray Wingate in a negative light. The "New Historians" are a small group of politically-motivatd scholars who take a Revisionist approach to interpreting Israel's history in dark and conspiratorial tones. Orde Wingate to this group is a moody man, engaging in un-justified violence and whose cruelty worked against Jewish attempts to forge a peaceful place in the Middle-East. Engaging in selective quotations, ignoring documentation and facts which do not suite their agenda, this group has failed to raise any serious debate on the subject of re-interpreting Wingate's contribution.

Orde Wingate as "HaYedid" has not passed from Israeli remembrance and he endures in Israel in other ways. A kibbutz for orphans in his name exists near the town of Haifa. Along the coast there is the national sports complex in Israel in his name. The army military museum has on display his personal pistol and a service cap. Streets in his name are in the larger cities. At Ein Herod the museum displays his bible and photos alongside a reunion trophy from SNS veterans.

Ethiopia

In Ethiopia, Orde Wingate is fondly remembered and viewed as an important figure in modern Ethiopian history. Such was his appreciation that, upon hearing the news of his death Emperor Haile Selassie asked that Wingate's body be interned in Ethiopia. The Emperor sent a gold chain and cross to

Wingate's son,

born six weeks after his father's death. In Ethiopian history today, and in the memory of those Ethiopian veterans of the campaign whose ranks like those in Israel are dwindling, Wingate is "the fighter, the single-minded champion of Ethiopian freedom, the man who brought the Emperor in, a legend then and a legend still today."3 A school for boys in Addis Ababa is named in his memory.

In Ethiopia, Orde Wingate is fondly remembered and viewed as an important figure in modern Ethiopian history. Such was his appreciation that, upon hearing the news of his death Emperor Haile Selassie asked that Wingate's body be interned in Ethiopia. The Emperor sent a gold chain and cross to

Wingate's son,

born six weeks after his father's death. In Ethiopian history today, and in the memory of those Ethiopian veterans of the campaign whose ranks like those in Israel are dwindling, Wingate is "the fighter, the single-minded champion of Ethiopian freedom, the man who brought the Emperor in, a legend then and a legend still today."3 A school for boys in Addis Ababa is named in his memory.

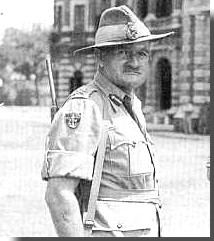

photo caption

General Wavell inspect-

ing Chindits. Wavell was one of several senior figures who backed Wingate, and Wingate owed him much.

Photo courtesy of the

Imperial War Museum, London

Great Britain

It is in the U.K. that the greatest debate over Wingate and his place in the history occurs, one of the most contentious over any British general. The debate revolves around Wingate's personality and method to overcome obstacles to his goals, but also the one of the conventional versus unconventional soldiering. After Churchill rejected Mountbatten's request to censor the news of Wingate's death least there be a drop in morale, an official announcement was made April 1st of 1944. Many notable figures from Churchill to Slim to Wavell gave luminary platitudes to the recently deceased. Journalist and participant accounts in articles and books during and in the immediate aftermath of the war presented Wingate in a favorable light. After the war, the Japanese army commander at Imphal-Kohima said upon hearing the news of Wingate's death, "General Wingate's airborne tactics put a great obstacle in the way of our Imphal plan and were a very important reason for its failure...I realized what a loss this was to the British Army and said a prayer for the soul of this man in whom I had found my match."5

But as a portend, the criticisms and anger that were building up started to come out even before the end of the Imphal-2nd Chindit campaign. Having heard of the opposition Wingate had aroused in official circles, a correspondent wrote how sad it would be if the opposition from the Indian Command to Wingate's Chindits should cause Wingate's ideas to be discarded. He wrote how the Indian Army was opposed to the Burma invasion in 1944, believing that, "the offensive drive based on the Mountbatten and Wingate plans was ill-suited for the prevailing conditions and that it would have been better

to have left matters in the experienced hands of Indian Army authorities."6 This correspondent was told in reply to his column by a government official that it was the opinion of the Secretary of State for War that Wingate was "no longer sane at the time of his death and it was desired that his short-comings should be listed for the record."7

to have left matters in the experienced hands of Indian Army authorities."6 This correspondent was told in reply to his column by a government official that it was the opinion of the Secretary of State for War that Wingate was "no longer sane at the time of his death and it was desired that his short-comings should be listed for the record."7

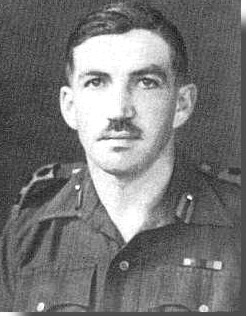

photo caption

General Slim, Burma 14th Army Commander during Chindit II, was one of Britain's best and most successful generals from the war. He served in campaigns from Ethiopia to Vichy Syria to Burma. Postwar he became chief of Britain's army.

Photo courtesy of the

Imperial War Museum, London

One officer whom Wingate clashed with in India was General Woodburn Kirby. As a senior staff officer in the Indian Army command during the 1st Chindit mission, he was the officer in charge for assisting in the equipping and preparation of the force. Kirby opposed the Chindit idea, Wingate's directness, and resented Wavell's favoring the Chindits. During the planning stage of the 2nd Chindit mission he was for a short time the Deputy Chief of Staff. He opposed the breaking up of conventional units to supply men for Operation Thursday, and bitterly resented Wingate's clashing with his staff. And like others he was antagonized by Wingate's disrespectful & at times unfair criticisms of the Indian Army. Appointed to edit the volumes of the official British government story of the war against Japan, he represented many others in which he "took his revenge."8

In the British "Official History of the War Against Japan" Volume II covers the first Chindit mission. And while it contains many criticisms of Wingate personally, it also mentions the long-term affects such as the success of the long-range penetration method and this effect upon the Japanese strategy for 1944. It is in Volume, III which covers the period involving the 2nd Chindit operation that Kirby shows his venom and adverse assessments. Selectively using facts from British and American sources, ignoring some Japanese evidence, listening only to those senior officers who disapproved of Wingate and his ideas, he manages to present an unfair image of Wingate and the Chindit effort. Kirby criticized Wingate's ideas of long-range penetration & allocation of manpower to his force, and statedhis forces were unsoundly used and handled badly in conventional fighting. Wingate, he wrote, lied to others such as Fergusson and Slim, and he hinted that psychologically he might not have been mentally balanced.He claimed looking purely at numbers the Chindits did not accomplish much that other regular forces could not. And in a unique critique of a single individual, the Official History contains a short and negative assessment of Wingate as a commander. Summing him up he wrote, "Wingate had many original and sound ideas. He had the fanaticism and drive to persuade others that they should be carried out, but he had neither the knowledge, stability nor balance, to make a great commander."11

Field Marshall Slim's views on Wingate altered after the war, in contrast to his appreciative words spoken during the Burma campaign and right after his death. In his biography of his wartime experiences, Slim like the Official History authors also wrote that Wingate's obsession over his force was due to his own personal ambition. Echoing future writers, he stated Wingate was a difficult and often insubordinate subordinate who selfishly believed that the Chindits were the sole means for defeating the Japanese. Slim also exaggerated the debate on March 5th 1944 when it was discovered that Piccadilly was blocked. Putting him in a poor light, he wrongly stated Wingate panicked and turned to Slim for assistance. This has been contradicted by everyone else who was present. Slim put down Wingate's ideas and the achievements of the Chindits, believing the creation of a 'private special forces' to be wasteful in terms of men and results achieved. He believed forces used in a more conventional manner were best, writing, "We are always inclined in the British Army to devise private armies and scratch forces for jobs which our ordinary formations with proper training could do and do better."12 Much of the writing on the Burma campaign for the first couple decades after the end of the war would turn to the writings of Kirby and Slim, and thus incomplete assessments of Wingate would be and often still are repeated by other writers.

One situation that Wingate's critics have attacked him on is the medical state and casualties of the Chindits. This is correct for the first campaign in terms of food supply and the seeming fatalistic attitude towards catching malaria. But this ignores the fact the heavy casualties in the 2nd campaign were a result of the use of the Chindits being miss-used. In contrast, both the Indian and US government official histories provide more balanced assessments and recognize the Chindit accomplishments and the unfulfilled potential. Another criticism is his handling of Bernard Fergusson's brigade in the 2nd Chindit operation. Before his failed attack on Indaw, Fergusson was under the impression that Wingate was planning to get another brigade (14th) into action to assist his columns. This did not happen and Fergusson, not knowing this, for years criticized Wingate's attention to the truth. This was picked up by Kirby who attacked Wingate for deceiving Fergusson. The moving of Chindit Headquarters from Imphal further west due to the Japanese advance meant Fergusson was out of radio contact with Force HQ for several days. During this time Wingate changed his plans, thus the mix-up. The use of 14th Brigade has also been misinterpreted to incorrectly stating it was deployed in disobedience to Slim's agreed upon plans.

photo caption

Brigadier-General Michael Calvert right after the war. After action with the Chindits, Calvert led the SAS (Special Air Service) towards the end of the war in Europe. He would go on to help reconstitute the SAS during the Malayan War. His postwar career ended prematurely due to his association with Wingate & personal problems.

Photo courtesy of the

Imperial War Museum, London

photo caption

Wingate with his chief-of-staff Derek Tulloch during Chindit 2 in 1944. Tulloch fought for his friend's reputation long after the war.

Photo courtesy of the

Imperial War Museum, London

photo caption

Wingate with his aide after returning across the Chindwin River after the Chindit I mission of 1943.

Photo courtesy of the

Imperial War Museum, London

Another view of Wingate is of an over-rated, inexperienced commander who was able to flourish due simply to high-level patronage. After the war Michael Calvert discovered the writings from a meeting of the Army Council that was debating the future policy towards presenting Wingate and the Chindits. Over the objections of the Air Force representatives, it was decided it was best for the British Army to write down the achievements of the Chindits, "it was in effect 'We know these units fought very bravely and successfully and the Japanese have a very high opinion of them and of the decisive results that they achieved. But Wingate was a divisive influence on the British Army & we do not want every company commander thinking he is a Wingate. We don't want any more Wingates in the British Army. Therefore we must write down the Chindits."13 While revising the Special Air Service (SAS) for the Malayan War, Calvert also discovered the Chindit experience was being disregarded and Burma was deliberately ignored. In spite of the respect held by his Italian and Japanese, this official attitude continued down after the war. Instead, inside the British military staff colleges through the 1960's the negative image of Wingate was taught.

Eventually these adverse words motivated many Chindit veterans and other authors to rush to Wingate's defense.

Derek Tulloch

who served as Wingate's chief of staff spent much of his life after the war writing a book to try to set the record straight. He relied upon many of Wingate's private papers and official orders and signals during the 2nd Chindit campaign that he had secretly kept.

Unable to persuade the official military establishment to revise their assessment of Wingate, he took matters into his own hand. In spite of threats of court-martial, he published a book on the Chindit campaign and in defense of his

long-time friend.

He died soon afterward. Others who had served under and worked with Wingate picked up the struggle.

Unable to persuade the official military establishment to revise their assessment of Wingate, he took matters into his own hand. In spite of threats of court-martial, he published a book on the Chindit campaign and in defense of his

long-time friend.

He died soon afterward. Others who had served under and worked with Wingate picked up the struggle.

A staff officer for air operations and the senior RAF advisor to Wingate during the 1944 campaign, Brigadier Peter Mead and Sir Robert Thompson respectively, responded to the discrediting. Presenting their evidence they wrote to the British Cabinet Office of History to unsuccessfully ask them to amend the official military histories written. Both wrote their own impassioned stories of the Chindits and Wingate. Thompson wrote that the criticisms over the idea of the Chindits used behind enemy lines instead of fighting a more conventional battle at Imphal was shortsighted. He summed it up by writing, "It is necessary to think of the consequences if, two days after the D-Day landings in Normandy in 1944, two German airborne divisions had landed in central southern England and blocked several of the main roads leading to the south coast ports."15 He goes on to say that the official assessment of Wingate is "no more than a hatchet job by little men who could not have competed with Wingate either in military argument or in battle."16

Most Chindit veterans have written favorably about their former commander. Bernard Fergusson's admiration for Wingate's ideas and the confidence he was able to create in others, remained in spite of conflicting feelings over the years about his character and conduct. Writing prolifically about the Burma campaign, Fergusson in his books like Calvert generally respects Wingate for his military prowess, inspiration, and resoluteness. In his writings he was willing to include his critique of Wingate's strength and weaknesses. Writing of Wingate's tough training standards being necessary to wield an effective force against a tough enemy, he wrote, "Wingate may have appeared as an ogre, and was a fearsome man to cross, but he had only one standard - perfection. He seemed to almost rejoice in making enemies, but he was a military genius of a grandeur and stature seen not more than once or twice a century."17 To Fergusson, those that put down Wingate reminded him of, "The mouse which takes a swig of whiskey and says 'Now show me that damned cat.'"18

photo caption

Part of the small exhibit

dedicated to Wingate at the Ein Herod Museum, Kibbutz Ein Herod in Israel.

Personal photo

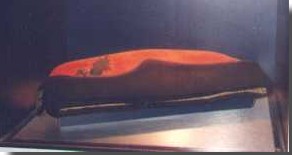

photo caption

Wingate's field service

cap on display at the Haganah Museum,

Tel Aviv, Israel.

Personal photo

photo caption

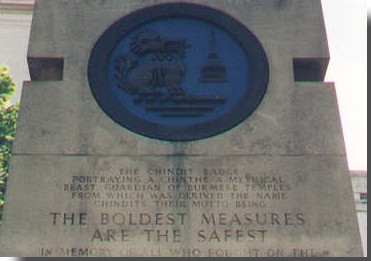

The Chindit Memorial in London, England.

Personal photo

photo caption

One of the top inscript-

ions on the Chindit Memorial in London, England.

Personal photo

Last Battle

Many who have come into contact and fought with Orde Wingate starting from his time in Palestine recognized the deep impact this man who "sincerely thought of himself as the instrument of fate"19 had upon them. Recognizing his leadership, they have reflected upon the impact of his personality and ideas. One SNS veteran wrote, "He seems also to have a personal magnetism, causing men to follow him without knowing why...He had a magnetic personal manner and spirit, but that was not enough. He also knew his job!"20 Rex King-Clark was a junior officer who served with him at the time, and confirmed this impression saying, "I personally consider it a high privilege to have served under Wingate's inspiring leadership...Mike Calvert said of Wingate that he drew the best from his subordinates. Such as it was, he drew the best from me."21

His intelligence and determination to achieve success was also noted from those who fought with him in Ethiopia. As Wilfred Thesiger, one participant of Gideon Force put it afterward, "In my opinion, no other officer in Platt's or Cunningham's army could have achieved what Wingate did, with the force at his disposal."22 Wrote one soldier who had fought in Ethiopia during the war confirming this from afar long afterward, "Wingate was a brilliant innovator, had great strategic insight, and had the power to inspire and lead first-class subordinates and to make them trust and believe in him."23

Participants of Wingate's Chindit expeditions have generally lauded Wingate's abilities and his ideas, recognizing Wingate was ahead of much of contemporary thinking. A leading participant in both Chindit expeditions, Mike Calvert wrote, "He was not only a fine leader, but a good kindly, generous hearted man, who felt the rebuffs of his trade more than most people realized. He left us richer in faith, strength of purpose and in ideas for the future, as well as in military knowledge."25 Wingate's principal RAF air liaison officer Robert Thompson agreed, saying "The two qualities that made him stand out higher than most of his contemporaries were his vision and his determination. It was these, aided by his intellect and advocacy, that made the impact on the great men of his time who supported him. It was these qualities too that upset many of his lesser contemporaries."26

The theories and operations of modern militaries are the result of experiences gained from past experiences of warfare, and lessons from their study. The campaigns Wingate took part in are no exception to such contributions. His military thinking and experiences has helped to influence and highlight modern military doctrine today, and his thinking is apparent in the evolution of his tactics and strategy. Starting from the counter-insurgency tactics he used in Palestine through the long-range penetration force in Ethiopia one sees a linear progression of deliberate thought and doctrine which would evolve and reach its zenith during his days fighting in Burma. As an unconventional fighter, "There may be those who think of Wingate as a swashbuckler and a dare devil. He was neither of these. He took risks, great risks, but studied risk."28

In Israel Wingate's Special Night Squads helped to teach many future leaders their foundations of future success. Wingate stressed the importance of the unconventional response to an unconventional challenge which, if well-led and trained, could lead to a self-reliant and successful unit. Emphasizing the results of boldness, initiative and surprise, he showcased what good, intelligent small-unit leadership and tactics could achieve in a counter-insurgency campaign, "a seminal event in the theory of counter-insurgency."29 Which by necessity is a war that demands emphasis on determined small units & the need for intelligence and aggression.

The actions of Gideon Force in Ethiopia are an example of a force multiplier and complimentary threat accompanying main regular forces, a classic role for a unit operating in guerilla warfare style. Wingate created a deep penetrating, mobile force to fight, exploiting the political conditions to be able to be self-sufficient and gain intelligence. He believed this would give the insurgents the shock force to win their campaign, instead of only relying upon guerilla warfare. As Captain W. E. D. Allen who served as animal transport officer in Gideon Force put it, "The guerilla campaign in the Gojjam had presented an example of the effectiveness of a small disciplined force acting as a spearhead to pries open an interior front in enemy territory where the population was hostile to the occupying power. The guerilla operations - which could not have been decisive in themselves - had been co-ordinated with regular operations on major fronts and had, by promoting a process of disintegration in the rear of the main Italian armies, contributed to a remarkably rapid decision."30

With the Chindit expeditions in Burma Wingate was ahead of much of the contemporary thinking in the use of airpower for supply and close-air support for a large force operating for an indefinite time behind the enemy's lines in an offensive manner. Self-contained ground and air units operating together behind enemy lines, in conjunction with a main force, would threaten and strike key targets at key times so as to be a mortal threat to the enemy. And they would gain the element of surprise and the initiative. This required a vision, an organization to carry it out, and an effort to put these into action. The use of regular forces behind enemy lines, being directed by radio, supplied and aided by air, had all been done before. It was Wingate's Chindit expeditions that put these all together and on a large, permanent scale. Michael Calvert who fought who Wingate in both Chindit campaigns wrote on the war in Burma and was perhaps most closest in agreeing with Wingate's ideas. He has tried to sum up Wingate's proper place in the Burma Campaign writing, "By his personal endeavors and brilliant original thought he had transformed this theatre of operations from a slow-moving, archaic grappling in the darkness of the jungle to the most forward-thinking of all battle fronts of the world, using air and area warfare in a way and on a scale never employed before and which has completely revolutionized military thought & operations ever since."31

Today the Special Forces community on both sides of the Atlantic as well as the military in Israel understands Wingate's accomplishments and respect his foresight of ideas which have made what was uncommon then common today. In contrast to many in the regular armies, both the U.S. and British air forces have always recognized the leadership of Wingate, seeing the potency of the combination of air with ground forces operating the way they did. Many conventional military men and authors view the fact since the major fighting in 1944 and 1945 was done by the conventional forces of British, Indian, and African units that both Chindit efforts were but a sideshow and a costly diversion of effort. But it was the Chindit operations & their repercussions which set the stage for the successful strategy and fighting of the future in Burma. Part of the problem for many has to do with the lack of understanding of the indirect affect Wingate's effort had upon the outcome of the war in Burma.

The evolution of Wingate's military ideas and his campaigns also highlight the long-standing debate between conventional forces with their need for common tactics, training and discipline. And those of unique units with different leadership & tactics that are needed for unconventional and unique missions. Orde Wingate will continue to be studied and debated.

1. Moshe Dayan, Moshe Dayan: Story of My Life (New York: William Morrow & Co., 1976), 46.

2. Yosef Eshkol, A Common Soldier (Tel Aviv: Israeli Ministry of Defense, 1993), 202-03.

3. David Shirreff, Barefeet and Bandoliers (London: Radcliffe Press, 1995), 221.

4. Field Marshall Earl Wavell, Soldiers and Soldiering (London: Jonathan Cape, 1953), 107.

5. Tulloch, Wingate in War and Peace (London: History Book Club, 1972), 265.

6. Peter Mead, Orde Wingate and the Historians (Devon: Merlin Books, 1987), 142.

7. Mead, 142.

8. Shelford Bidwell, The Chindit War (New York: MacMillian Publishing, 1979), 40.

9. Trevor Royle, Orde Wingate, Irregular Soldier (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1995), 321.

10. Tulloch, 263.

11. David Rooney, "A Grave Injustice: Wingate and the Establishment," History Today, Vol.44 (March, 1994): 12.

12. Royle, 323.

13. Tulloch, 269.

14. Ibid, 131.

15. Sir Robert Thompson, Make For The Hills (London: Leo Cooper, 1989), 76.

16. Thompson, 73.

17. Bernard Fergusson, The Wild Green Earth (London: Collins Publishing, 1946), 241.

18. Bernard Fergusson quoted in Rooney, 12.

19. Christopher Sykes, Orde Wingate (New York: World Publising Company, 1959), 539.

20. Major Haye quoted in Israel Defense Forces, Haganah Museum doc.143-12.

21. Rex King-Clark, Free For A Blast (London: Greenville, 1988), 204.

22. Wilfred Thesiger, The Life of My Choice (London: Collins, 1987), 353.

23. Shirreff, 222.

24. Royle, 11.

25. Wilfred Burchett, Wingate's Phantom Army (London: Frederick Mueller, 1946), 5-6.

26. Thompson, 71.

27. Royle, 68.

28. Mead, 130.

29. Bidwell, 44.

30. W.E.D. Allen, Guerilla War in Abyssinia (London: Penguin, 1943), 125.

31. Mead, 134.

32. Sykes, 543.